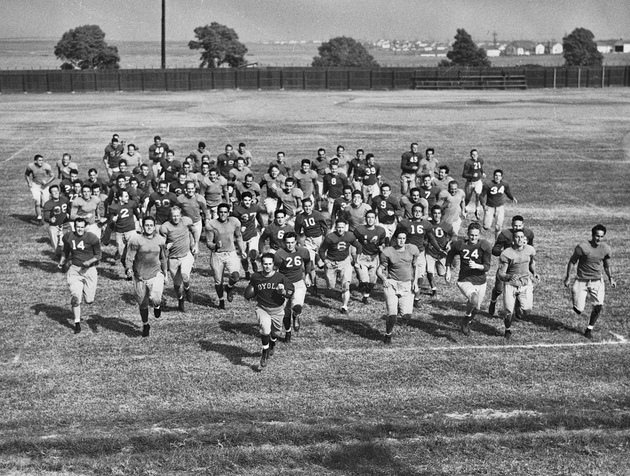

The story of the 1950 Loyola football team is about much more than wins (there were eight) and losses (only one). At the time, the team was nationally ranked, even higher than future powerhouses USC and UCLA. No fewer than nine of its players went on to pro careers. That the football program would be canceled after only one more season turns that 1950 team into a shooting star in the history of Loyola athletics.

But perhaps the most significant event of the 1950 Loyola football season involves a game that the team did not play. And the reason the game was not to be — based on a simple, steadfast belief in right and wrong — is a testament to enduring values that have guided Loyola Marymount University in the ensuing decades.

SEPARATE ACCOMMODATIONS?

It started with an exchange of typed letters. Making preparations to travel to El Paso to play Texas Western College (now the University of Texas, El Paso) on Sept. 30, 1950, Loyola team manager Red Hopkins wrote: “This is to verify reservations for approximately 52 people. Would you kindly answer one question? We have a colored trainer and possibly three colored players on the team. What is your policy on this matter?”

The Texas reply is not available, but Hopkins’ next letter picks up the thread. “Could you make arrangements for them to stay with a colored family in El Paso? However, they will be eating with the team at Cortes Hotel.”

On Sept. 23, just a week before kick-off, arrangements were confirmed to accommodate the black members of the Loyola contingent, including halfback Bill English and trainer Oscar Cunningham, at the home of Mrs. Collins, “who happens to be our housekeeper,” wrote Rev. Msgr. G.W. Caffery of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in El Paso.

But a greater obstacle had not been overcome. The Board of Regents of the University of Texas, of which Texas Western was a member, would not budge from its longstanding rule that blacks could not play for or against football teams in its division.

The next letter from Hopkins was brief: “Please cancel our reservations this weekend. Thanks.”

Not much else is available on the record about the discussions that would lead to Loyola’s decision to cancel the game if all its team members and staff were not welcome. The ultimate decision rested on the shoulders of Charles S. Casassa, S.J., president of Loyola. His official statement, released Sept. 28, 1950, was: “The decision was regretfully reached because of certain player restrictions which would have been in force were the game to be played.”

Chuck Hovorka ’49, an ardent supporter of the team, was a student of Casassa at Santa Clara University before they both came to Loyola. They were close, and Hovorka recalls talking with him days after the decision to cancel the game: “He was very firm. He said, ‘I know in my mind I did the right thing as a priest and the right thing if I hadn’t been a priest.’ I remember that very clearly.”

The financial loss stemming from the cancellation was estimated at between $5,000 to $10,000. Public reaction was overwhelmingly positive. Even the El Paso daily newspaper lamented the outdated rule.

“They felt that they were not being evaluated at all for their skill in playing ball; they were being evaluated for their race,” Horn says.

For the Loyola players, many of whom have passed away, the decision was unanimously supported. “It was a question of integrity and being responsible for what you believed in,” says Fred Snyder ’52, a wide receiver. Snyder recalls Coach Jordan Olivar telling the team that “if their fans didn’t want to see any black players, they wouldn’t see any black players and they wouldn’t see any game.”

Vernon Horn ’58, an African American running back, was also on the team. He arrived from Iowa shortly after the cancellation. Although a freshman, he had been tagged a future pillar of the backfield, and he appears in the 1950 yearbook varsity team photo. (In less than a year, Horn was drafted into military service. He returned afterward, completing his bachelor’s degree in 1958.)

Horn roomed with English, and the two of them talked with Cunningham and sophomore Clarence Lofton, another African American player, about the incident. “Bill was extremely upset and frustrated with that situation,” Horn recalls.

JACKIE ROBINSON’S EXAMPLE

The African American players, Horn says, were angry. As members of the team, they felt completely accepted by the other players, and they also knew they were important contributors to the team’s success. But because of discrimination, they were prevented from performing together as a team. “They felt that they were not being evaluated at all for their skill in playing ball; they were being evaluated for their race,” Horn says. It was only a few years before, in 1947, Horn recalls, that Jackie Robinson became the first black player in Major League Baseball, and Robinson’s example as a Brooklyn Dodger was on his mind and the mind of many black athletes.

The players recognized the significance of the decision at the time. “It was an era of Jim Crow, and those were the conditions that prevailed,” says Dick Nanry ’51, a lineman on the team. “But the university took the correct stand; we wouldn’t be making that trip without our fellows. Today, you can’t even imagine the necessity for that arising.”

As competitors, the players and coaches were understandably disappointed to not play the game. But they quickly turned their focus to the next game on the schedule, crushing Saint Mary’s College 48–0. The team would go 7–0 before losing to Santa Clara 28–26 in the second to last game of the season. That loss probably cost Loyola an invitation to the Orange Bowl, even though the team ended the season beating ranked University of San Francisco.

Nanry notes that only a few years earlier, the Loyola team was led by black co-head coach Al Duval ’36, a former Lion player as well. “He might have been the first black coach at a major program,” Nanry says. “Imagine if Texas Western had said to leave the coach behind.”

Sixty years later, many of the key figures of the memorable season are gone, but not forgotten.

Coach Olivar, widely considered the creator of the most innovative passing offense of his time, died in 1990. He left Loyola to coach Yale from 1952–62. His 1960 team earned the Lambert Trophy as the best in the East. His death was noted in the New York Times and, at his request, Olivar’s ashes were scattered at the top of the Palisades.

Oscar Cunningham was an athletic trainer for Paul Brown’s Cleveland Browns and a talent scout for the Browns, the Houston Oilers and the Canadian Football League, as well as baseball’s Los Angeles Angels. He passed away in 1984.

Don Klosterman ’52, “The Duke of Del Rey,” died in 2000 after a distinguished career as an NFL executive. Well after his playing days, he remained close friends with Cunningham, who had taken Klosterman under his wing when the latter was a boy growing up in Compton.

“It was a question of integrity and being responsible for what you believed in,” says Fred Snyder ’52, a wide receiver.

‘WE KNEW WHAT A TEAM WAS’

Some of the remaining members of the 1950 team still get together twice a year. Harry “Skip” Giancanelli ’51, who played four years for the Philadelphia Eagles, has a scrapbook his late wife kept of the Loyola years. “I don’t think there’s ever going to be a team like the ’50 team. The air around Loyola was unbelievable. The campus was alive. With the student body there now, it would have been incredible. I went to my wife’s grave the other day, and I thanked her for all those memories she saved.”

Horn, too, remembers the 1950 team as an extremely close-knit group. The African American players felt that Loyola stood up for them, and they appreciated it, he says. “We knew what a team was. We didn’t want in any way to distort that or have anybody try to rip that apart. We were accepted by everyone. We liked all of our players, and they liked us.”

Giancanelli agrees. “We remain close all these years,” he says. “We had the same values. We really cared for one another. That closeness as individuals made us a great team.”

Aaron Smith is a Los Angeles-based writer and contributor to LMU Magazine. This article was published in the summer 2010 issue (Vol. 1, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.