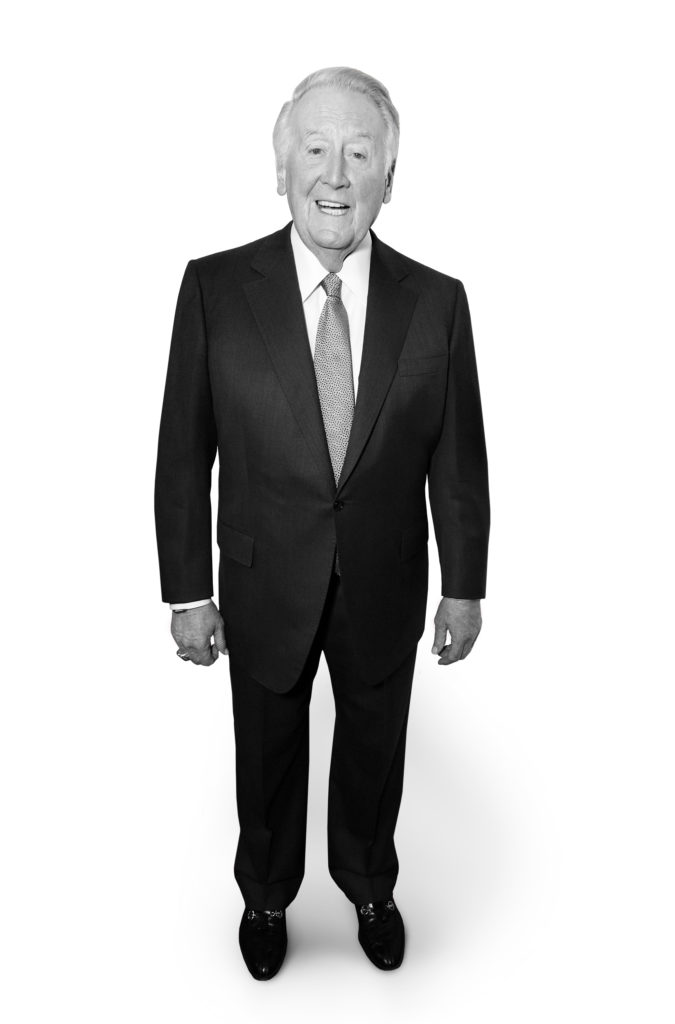

Vin Scully P’95, P’99 and grandparent to three additional alumni came to Los Angeles when the Dodgers moved here from Brooklyn in 1958. In the decades that followed, he became the voice of the franchise and, for many, an iconic symbol of L.A. itself. But Scully was born and raised a New Yorker. A graduate of Fordham Prep High School and Fordham University, he is the product of a Jesuit education. Scully served as emcee at the 109th Commencement Exercises at SoFi Stadium on July 31, 2021 — the feast day of St. Ignatius, founder of the Society of Jesus. Scully was interviewed by Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch. A shorter version of this conversation appeared in the summer 2021 edition (Vol. 10, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.

What do you miss about not being in the press box on game day?

I miss people: the person who runs the elevator, the custodian of the press box. I’d usually greet the visiting radio and TV people of whichever team was playing that night. I tried to meet the challenge of doing the play-by-play and make it a little more interesting, informative if possible and even slightly entertaining if I could find something to put a smile on someone’s face. But the actual games — I don’t miss them nearly as much as the people.

How would you describe the lasting impact on your life of your Jesuit education?

In one word: faith. That’s what I’ve been holding onto with both hands as long as I’ve lived. I spent eight years at what they call Rose Hill, which is the Fordham University and Fordham Prep campus. So, I was deeply immersed in Jesuit life.

When I was in high school at Fordham Prep, I was going to represent the prep at an elocution contest. The president summoned me to his office and asked, “What are you going to wear when you represent us?” I said, “White shirt, striped tie. I have only one suit.” And then I said, “And oxblood shoes.” He looked me and said, “Oxblood?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Do you have a pair of black shoes?” I said, “No.” He said, “Alright, come to my office tomorrow.” The next day, I walked in to his office and, honestly, there were at least 20 pair of black shoes on the carpet. He had gone to every priest and seminarian and borrowed a pair of black shoes. I tried them all on, like Cinderella, and one pair fit. So, those were the shoes that I wore to the elocution contest. By the way, I didn’t win. I think I finished third. That was par for the course in terms of the interest that they showed for their students. It was a marvelous time.

What was your major at Fordham?

I really majored in radio. I had gone into the Navy for one year. I did not make a ripple on the water. I didn’t go anywhere or do anything. But the shock of my life was when I came back to school: I found out that there was an FM station. Not a college station, but a legitimate, paying FM station with quite an audience in and around New York. Of course, that was what I was looking for. Oh, sure, I guess I was an English major, but it was the radio station that was so precious to me.

We know the names of baseball’s stars and will remember them as long as we live. But how should we value the utility infielders, long-relief pitchers and the guys hired just to pinch hit?

If you look at a ballclub, of the 26 players you have at least 13 pitchers. The bulk of them are sitting quietly in the bullpen. They’re like so many of us in this world who toil, who are not going to make a headline. We’re not going to do anything but work hard, get paid and raise a family. When you look at a game, yes, there are stars, just as in life itself, but the bulk of the machinery, as in life, is the unsung who work and produce. I think that’s the big lesson to be learned.

What career might you have pursued if your broadcasting career had failed?

I never thought of failure. I just plodded on and was fortunate. I might have been a bit of a writer who went on to write for a newspaper or something. I dreamt of being a broadcaster when I was 8 years old. I remember a nun in the eighth grade, Sr. Virginia Maria, God bless her. When she learned I wanted to be a sports announcer, which was unheard of in the ’30s, she had me stand up every day and read for just a few minutes. After a while, I became accustomed to addressing my classmates and doing whatever she wanted me to do on my feet. I think that helped a great deal.

These were Sisters of Charity, and there was a period when they were far from charitable to a little red-head. The reason, which sounds pre-historic, is that I am naturally left-handed. I do everything left-handed. When I was in grammar school, that was not allowed, as shocking as that seems. Every day, I’d go to school, and I’d pick something up and a good sister would come by and whack my left hand with a ruler, trying to get me be right-handed. One night I came home, and my mother saw my beaten-up left hand — because occasionally the nuns would hit me not with the flat side of the ruler but with the edge with the metal, which broke the skin. So, my mother immediately figured I had done something wrong and was punished. She had good grounds to think that way, because probably 95% of the time she’d have been right. But in this case, I told her, “They’re beating my left hand because they don’t want me to use it.” Fortunately, we had a wonderful Jewish doctor, and he wrote a letter to the nun, saying that what they were doing — forcing me to be right-handed — could perhaps cause me to stutter. And he wrote, “Besides, dear sisters, why would you wish to change God’s work?” Well, grand slam, home run. I was allowed to be left-handed, and, I guess as they say, the rest is history.

What’s your advice to the student who is broadcasting LMU’s baseball games from the Page Stadium press box and wonders if there’s a career in the future?

I would say it’s about mental outlook. Don’t be discouraged; it’s a big world. There are radio stations and television stations all over, twice as many as when I was starting out. I’d work hard, and I’d give it a good five years. If I’m not where I want to be after five years, then, OK, I’d go somewhere else.

What have you been proudest of in your work with the Dodgers?

When I look back over my life, at all the great breaks and things that happened, it was as if at an early age I was handed a book of instructions. I followed the instructions, and things worked out well. But proud? No, not even a little. In fact, if I thought I was proud, I’d kick my fanny right down the street. I do thank God. I do that very, very much.