Googling oneself is an exercise of quiet narcissism that many of us indulge in, I suspect.

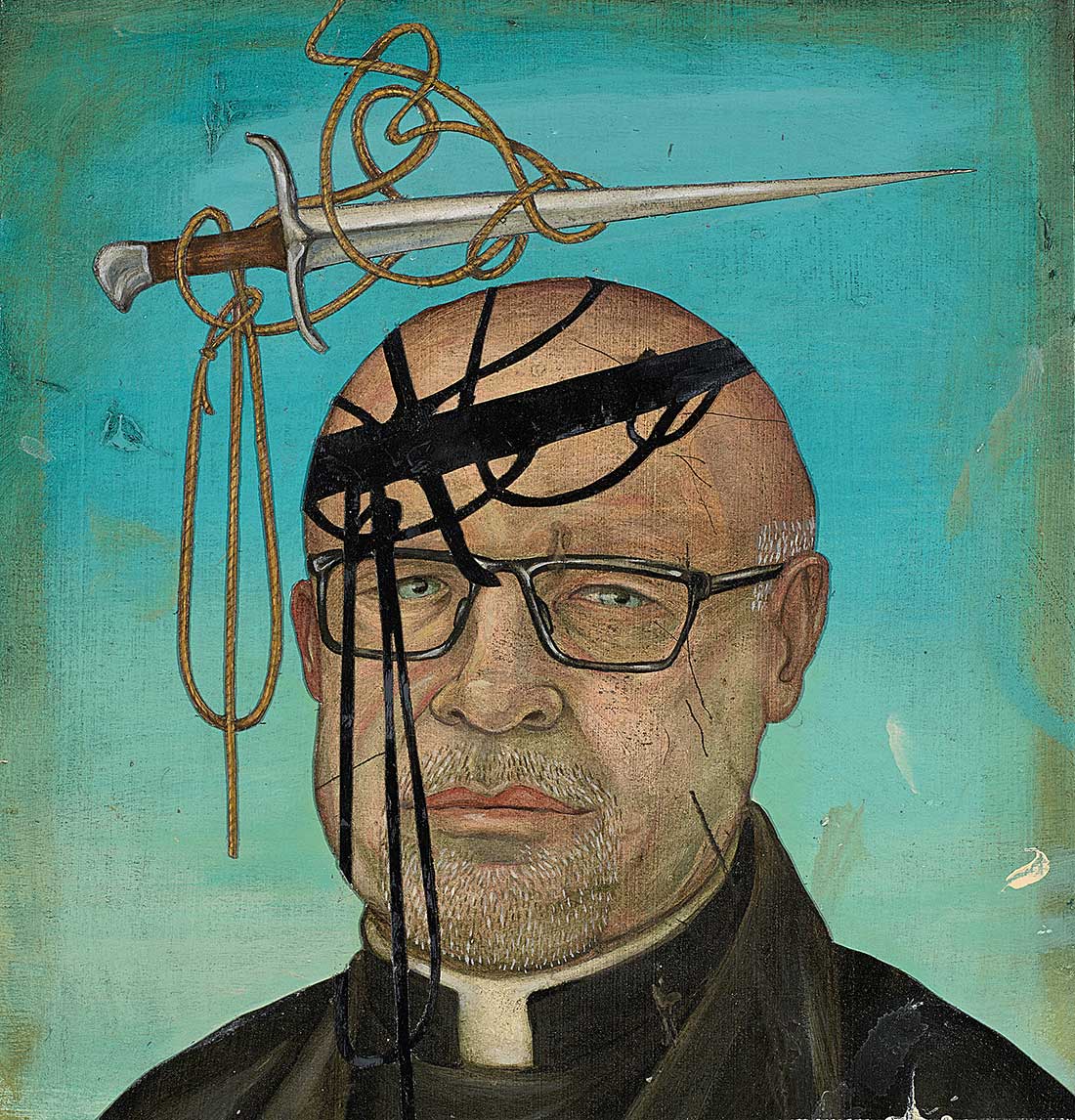

Google “Welsh Jesuit” — something I do occasionally — and there appears an engraving of a man with gaunt features and an enigmatic expression. Less ambiguous is the rope around his neck and the large knife sticking out of his chest. The inscription describes him as “Priest of the Society of Jesus, Charles Baker Lewis.”

David Lewis, born in Wales in 1616, took “Charles Baker” as only one of several pseudonyms over the course of a necessarily hidden life. Raised a Protestant, Lewis became a Catholic while living in Paris. He entered the Jesuit novitiate in Rome and returned to Wales a few years later. His was a peripatetic and life-threatening existence: Being a Catholic priest and celebrating Mass were acts of treason. In 1678, during a wave of anti-Catholic hysteria, Lewis was arrested. A year later, he was executed. Indigenous Welsh Catholicism effectively died along with Lewis. No more Welshmen became Jesuits until 2001, when I entered the California novitiate in Culver City, Calif.

Being the first Welsh Jesuit for more than 300 years was initially a source of pride. I saw something of myself in Lewis: I, too, have lived in several European countries, embraced Catholicism as an adult and entered the Jesuits as an ordained priest. But as I learned more, that connection became discomforting.

In the police state of Tudor and Stuart Wales, religious faith was political. The Welsh Jesuits, never more than a handful, sustained a network of clandestine Catholics who could practice and pass on their faith to their children only illegally and under threat of persecution. Only the brave or rash stood up and stood out. Periods of quiet religious freedom were punctuated by savage persecutions.

Lewis was in charge of an underground seminary, located in a remote rural area bordering England, that trained Welsh Jesuits. His pastoral solicitude earned him the epithet tad y tlodion — priest of the poor. Yet his gentleness did not save him. His engraving’s rope and dagger are polite visual shorthand. At his execution, his chest and belly were cut open and his entrails torn out. Fortunately, a sympathetic crowd had prevailed on the hangman to first let Lewis hang until he died, rather than undergo the vivisection that most of the seven other Jesuit martyrs of 1678–79 suffered.

Academic research is always, at least in part, an exercise in autobiography. As an immigrant to the United States and a member of an ethnic minority, I’ve often described myself, sometimes ironically, as one of the more diverse members of the LMU community. My mother tongue, Welsh, along with its culture, is listed by UNESCO as “endangered.” Just 5 percent of the population of Wales (some 150,000 souls) is Catholic, and, of those, Welsh-speakers number a tiny proportion. There are some six Catholic priests fluent in Welsh, myself among them. Not surprisingly, my scholarly work as a theologian focuses on the fusions and dissonances between religious and cultural identities.

As the only Welsh Jesuit, and now a U.S. citizen, what is “my take” on the life and death of my predecessor? First, like cultural identity, religious freedom is fragile and precious — something the Jesuit martyrs of El Salvador, murdered in November 1989, were witnesses to in our time. I value the separation of Church and State that should preclude wars of religion. But I also wonder if our comparative tolerance witnesses to a faith that is more privatized and indifferent to its wider implications. Lewis’ rope and dagger offer me a challenging suggestion: that our willingness to live our commitments is measured by our readiness also to die for them.

Dorian Llywelyn, S.J., is associate professor in the Department of Theological Studies in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts.

This article appeared in the summer 2014 issue (Vol. 4, No. 2) issue of LMU Magazine.