The United States meets Central America at L.A.’s Westlake intersection. Rubén Martínez finds that survival is one of the many stories found at this hemispheric meeting place.

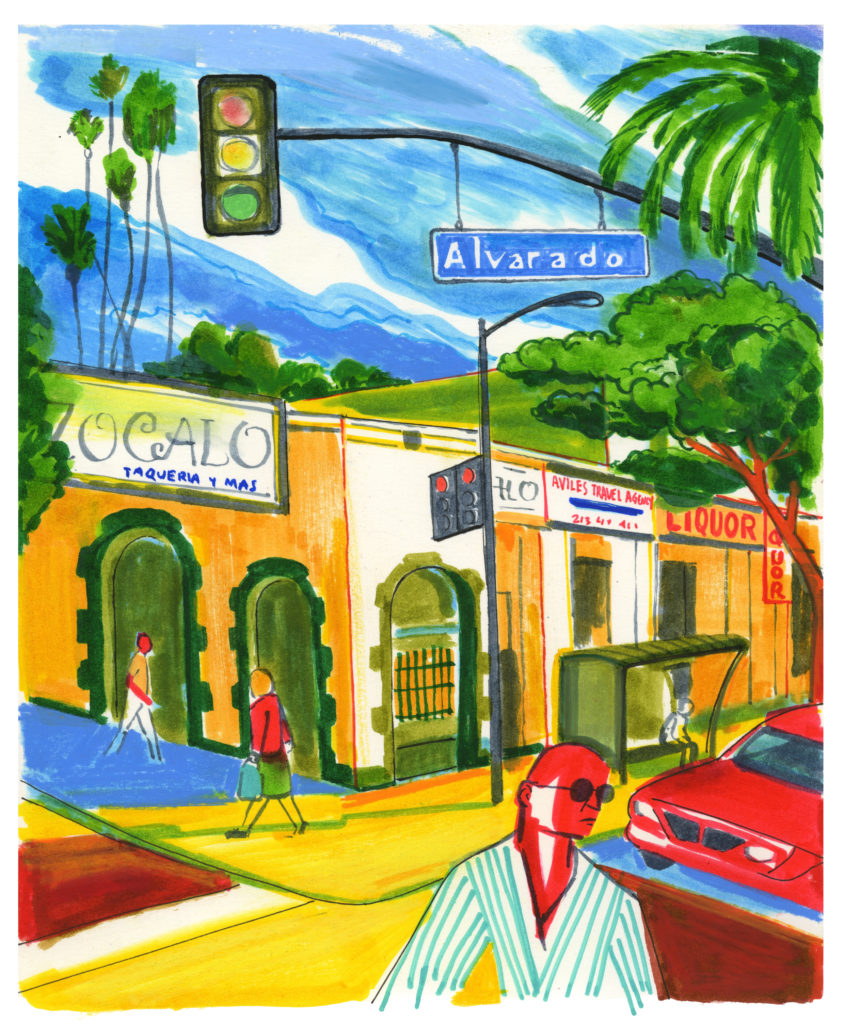

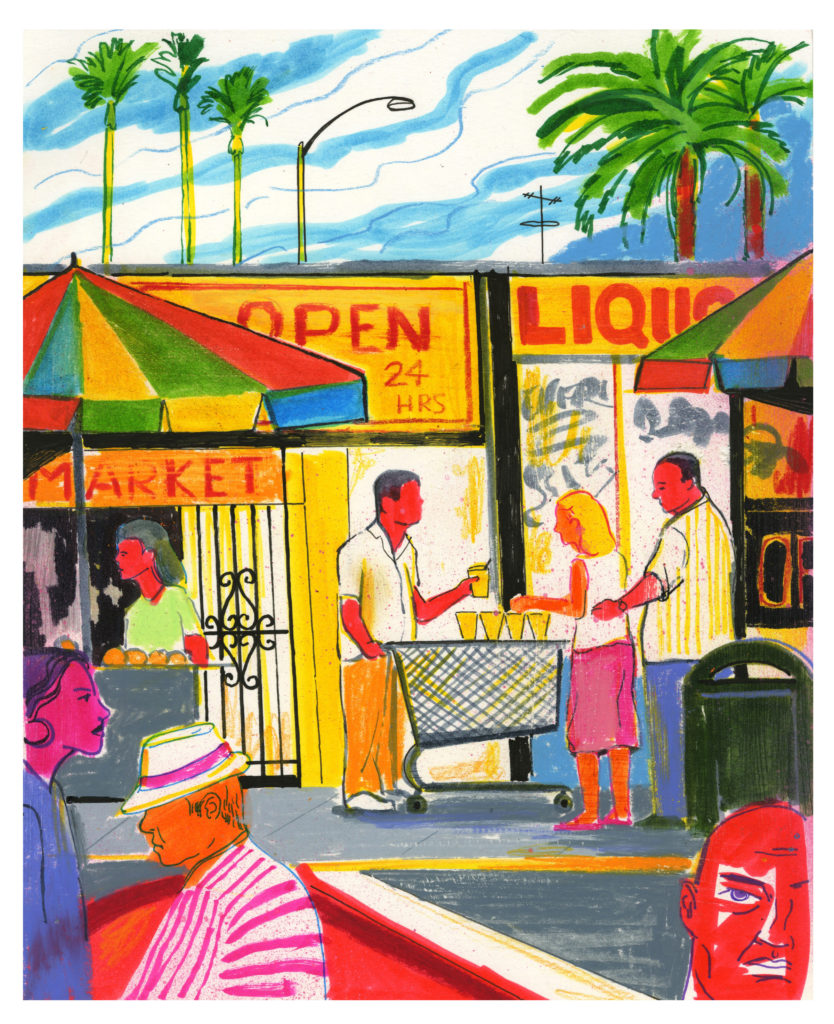

Alvarado and 3rd. Sooty palms soar above sidewalk vendors under rainbow umbrellas slicing chilled fresh fruit amid the whoosh of eight lanes of traffic …

So began a sketch I wrote in early February of 2020 about the intersection at the heart of Westlake, a district bordered by Historic Filipinotown to the north, Downtown to the east, Koreatown to the west and its sister-in-demographics Pico-Union to the south.

I went on to write that the neighborhood, one of L.A.’s densest, has also long been known as “Little Central America” — a gateway for refugees, dreamers, and schemers; for poets and mara members; for, as the great 20th-century Salvadoran bard Roque Dalton wrote, a people famous for being “los hacelotodo, los vendelotodo, los comelotodo”(the do-it-alls, the sell-it-alls, the eat-it-alls).

It was going to be a story about memory, personal and collective, about people who’ve endured civil wars, earthquakes, hurricanes, slumlords, the LAPD Rampart Division scandal of the late ’90s, and the ghosts they live with and among. It is a place for survivors, as well as a place that is not always easy to survive.

Then came March 20, 2020, the day Mayor Eric Garcetti issued his “safer at home” order, and at Alvarado and 3rd the traffic hushed, the bustling street vending strip a couple of blocks south of the intersection abruptly disappeared, and the neighborhood, along with the rest of the world, waited for the plague to hit.

From the beginning, it was obvious that Westlake was among the neighborhoods most vulnerable to COVID-19. Since the 1990s, it has claimed fame for having a population density rivalling the most crowded parts of Manhattan. A crush of 38,214 residents per square mile live here, second only to Koreatown. Thousands of residents either lost their jobs (heavily overrepresented in the service sector or the informal economy, i.e. street vending), or continued to perform labor deemed essential, exposing them to infection.

The epidemiological picture is as simple as it as tragic: Population density plus an inability to completely shelter at home (like I and my professor colleagues across the country did) equals higher risk for infection and death. As of late September 2021, Westlake had a death rate of 537 per 100,000 residents, placing it among the top five hardest-hit communities in the city. By comparison, Westchester had 57 deaths per 100,000.

The Latinx trait of tight-knit families living in multi-generational households — a matter of both culture and socioeconomics, that is, of survival — is precisely what made Covid so virulent and deadly in Westlake.

The ghosts and the living intermingle; painful and healing journeys converge at the intersection of Alvarado and 3rd.

I RETURN TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD 19 months after my initial visit. Los hacelotodo, los vendelotodo, los comeletodo are still here. And Westlake is ever-more inhabited by ghosts — but not all of them are a burden.

My pre-pandemic writing assignment was to write about any street intersection in the city. Alvarado and 3rdwas the first and only one I really considered. I swore I wasn’t going to write a typical gentrification story, another totalizing lament to the departed soul of a neighborhood of color overwhelmed by new (mostly white) money.

There are signs of gentrification in Westlake and Pico-Union, a tide steadily inching westward from a Downtown that’s been thoroughly transformed in the past generation, with the likes of live-work spaces and professional dog walkers. I saw a banner on a building on Wilshire east of Alvarado offering “office and creative space,” an obvious pitch to a professional class that so far has been wary of colonizing the Central American barrio. Which doesn’t keep gentrification-promoting websites like Areavibes or Niche from making the pitch. The former gives Westlake an A+ in “amenities” (I wonder if they mean the fact that there are two franchises of Pollo Campero, Guatemala’s fast food gift to the world, within a mile of each other?). The latter makes the neighborhood look whiter by neglecting to post ethnicity alongside race, thus erasing most of the Latinx population (which can be of any race, a contradiction that demographers, the U.S. Census, the political class and we Latinx have yet to resolve.)

But I swore this wouldn’t be a story of gentrification, so let’s stay with who’s still here in the present, with the neighborhood’s memory — and my family’s memories within it.

Let’s stand at Alvarado and 3rd, and then cast our gaze outward through time and space. The intersection is anchored by the building that housed St. Vincent’s hospital, its parking lot completely empty today. This is where my connection to the neighborhood begins: I was born at St. Vincent’s. When I was a small child that’s where I visited my grandfather in intensive care after a heart attack. When I was a young adult, I came back for my grandmother’s final breaths.

Six years ago, my mother was there for an extended stay after a diagnosis of stage 4 multiple myeloma. My father almost died of sepsis on the sixth floor shortly after my mother passed.

The city’s first hospital, founded in 1858 by Vincentian nuns, closed in January 2020 after its corporate parent declared bankruptcy. Billionaire transplant surgeon and entrepreneur Patrick Soon-Shiong, owner of the Los Angeles Times, quickly bought the building and converted it into a dedicated pandemic hospital during the first surge. Many Westlake residents gravely ill with the virus wound up here, and many of them died. The corporeal and narrative traces they left behind, along with the hospital’s 163-year history, the 1,100 employees laid off just before the pandemic (along with the legions of employees past) and my family’s own ghosts add up to a vast, haunted presence-absence.

But it is not only a place of painful memory for me nor for the untold numbers of others who worked, died, cared, cured, survived here. For me, there were lucid and even playful conversations that approaching death brings. And the countless interactions with staff, the thanking and cursing and small-talking with nurses and doctors and techs. I memorized the names of security guards, phlebotomists and cafeteria cashiers. Even amid the ruins of American healthcare, there was still relationship, empathy and grace at the corner of Alvarado and 3rd.

The emptiness of the old hospital is somehow echoed, kitty corner, at the long-shuttered Zócalo restaurant, with its tagged, grimy, gated façade.

This Friday morning in early September, the traffic flows and ebbs to the rhythm of the stop lights, most of it is passing through: commuters on their way into and out of Downtown. The Starbucks on the northeast corner offers drive-thru service only. Much of the foot traffic is comprised of people getting on or off the bus lines, many transferring to the Metro Red Line at the Westlake/MacArthur Park station.

I head south on Alvarado as the owners of ma-and-pa storefronts undertake their morning rituals, hanging merchandise on the opened security gates, rinsing the sidewalk with sudsy water (just as they would do in the old country). The street vendors are setting up too, just a few per block next to Ross Dress for Less between Maryland and 6th Streets, and then choking the sidewalk approaching Wilshire. Under the sooty palms and rainbow umbrellas.

At the first stand I stop at, Danilo Cruz puts the finishing touches on a straightforward display of water, sliced fruit and fresh-squeezed orange juice. Like so many of the immigrants I’ve interviewed over the years, he is hungry to be heard. Hearing his accent, I mistake him for a Salvadoran; Honduran, he corrects me. In his late 40s or early 50s, he’s dyed his hair jet black, slicked it with product on top and, after the fashion, buzzed it on the sides. He has copper skin, small, flashing black eyes, and speaks in a quick urban cadence.

“Gracias a Dios,” he says, his business is OK. After lockdown, he didn’t come out to sell for about four months, but thankfully his part-time janitorial job in Pasadena didn’t lay him off and he made do on that salary alone.

“I’m still here because I’ve learned from my mistakes,” he says. He came north as a young man and got caught up in the business of the street — of those young men there have been and remain plenty in Westlake. “Drugs have done a lot of damage here, mang,” he says, using the colloquial Spanish version of “man.”

“En este país, soy escoria,” he says; in this country, he’s considered scum, in spite of the fact that he’s learned from his mistakes, and all those years of hard, honest work. (In Spanish, “trabajo duro y honesto” transcends cliché by how meaningful and durable a description it is when Latin Americans describe their labor.)

A young couple buy fresh orange juices. Danilo rearranges the remaining plastic cups on his stand, fashioned from a piece of plywood over a grocery shopping cart.

Six years selling on Alvarado, never taken a dime from the government. He not only learned from his mistakes, he says, he has paid for them.

The pandemic? He shrugs his shoulders.

“We’re still here, aren’t we?” he says, suddenly switching to the first person plural.

Westlake was a neighborhood you could certainly get in trouble in, but also one vibrating with difference, the good kind.

MY MEMORY INTERSECTS with the neighborhood’s. My late mother was an immigrant from El Salvador. She never lived in the area, but an aunt of hers did, my tía Mila (the diminutive for Milagros), a vivacious woman with a big voice and lots of stories to tell. She was among the pioneers of the Central American presence in Pico-Union. Mila and her husband purchased a three-bedroom house on Valencia between Pico and Venice (to which they added an unpermitted mother-in-law unit in the back, as untold numbers of Angelenos have done for generations). Her son, my cousin Mario Castaneda, has been a life-long educator, attaining an Ed.D. and recently retiring from a teaching career at Cal State L.A.

Mario remembers a cluster of Central American families in the area. The kids he grew up with wound their way through public and parochial schools, college and law school, heroin addiction, the stock market, Vietnam, the Riverside Sheriff’s Department, UCLA, out-marriage, divorce, their own kids and grandkids.

The neighborhood was decidedly more mixed when Mario grew up here in the ’60s and ’70s. You heard Puerto Rican and Ecuadorian and Mexican accents in Spanish. There were Greek immigrants, Eastern European Jews (Langer’s Deli on Alvarado and 7th, established in 1947, tells that story), Albanians, every nationality of Asian. Mario went to senior prom at Belmont High with a Filipina.

Westlake was a neighborhood where you could certainly get in trouble in, but also one pulsing with difference, the good kind, the kind that L.A. seems to be losing as immigration and gentrification transform the geography. The city is becoming a demographic contradiction: more diverse and more segregated at the same time.

If a wave of gentrification washes over Westlake, it will erase sameness with sameness — replacing one monad with another.

Then again, certain kinds of sameness can mean solidarity. And solidarity can mean survival.

Westlake and the adjacent Pico-Union district received tens of thousands of refugees from the Salvadoran and Guatemalan civil wars of the 1980s (there were over half a million Central Americans in the Los Angeles metropolitan area as of 2019). The demographic upheaval rapidly remade the neighborhood.

During the wars, several churches in Los Angeles, including the First Unitarian Church at 8th and Vermont, became sites of sanctuary, offering material support and shelter to survivors of U.S.-sponsored terror in their homelands, as well as carrying out public ministry against American intervention.

I played a modest role in that story, as a journalist and what today would be called an “artivist” (artist-activist), helping to stage interdisciplinary performances (music, poetry, sketch theater, political speeches), taking my place in the lineage of American progressivism and Latin American revolution. At First Unitarian, I met octogenarian veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, volunteers who fought on the republican side against the fascists in the Spanish civil war of the 1930s. And I met revolutionaries from El Salvador, carrying the ghosts of loved ones violated and disappeared by U.S.-backed death squads. It was wartime (even as Ronald Reagan proclaimed “morning in America”) and Westlake was like an emotional field hospital. We tried to heal the wounds by embracing life. We fought the good fight with cumbias and pupusas, declaiming verses and stenciling protest signs.

Even as many refugees found solidarity, healing and new love in Westlake, others, especially children, encountered an echo of the terror they’d left behind. The neighborhood had long been home to what once was the exclusively Mexican American 18th Street gang. Central American youth formed their own gang, MS-13, essentially to defend themselves — and compete in the shadow side of capitalism, the drug economy. The LAPD, as was often the case across the 20th century, made matters worse, with Rampart Station cops running their own corrupt cliques alongside the gangs.

The cumulative effect of these violences exploded during the Rodney King Uprising of 1992. To the surprise of many, Westlake and Pico-Union saw heavy looting and arson; some of it opportunistic, much of it borne of desperation, fear, and rage against consistently confrontational and corrupt policing. The LAPD responded with mass arrests and by turning suspected undocumented immigrants over to what was then called the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Immigration and Customs Enforcement today) for deportation, in violation of longstanding city policy that banned such cooperation between the agencies. Some deportees were members of the MS-13 and 18th Street (which had taken on Central American members as well). That is the origin point of the devastating wave of organized crime in Central America today. MS-13: made in America.

In this way, the corner of Alvarado and 3rd arrived at the center of a global cyclone, where it remains today. A geography of violence, and one of hope as well, hard won as it is. A few blocks away, at 7th and Hoover, is the Central American Resource Center (once the Central American Refugee Center), established at the height of the crisis in the 1980s and on the front lines again today, where recent arrivals find orientation and legal aid, in some cases counseled by those who survived the traumatic journeys of a generation ago.

Alvarado and 3rd has risen and fallen, like its roly-poly hills that were cultivated by the Tongva, became ranch lands with the Californios, were crowned with oil derricks by Edward Doheny, and later saw Victorian mansions, brick hotels and tenements. More ghosts: One of the city’s deadliest fires — a case of gang-related arson — took 10 lives at the Burlington Apartments in 1993, just a few blocks away from our intersection.

The ghosts and the living intermingle; painful and healing journeys converge at the intersection of Alvarado and 3rd.

Dina Avilés fled the Salvadoran civil war in 1981 and found another kind of war on the streets of Westlake.

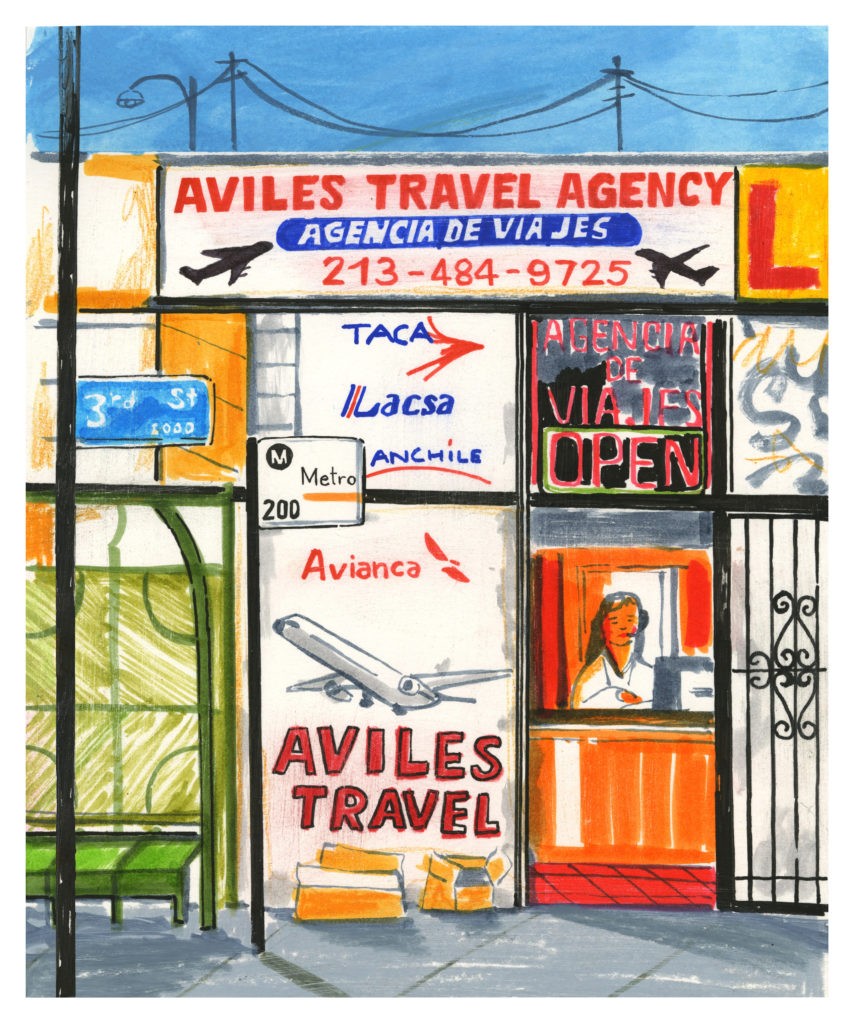

FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS, Dina Avilés, owner of the Avilés Travel Agency, has looked out from her perch next to the ghost of the Zócalo restaurant on the southeast corner of Alvarado and 3rd. She fled the Salvadoran civil war in 1981 and found another kind of war here, on the streets of Westlake. She long ago realized that she’ll never go back — how can she if the caravans of refugees still head north? Besides, Avilés Travel threads the old country and the new one together, bringing San Salvador to Westlake and Westlake to San Salvador, reconciling past and present, introducing the future one flight at a time.

When I first met her in February of 2020, she told me that her old-school business was still going strong.

In a buoyant middle age and leopard-print blouse, glasses pushed back on her head, a headset attached to the landline on her desk, she talks of the daily parade past her door — vendors, school children, the unhoused. Many of them fled the same terror she did.

“People of a certain age,” she told me then, “still want a voice on the phone, someone to look up the cheapest fare for them.”

When I poked my head in the door 19 months later, she was again wearing a leopard-print blouse.

The pandemic hit her hard. The storefront was closed for seven months. The only business she did was changing tickets that had been booked before lockdown. She had to lay off all her employees. She received some CARES Act money, but things were still so tight that she had to sell a car and jewelry to get by. Her landlord helped out by forgiving rent.

Today, she says, business has returned to about 60 percent of its pre-pandemic level. Her number one destination remains El Salvador.

“Rain, lightning, or thunder, there are three flights a day,” she says “Delta, United, American.” Always full.

She’d already experienced one severe downturn — 9/11. Her Salvadoran customers were there for her then, too. “The airlines and other travel agencies were really impressed by our people.”

To her left, glass shelves display old plastic models of 707s and 727s. I remember them from the Pan American flights I boarded as a small child with my mother to visit relatives. Directly behind her on the wall hangs a painting of Salvadoran women balancing baskets on their heads filled with goods to sell at market, an image that always impressed me — a symbol of grace amid trabajo duro y honesto.

The pain and fear from the pandemic will linger, Dina says. But Westlake will abide. “We’ve seen it all, the ups and downs and in-betweens. We know how to survive.”

Rubén Martínez is a professor of English and Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies at LMU. He holds the Fletcher Jones Chair in Literature and Writing in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. His “Journey South” appeared in the winter 2015 issue (Vol. 6, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.