Perhaps the biggest prize for the winner of the 2016 presidential election is the ability to shape the Supreme Court and the judicial branch. We spoke with Allan Ides, professor of law and Christopher N. May Chair at Loyola Law School, about the future of the U.S. Supreme Court. Early in his career, Ides clerked with U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Byron R. White. He was interviewed by Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch.

How many Supreme Court openings do you expect the next president will have to fill?

Justice Antonin Scalia’s position remains open, so there is at least one. There also are two justices in their 80s and another who is 78 who are potential retirees. And though I hate to say it, some could die. The new president probably will have the opportunity to appoint three, maybe even four justices in the next four years.

What kind of nominations do you expect to see in the Donald Trump administration?

I am completely baffled by that. He clearly does not respect the Article III judiciary and doesn’t understand judicial independence. Perhaps he will appoint justices in the mold of Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito. But I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Trump is completely unpredictable in terms of the kind of person he’d appoint and what he’d expect of them.

What do you mean by the “Article III judiciary”?

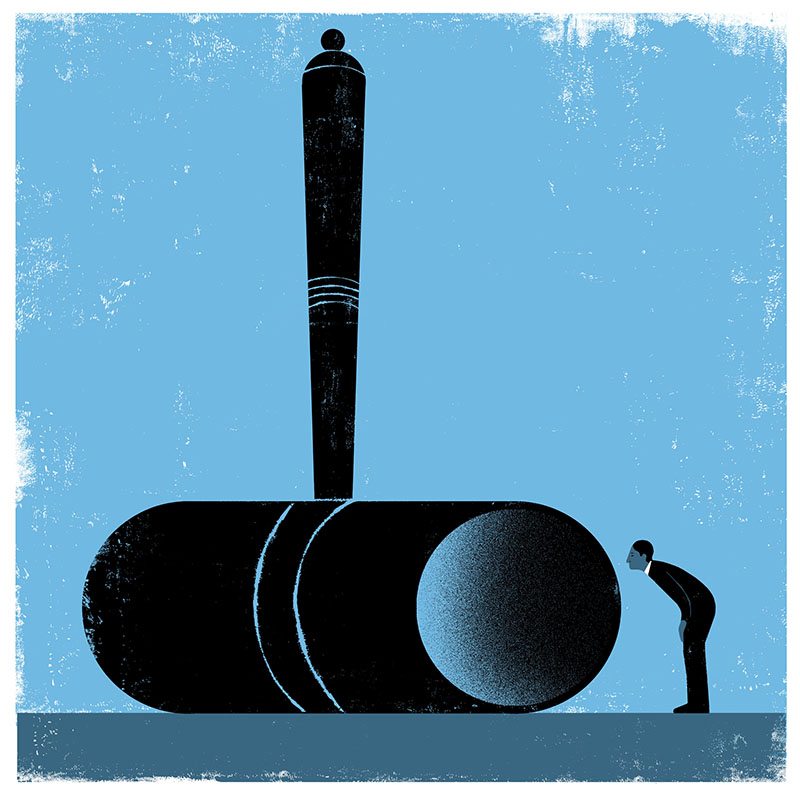

I’m referring to Article III of the Constitution [which deals with] federal judges appointed with life tenure by the president, pursuant to the Constitution, approved by the Senate. They play a special role in our governmental system as a check on the executive and legislative branches, and the states. It’s important that a president appreciate that very delicate function. When a court declares an act of Congress or action by the president unconstitutional, it’s a stunning thing. The judges have to be brave and stand up for what they believe is the correct interpretation of the law or the Constitution. So you need a particularly strong and independent type of person for that job. You need the president and the Senate to understand that.

Are there areas of the law that you expect the court will venture into in the next four years?

There could be more death penalty cases and continuing controversies over the Second Amendment right to bear arms. The 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller case [which dealt with individuals’ right to bear arms especially in regard to self-defense within the home] may be altered. It would not be surprising if more cases on transgender rights started percolating up to the Supreme Court. Immigration and presidential power certainly will be revisited.

What changes can we now expect in the lower courts?

There are many vacancies on the lower federal courts as the Republican Party has stalled on its consideration of President Obama’s nominees. So President Trump will have a huge opportunity to change the face of the lower federal courts. Based on some of his campaign statements about federal judges, he doesn’t seem to appreciate the independent role of the judiciary. My hunch is that he will create some type of advisory committee to help him identify potential appointees. That may serve as an antidote from some of his more extreme views.

Has the court changed in the past 50 years in how it views its own responsibilities?

Yes. The court views itself much less as an institution that decides a case according to the law and more as responsible for making policy judgments — within the confines of a judicial function but, still, policy judgments. When I teach constitutional law, I tell students an interpretation of the Constitution is not necessarily what the Constitution is but what the justice thinks it ought to be. As cynical as that sounds, I think it’s true for liberals and conservatives.