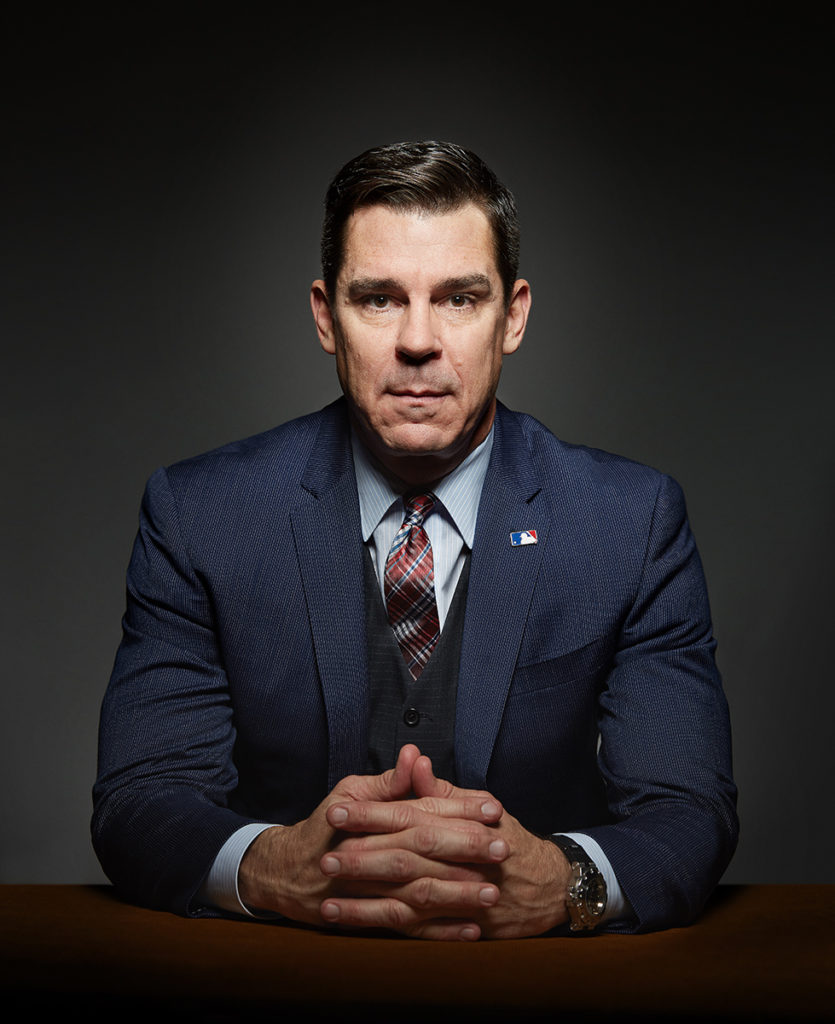

In July 2014, a year after prohibiting baseball players from harassing and discriminating against other players on the basis of sexual orientation, Major League Baseball named Billy Bean ’86 its ambassador for inclusion. Bean’s role is to fight prejudice with talk, meeting with players, coaches, general managers and owners to share his story of playing big league baseball while protecting a secret. Bean spoke about his work at MLB and his career with Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch. Bean also discussed his career path from LMU to MLB and his decision to come out in a video interview with LMU Magazine.

How did your assignment as Major League Baseball’s Ambassador for Inclusion come about?

I was out of baseball for quite a while. I had evolved tremendously off the field, but I didn’t think there was a place for someone like me, who was gay and out, in baseball. The first meeting with MLB wasn’t to offer me a job but more of a consultant position. They thought there would be a couple of events throughout the year when it would be important to share my story. We were scheduled to talk for an hour, and the meeting went for three or four hours. Three or four days later, they asked if I would consider working with them.

How do you approach people or players who you know may disagree strongly with you?

I talk about the fact that, regardless of differences between us, we have shared values about baseball: respect for our sport and the responsibility that goes with being a player. It’s interesting: Few people understand what it’s like to be the only gay person in a room — especially one with a bunch of young male, millionaire athletes — and to talk about your private life. But for the first time, players are discussing these issues with a former player. For that, I give MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred great credit. He said over and over: It’s different when a peer or a colleague is sharing a message.

Does MLB’s work on this issue involve the public, through things like Pride Night, as much as it does players and team organizations?

Absolutely. Pride Nights aren’t intended to invite specifically the LGBT community; [rather] the events send a message that they are welcome as well. For example, the Boston Red Sox hosted a Pride Night on June 3. It’s not a [business] decision. They don’t need to do that to add fans: They sell out [almost] every home game. They have Pride Night because they realize it’s an important message.

Do you think things are getting better in terms of society in general?

Things are getting better, but you still see instances where states are creating legislation to legalize discrimination against the LGBT community. My job is challenging in many ways, but it’s rewarding because I feel I am here to make a difference in the positive direction.

Looking back on your career, what did you learn or experience as a player that has been the most useful lesson to you now?

I think everything about my playing career helps me each and every day. For one thing, it gives me the guts to walk into a clubhouse, a pressroom or a meeting of owners, and feel that they will respect me. One of the great lessons I’ve learned is that I never gave myself much credit as a player. Even if I had been a great player, I may have a chance to have a bigger impact at the job I’m doing now.

Your jersey, No. 44, was retired by LMU in march 2000. How did you feel about that then?

It changed my life. I thought because I was gay that my own school would not want my name on any wall. It was a very emotional moment. A few years later, Lane Bove, senior vice president for Student Affairs, invited me to lunch and showed me the LGBT Student Services office on campus, and that was incredible. The generosity in allowing kids to be who and what they are enables them to live a healthier and better life. Many of us, unfortunately, haven’t been in the time and place to be our best self yet, and that is a gift I would love to give everybody if I could.

You were one of the best hitters in LMU history. Does hitting come naturally or can it be taught?

I don’t think you can teach someone how to hit a baseball. You can teach someone how to hit a baseball better. There is a degree of talent that you cannot teach. Whether someone cultivates that or throws it away is the question.

Do you ever think that, because of your own experience, you have a better idea of what Jackie Robinson went throughout?

I think about Jackie Robinson just about every day. His life experience and his legacy are part of the reason why the expectations of baseball are so high in terms of social responsibility.

Billy Bean, a prolific left-handed hitter who set several LMU records, led the 1986 LMU baseball team to the College World Series. He was named a second-team All-American in his senior season. Bean entered the LMU Athletics Hall of Fame in 2000 and was inducted into the WCC Hall of Honor in 2012. Drafted in 1986 by the Detroit Tigers, he tied a major league record in April 1987 by getting four hits in his first appearance. Bean went on to play for six seasons with the Tigers, the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Diego Padres. After his career ended, Bean came out as gay in 1999, and he later wrote “Going the Other Way: Lessons From a Life In and Out of Major League Baseball.”