Where was the anger on the left — the kind that was routine in Europe and South America — after the economic crash of 2008? An important book — “The Age of Acquiescence,” by labor historian Steve Fraser — contrasted the silence among 21st century progressives and working people to the rage among the 1890s Populists. Was Occupy Wall Street all we’d get?

And publications on the right have raged about their side’s complacent responses to the various outrages of Democratic regimes. Not long ago, establishment conservatives saw their role as waking the populace from slumber. “Where’s the outrage?” then-Sen. Bob Dole asked one day in 1996, frustrated over the lack of its anger at the purportedly heinous Clintons. Even Bill Clinton’s sexual improprieties and ensuing impeachment didn’t get Americans terribly riled up — he left office with sky-high approval ratings.

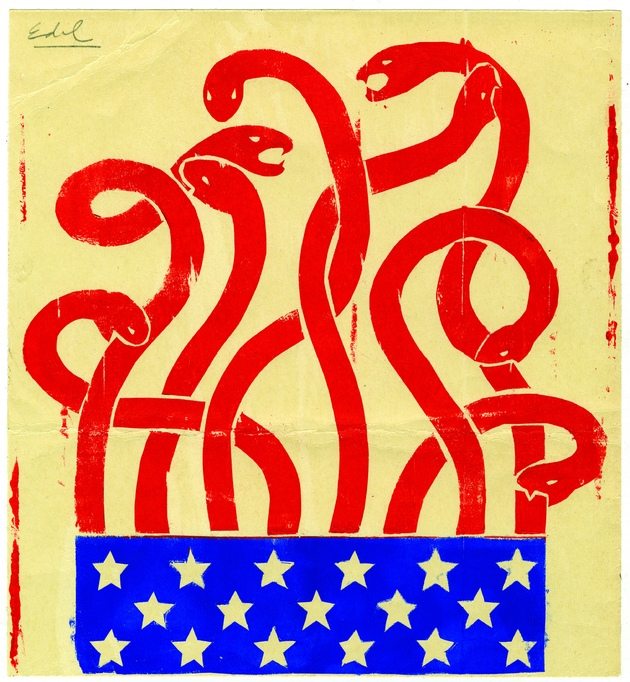

Well, it would be much harder to find someone who thinks that Americans are too easy-going these days. Apathy and moderation have been replaced by rage — on both sides. After the election of Donald J. Trump — who ran on voters’ anger, distrust and sense of betrayal — to the presidency, a newly emboldened far right is flying Confederate flags and painting swastikas on schools.

“You see people making comparisons between black anger and white anger,” says Drummond. “But to me, there’s no comparison. People in Black Lives Matter are angry. But it’s protest toward a goal — a notion of equality.”

Some liberals and progressives are raging about a president-elect they freely call a fascist. Establishment Democrats, followers of Hillary Clinton mostly, and the progressive wing — who preferred Sen. Bernie Sanders and Jill Stein, the Green Party’s nominee — are tearing each other apart on social media. Urban centers, including Los Angeles, are seeing left-of-center marches and protests against the incoming administration and its enlisting of “alt-right” lieutenants (who are themselves driven by rage.)

And the past few years have seen the rise of a kind of African American political activism, built largely on anger and despair, that’s most visible in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement.

So what the heck happened? And where does this kind of political rage lead?

It may just be that the U.S. — despite a longstanding sense of American exceptionalism — is becoming more like the rest of the world. “What I have observed, in many different troubled part of the world, is that political anger is often fueled by dispossession,” says Jok Madut Jok, a professor of history in the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts and native of South Sudan. Jok has witnessed some of the worst extremes of political violence in the civil wars that have beset his country for decades. “By people feeling marginalized and locked out of power and resources and protection. And there are politicians who capitalize on their sense of exclusion.”

In the U.S., says Sean Dempsey, S.J., who also is a professor in the BCLA Department of History, anger doesn’t always come simply from the dispossessed. The early 20th century, he says, saw the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan — middle-class Southern whites who hated not just blacks but Catholics, Jews, and immigrants and saw themselves as an oppressed minority. “That’s an anger not coming from the margins,” Dempsey says. “It’s status anxiety. That’s often where the right-populist anger comes from — threatened privilege.”

Sometimes, of course, anger dissipates. But we don’t have to look far back in history to see cases where rage and dissolution led to significant and, in some cases, frightening change. Professor Elizabeth Drummond teaches modern European history, specializing in Germany and Poland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. She’s wary of glib comparisons between the current populism of the right and the forces that brought Hitler to power. “The Nazis had a coherent racial theory — grounded in Social Darwinism,” she says. “There was a broad legal and medical framework that came out of that [which is] absent in the populists movements in the U.S. and Europe. [Today there is] a more general resentment — fueled by xenophobia and racism, but less firmly grounded in a theory.”

Still, the European fascists of the 20th century in some ways do resemble elements on the right today, Drummond concedes. It’s worth remembering that fascism found support not just in Germany and Italy but in Franco’s Spain, some parts of Eastern Europe, and even France (Action Francaise, the original version of today’s National Front) and the United Kingdom (Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists.) Fascism had numerous causes, she said, but it surged in all these places largely as a result of the economic turmoil of the 1930s. “After the Depression hit,” she says, “a lot of people lost faith in the political center. You saw people move toward the extremes — to the Communists on the left and the Nazis on the right.”

While much of the U.S. left and right — and many in the middle — are overcome with unyielding truculence these days, their rage is not the same as that seen in Europe, Drummond says. In the United States and Europe, the left is currently fairly small and placid, with the exception of the followers of Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn in Britain and the current regime in Greece. It’s mostly the populist right making noise, she says. And overall, the shouts, for now, are louder here. “Continental Europe has a different political culture,” she says. “They’re alarmed by the loss of decorum in our politics. They look at the American presidential campaign and are amazed by the style of the politicking — not just the substance of policy.”

She also describes salient differences in how anger expresses itself. “You see people making comparisons between black anger and white anger,” says Drummond. “But to me, there’s no comparison. People in Black Lives Matter are angry. But it’s protest toward a goal — a notion of equality.” It was the same with the Black Panther movement, which was launched in the ’60s in Oakland, that preceded them, she says. “The Black Panthers were angry. But they also ran kindergartens, health clinics, places that provided breakfast.”

By contrast, she says, the anger on the populist right in the U.S. and the pro-Brexit U.K. is about scapegoating and unfocused fear. “So much of it is grounded in economic issues,” she says. But when push comes to shove, Brexit was about the “anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant forces.”

So what constitutes the difference between something like the labor movement (driven, in some cases, by the anger of the working-class) or the Civil Rights movement (which saw anger on both sides) and something like fascism or public violence?

Sometimes, it’s the movement’s tone. “Solidarity wasn’t fueled by anger,” Drummond says of the movement for independent trade unionism in Poland in the ’80s and ’90s that was inspired in part by Catholic social teaching. “It was fueled by idealism. Which doesn’t mean that people weren’t angry.”

It also depends on institutions, says Dempsey. “The Populists gave way to the Progressive movement, which owed something to the Populists’ spirit but channeled it in a more institutional direction. And anger was certainly part of the Civil Rights movement, but it was channeled into things like [electing] black mayors.”

Often, the difference between productive and destructive anger comes down to leadership, says Jok, who has lived in or visited Egypt, the former East Germany, and South Africa. Many political movements around the world, he says, begin with the same ingredients. “People say, ‘I work hard, I pay taxes, I abide by the law, I do my part as a citizen. And yet nothing accrues to me, or comes back to my community.’ ” That sense of exploitation can lead in a number of different directions, including the marginalized people turning against each other. It can lead to good policies, or it can be hijacked by an individual aspiring for public office.” What determines the direction anger’s energy will take is something subtle but crucial. “I think it is the morality of the leadership,” Jok says. “When they come to office, they realize they have received a momentous calling. And they need to find their highest selves.”

Scott Timberg, a frequent contributor to LMU Magazine, is the author of “Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class.” He was a Los Angeles Times staff writer for six years, and his work has appeared in The New York Times and elsewhere. Among his feature articles for LMU Magazine are pieces on information chaos as a political tactic and the DACA program. Follow Timberg on Twitter @TheMisreadCity.

This article was posted on Dec. 5, 2016.