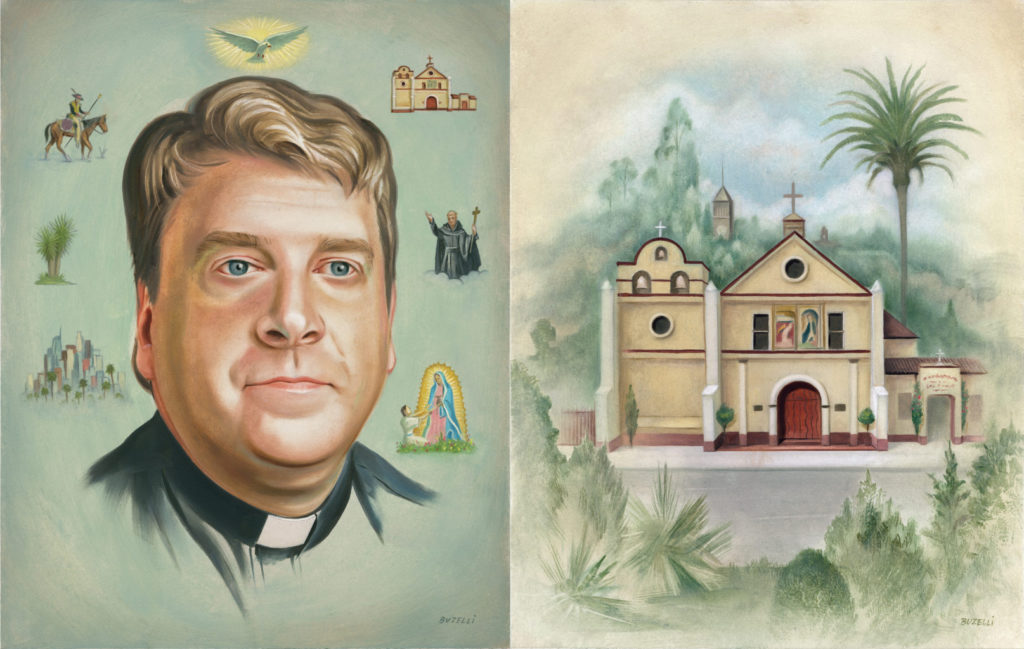

Sean Dempsey, S.J., is an assistant professor of history in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts whose research focuses on the intersections of religion, social thought and urban politics in the 20th century. His Ph.D. dissertation was on “The Politics of Dignity: Social Christianity and the Making of Global Los Angeles.” The Archdiocese of Los Angeles is the largest diocese in the United States. We spoke with Dempsey about the history of the Catholic Church and religious movements and groups in Los Angeles and about the interplay between religious organizations and current issues. He was interviewed by Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch.

How do you describe the role of Catholicism in L.A.’s culture?

The historical question of Catholicism’s role in L.A. is an interesting one. Since Los Angeles is originally a Spanish and, later, a Mexican city, Catholicism played at least some role in that history. But as Los Angeles grew into an American city, it arguably grew less Catholic. It became a place of settlement largely for Protestant Midwesterners who built modern Los Angeles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with that Mexican and Mexican American Catholic population still present but marginalized for a variety of reasons. In recent years, with the city becoming much more of a Latino city again, you could argue that Catholicism either has become or is in the process of becoming more important in shaping the city. The historical period I look at is right after World War II, a transitional period when that old Protestant elite is giving way to Catholics and Jews, especially, but also all the other religious groups that L.A. is known for. So, after a period of transition, you could now say L.A. is back where it started as largely a Mexican American and largely Catholic city.

• Listen: Sean Dempsey S.J. on the Catholic vote in 2020 on the LMU Magazine Off Press podcast.

Where do you see the signs of Catholic influence in the early Spanish and Mexican period of Los Angeles, on one hand, and in today’s L.A. as well?

We certainly see the influence of Catholicism, especially a Latino or Hispanic Catholicism, in the very origins of the city, although L.A. was founded, really, as an agricultural market town. We see it in the original church, La Placita, whose official name is Iglesia Nuestra Señora Reina De Los Angeles (Our Lady Queen of Los Angeles), which throughout Los Angeles’ history has been a center of Catholicism, and of Mexican and Mexican American identity. A topic I study and write about quite a bit is the immigration rights activism that has historically come out of that parish. I’m especially interested in the activism of Father Luis Olivares, a Claretian priest very active in the ’70s and ’80s in L.A. who blended a specifically Latino brand of Catholicism with social justice activism. I see that legacy continuing to play out even now in the secular progressive politics in the city. It may be less overtly, institutionally Catholic, but certainly the framing of issues, especially around immigration and immigrant rights, is still very prevalent in the politics of the city and the political culture of the city.

Does that influence affect the arts culture of the city?

Very much so. Recently I went to the L.A. exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, where you can see a Latino, Catholic-infused popular art that has roots, for example, in the work of muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. There’s an almost baroque-style in the art that I find very indicative of Los Angeles — this kaleidoscopic city, where you almost cannot cram in enough imagery to fully represent the town. I love the “over-the-top-ness” about it, but I mean that in the best possible way: Los Angeles can’t be contained, or it can’t be imagined in simply one way but must be imagined in a multiplicity of ways at all times.

Is it possible to underestimate the impact of religious institutions in Los Angeles today?

I think so. Not long ago, I was on a panel at the Huntington Library in Pasadena. We were discussing the controversy over sanctuary cities and whether L.A. should designate itself as one — which L.A. seems to be conflicted about politically. As the historian on the panel, I pointed out that L.A. was a sanctuary city in the 1980s, and that it was largely the result of efforts by religious activists that made it one briefly until there was a big fight on the city council. My fellow panelists, who were present-day activists in the sanctuary movement, had no idea of the religious roots of sanctuary designation and this movement. One of the things I write about is uncovering the religious roots of a lot of things going on today in cities like Los Angeles. We hear from politicians, such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, about the fight for economic dignity, for immigrants’ rights, for sanctuary cities — a moral vision for urban living and politics and, by extension, a global model for living. I think there are very distinct religious roots for that vision, especially in a city like Los Angeles. And because of some of that institutional decline we can easily forget where those ideas and movements came from. A lot of what we’re talking about today was inspired by a movement of religious activism of prior generations.

Whatever the future holds is not going to be something that is exclusively catholic. But i think the church can lend its voice, energies and spirit to a lot of the good things that are happening.

Is immigration in the modern era bringing a renewed Protestant Christianity to Los Angeles even though these immigrant populations are coming from historically Catholic regions?

Yes, absolutely. One of the big global stories of recent religious history is the explosion of evangelical and/or Pentecostal churches in Latin America, oftentimes responding to gaps or the ways in which the Catholic church was, frankly, failing to serve especially when it came to the poor or people at the margins of Latin American society. Latin American evangelicalism and Pentecostalism is very different from its American roots, although these are originally U.S. movements. But oftentimes these traditions bring a kind of social justice and social activism sensibility that’s far more progressive than that of their spiritual cousins in the American South. So, it’s a very interesting phenomenon in which American religion has pollinated Latin America and in turn Latin American evangelicalism has been coming back into the U.S. through immigration. That’s a story that’s only beginning to be understood.

As the Catholic Church grew in eastern U.S. cities, it exerted social and political power from the top down on those cities. Does the growing Catholic Church in Los Angeles have that kind of influence today?

I certainly think we are in a moment in which there has been a noted decline of the top-down public voice of churches and religious institutions. It wasn’t long ago that faith leaders were big players on the political scene, and you’d regularly read their comments in the L.A. Times and hear them on the local news. They had a quasi-civic and political role. That’s true today of certain Catholic archbishops, including our own, Archbishop José H. Gomez. But it’s not true to the degree that it once was. Where there is still vibrancy is from the bottom up, where churches — whether storefront churches or urban Catholic parishes — are still centers of what I call “dignitarian politics” or politics of dignity, involving things like immigrants’ rights, the rights to housing and health care. It’s a broadly inclusive politics that we see bubbling up in Los Angeles and, frankly, in other U.S. cities these days. I feel that churches, synagogues and other places of worship, and organizations affiliated with faith communities, are at the bottom of a lot of this.

Is the future of the church’s ability to shape society in restoring its institutional power? Or is it in supporting individuals who are shaped by church and the religious and quasi-religious organizations you’re describing?

I think the latter. When I look into the crystal ball, it seems to me that if there is a future of American Catholicism going forward, whether in Los Angeles or elsewhere, it is an immigrant Catholicism again, it’s a Latino and Asian Catholicism primarily. In those cultures, Catholicism has always been as much about culture, custom, family and tradition as it has been about the institutional church and the clergy. Those models we associate more with Irish American and German American Catholicism, which centers on the parish, the pastor and the priest. So, Los Angeles is potentially a great model of where the church goes from here in this time of crisis for the institutional church. But can it continue to endure, inspire and influence the grassroots culture of cities and elsewhere from this bottom-up model? Can it continue to exist in homes, block parties or organizations like Homeboy Industries, which are not specifically “Church” with a capital C but that definitely embody the spirit of a certain kind of Catholicism that’s very rich.

Are you saying that if the Catholic Church is to survive the present sexual abuse crisis, it must continue to associate itself with a bottom-up model of shaping society?

The crisis in the church is, in a way, a global reckoning of old structures — some of them simply antiquated, some of them frankly unjust or oppressive — that are giving way to new realities. This is not to say there is no role for the institutional church. As a priest, I am part of it so I hope there is a continued role. But can it be recalibrated to new realities? Can it truly serve the people, as it was always intended to? Can it exist alongside or underneath, as opposed to above so to speak? In my more hopeful moments, I hope that will happen: a church that can accompany both the specifically Catholic things happening but also those in secular society and other faith traditions that speak to the common good and help build community and a sense of justice. Whatever the future holds is not going to be something that is exclusively Catholic. But I think the church can lend its voice, energies and spirit to a lot of the good things that are happening. That’s nothing completely new; that’s very much the spirit of the Second Vatican Council that has been imperfectly expressed in the past 50 years. But maybe it’s time, as Pope Francis is saying, to implement that spirit.

I can imagine voices in Catholic institutions in eastern U.S. cities saying, “That may be your reality in Los Angeles, but it’s not ours here in New York City.” Or Philadelphia, or Chicago.

We’re fortunate in some ways in that we have a very different expression of Catholicism in Los Angeles and a very different Catholic history. On the East Coast, we have a church built by immigrant groups but, as I said, focused on the institutions of the church, the schools, the clergy. It seems to me that that’s the church that’s either growing radically smaller or coming in for drastic change. There’s a sadness and mournfulness to that on the East Coast, which largely speaks to the wild success for so long of that model. Urban Catholicism in the Northeast and the upper Midwest was an incredible constellation of institutions. As one historian has said, it’s arguably the greatest achievement of the American working class — the building of Catholic schools, hospitals and charities, mostly done with the donations of ordinary working people over decades. That model built a culture and a political culture in many of those cities. It built economic power and opportunities for people, and not just Catholics. However, I don’t think there’s any going back — there or here. Maybe Los Angeles provides a model forward toward a hopeful future not only for itself but also for places like Chicago or Detroit.

This article appeared in the spring 2019 issue (Vol. 9, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.