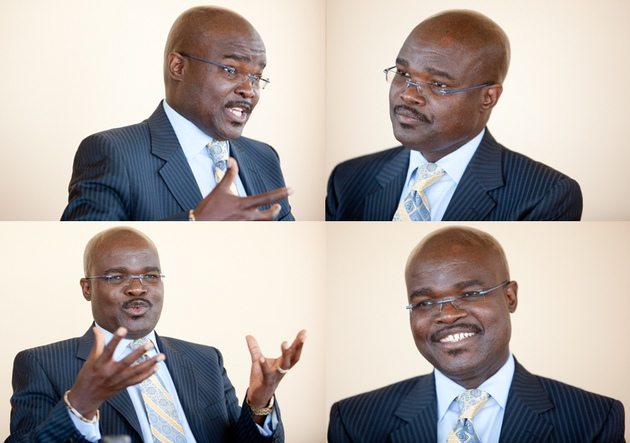

Paul Zeleza is dean of the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts at LMU. He has taught at universities in Canada, Jamaica, Kenya and the United States. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Malawi, a master’s degree from the University of London and a Ph.D. from Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada. Zeleza is the author of “Barack Obama and African Disasporas: Dialaogues and Dissensions,” published by Ayebia Clarke Publishing in London. He was interviewed by LMU Magazine Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch.

In your book “Barack Obama and African Diasporas,” you write essays as a public intellectual on a range of subjects. Is it difficult to balance the life of an academic with the role of a public intellectual?

For me, it has not been difficult because I have always tried to do both from the very beginning. When I went to university in the ’70s in Malawi, we were trained to become not only academics but also intellectuals who deal with fundamental questions facing society. That’s what I’ve always tried to do.

You lived in self-imposed exile for 17 years while Malawi, your home country, was under a military dictatorship. Are there lessons from your experience that you impart to your students?

One is that we have the capacity to survive very difficult situations. Facing difficult situations sometimes brings out our possibilities. So we should not be afraid of challenges and difficulties. We should use challenges, whether they are personal, political or social, as a means to empower ourselves in order to transcend those challenges.

Challenges such as yours seem limiting and restrictive. How are they empowering?

They are empowering because you have to dig deeply into yourself to find out what really matters to you, what is important, what is valuable and what your ideals are. You must decide what kind of person you want to be and what kind of contributions you want to make to society. Facing them puts things into perspective.

It is said in the United States that President Obama is more concerned with Africa than previous U.S. presidents. As an African, do you agree with that?

Yes and no. Yes, he is concerned at a personal level. Kenya, his father’s birthplace, is extremely important for him, and, of course, he has visited Africa several times. No, in the sense that as president, he represents U.S. governmental policy. It is too soon for us to tell whether he is going to be better or worse for Africa.

You sometimes refer to an African saying: “I am because we are.” What does that mean?

As human beings, we are individuals precisely because we are members of society. We are never by ourselves; whatever happens to us happens in a context. In a lot of African communities, a communitarian sense of belonging — that society owes every member of society their well-being — is very powerful. If one person is suffering, then the entire society is not whole. I think there are a lot of connections to the Jesuit notion of an individual being responsible for himself but also for others.

How do you describe Africa’s influence on the United States?

The cultural impact is massive: music, arts, dance, poetry and fiction. Economically, the foundation of the America owes a lot to African labor. Today, the United States is Africa’s largest trading partner. In politics, the struggles for emancipation from slavery up to the Civil Rights movement, and contemporary struggles, have been central to the expansion of American notions of democracy and human rights.

In the future, Africa’s oil will continue to be crucial to the United States, because the oil in West Africa is relatively close, geopolitically speaking. Also, the people-to-people connections will intensify. And the election of President Obama is making Africa more present in the American imagination than it has been before.

If Americans want to begin understanding Africa, what is the first book they should read?

They should read “Things Fall Apart,” by Chinua Achebe, a book that is a beautiful story about the encounter that has defined Africa for the last hundred years or so. Achebe’s novel is about the encounter between Africa and Europe through colonization and the impact it had on Nigerian society, which is emblematic of the impact on African societies.