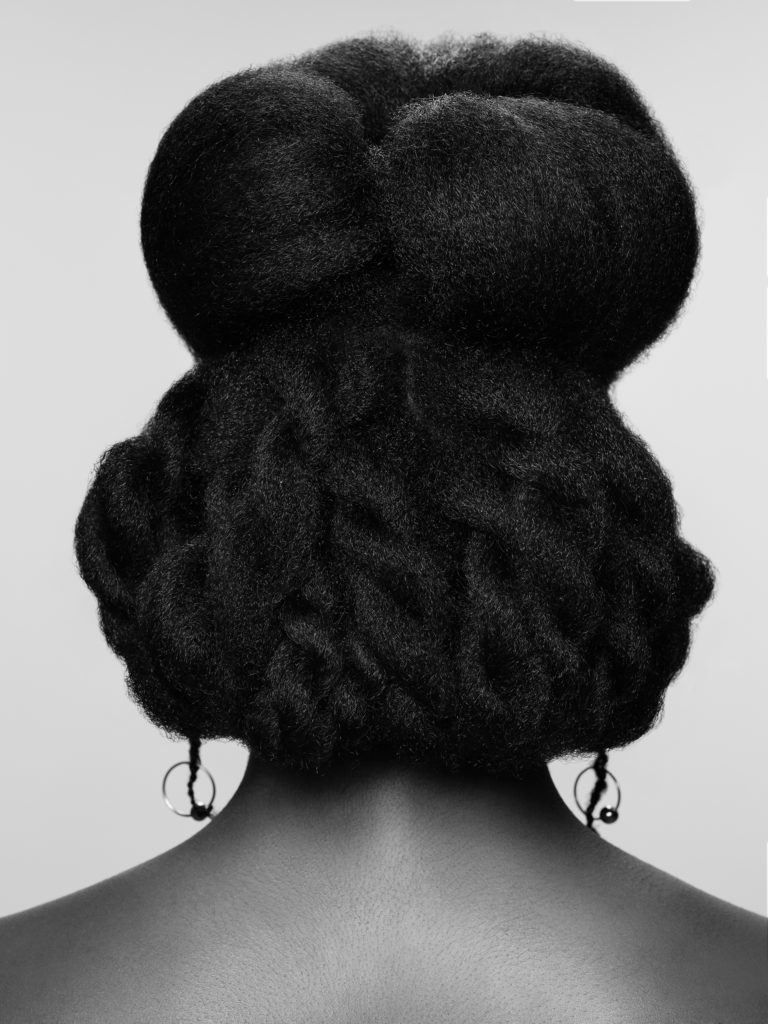

I am not my hair

I am not this skin

I am the soul that lives within

—India Arie, “I Am Not My Hair”

Rumi wrote about it. India Arie sang about it. But scores of Black women choosing to wear their natural hair in professional spaces are too often penalized for it.

“On the topic of natural hair — and accepting our natural hair as Black women — people are always going to have an opinion about what’s growing out of your personal scalp,” says Stephanie Bell ’20 while talking about the making her capstone documentary film, “Defending Our Crowns.” The 13-minute final undergraduate project at LMU examines the pressures Black women face in fashion and entertainment to conform to European hair standards.

Respectability politics is for real, and oftentimes our worth as Black people is tied to how we wear our hair. In fact, according to Bell, the issue of “good hair” and colorism has become so problematic that generations of Black women have internalized this discrimination as a normal fact of life.

She’s right. And in 2019, California became the first state in the U.S. to pass the CROWN Act — Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural hair — which ends race-based hair discrimination in workplaces and in K–12 public and charter schools. Championed by then-California Senator Holly Mitchell and galvanized by Esi Eggleston Bracey, former COO and head of beauty and personal care for Unilever PLC North America, the CROWN Act has become a movement in government and private sectors aimed at ending hair discrimination nationwide.

“This isn’t about hair,” says Mitchell, now a Los Angeles County Supervisor. “This is about discrimination, and us creating a culture shift where we acknowledge that a Eurocentric standard of beauty, i.e., straight hair, is not true to us.”

“It certainly doesn’t define professionalism,” adds Mitchell, who wore locs for 17 years, “and it certainly shouldn’t justify little girls being suspended from school because their mothers sent them to school with box braids.”

The issue of “good hair” and colorism has become so problematic that generations of Black women have internalized this discrimination as a normal fact of life.

Michelle Amor Gillie, clinical professor of screenwriting in the LMU School of Film and Television, says Black women have become used to a kind of code switching — which when speaking is alternating between two or more dialects, styles or registers for social and professional engagement — with their hair. She sees it as much on campus as in Hollywood.

“I haven’t had flack about my ’fro,” she says about wearing her hair natural as a professor, “but I definitely notice when I straighten my hair, people are extra, ‘Oh my god, it’s so pretty, oh my god, oh my god!’ And they love to tell me I look younger. But when I rock my ’fro, they don’t really say much.”

“To be honest with you,” she adds, “I will straighten my hair for an interview. Then when I get the job, I’ll wash it out, and then it’s back to the ’fro. I’ve definitely done that. And it is frustrating.”

While Amor Gillie says she doesn’t wear her hair to please others — she likes it straight or curly — she is aware that different styles have different impacts, especially on screen. This is true not only for the characters but for those viewing the shows. Black people want to be seen in our fullness — and that includes radiant afros, plaits, braids and twists; loc’d styles and bone-straight hair. Which is why Amor Gillie is committed to having a Black hair stylist on the set of her one-hour drama “The Honorable.” (The script was sold in 2019 to CBS and is now at BET.) But even she admits that’s not going to be easy to accomplish for every production.

It’s a matter of, well, grooming.

“And that goes back to the fact that it’s still a union job,” Amor Gillie says, referring to on-set hair stylists, and getting stylists and beauticians [who work with Black hair] on those sets is not easy. A lot of times, these are people who already work in or own a shop. They’re not likely to be industry union members or to work near TV/film sets. To find people who would be willing to come to L.A. or another movie location can be a challenge.

It’s also about getting people who understand the business.

For the aspiring industry stylist, this first means a lot of hustling and oodles of hours shadowing an on-set hair stylist — most often the “key stylist” — and building a portfolio. Those behind the chair are required to perform an infinite variety of ’dos, like period styles or “specialized hair” (which, coincidentally, includes African American hair), stay current on a plethora of products (how hair performs in rain, wind or humidity), work with multiple actors, and meet the demands of the director or showrunner. Shooting days are fast-paced for TV and typically slow on film sets. A starting salary can be up to $77,000. But the hours are often long, and the hair team is usually the first on set and last to leave.

Bell features three actresses with varying horror stories of working with white stylists who could not work with the textures of Black hair.

“It’s different from being in the beauty shop all day laughing and talking,” Amor Gillie says, “If there’s a call time at 7 a.m., then you might have to be ready to work by 3 or 4 in the morning so that the production can be on time. So, it’s going to take looking at how to get people in in a way that would benefit [Black stylists] being in the union, getting the word out that there are opportunities doing hair on sets, and that it’s a viable career.”

In “Defending Our Crowns,” Bell features three actresses with varying horror stories of working with white stylists who could not work with the textures of Black hair, having to wear protective weaves or wigs over their own hair, and being seen as “difficult” when arriving on-set with their hair already salon-styled. Bell, who was a journalism major in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts, was setting up the in-person interviews at an area beauty salon and had charted the places where she would shoot her b-roll.

Then, COVID-19 flipped her script.

“It was hard at first to get through it because I had an idea in my head about what I wanted the film to look like,” Bell admits, citing the plans she had lined up to film her documentary before the shutdown. “I had to schedule the calls via Zoom, and I had to do everything virtually. I was really upset about that because I had the vision in my mind of what I wanted the film to look like, and it wasn’t going to look like that at all.”

But once Bell finished her first interview, she was raring to go. “I felt so good,” she says, the glee resonant in her voice. “I was happy with how the conversation went, and it felt good to be able to share experiences with someone who had similar experiences to my own when it comes to natural hair and embracing your hair. That gave me the momentum to keep going and get through the entire project.”

“Of course, the film would have looked better with in-person interviews,” says Bell’s advisor, Rubén Martínez, Fletcher Jones Chair in Literature and Writing in BCLA and professor of English and Chicano Studies, “but she did so good with the b-roll, the source material and her interview subjects. They were three of the most fabulous speakers — just fantastic — that they could sustain it.”

More than that, Martínez says, Bell’s got that thing. “Just look at the title of her project — ‘Defending Our Crowns’ — the clever appropriation of that phrase from the fighting and sports world. She has top-flight skills in both print and video. It’s clear to me that the journalism program can only take some of the credit here. She has that it thing. She came into the classroom with a very strong skill set.”

“Defending Our Crowns” is a quintessential culmination of Bell’s loves: fashion, beauty, media and wrestling. (Yes, you read that right: wrestling.) Born in Los Angeles and raised in Pontiac, Michigan, she wanted to become a hair stylist like her mother and studied cosmetology at a local trade school while juggling her final two years in high school and dreaming of her chance on the mat.

“I was a super fan of World Wrestling Entertainment, and I was going to be a wrestler,” she says, laughing, “I used to take clips of wrestling from TV and edit them into music videos to create the stories I wanted to see from those characters, or the stories I would want to portray if I were to be a wrestler. At the time I didn’t know I was creating short films, or music videos. I was just creating, and I loved it.”

Before transferring to LMU as a second-year junior, Bell was studying kinesiology at Santa Monica College. “I was definitely on a different path,” she says. “But I had a group of friends [who] would get together on the weekends or after class and shoot little short films and music videos. That’s when I realized I could actually have a career in that.”

Bell honed her journalism skills in classes with Evelyn McDonnell, English professor and former director of the BCLA journalism program, who helped Bell land an internship at The Argonaut, a weekly newspaper serving Marina del Rey, Venice, Santa Monica and the Westside.

“She discovered she could write about fashion and beauty, and that it was a valid pursuit,” McDonnell says. “She’s really interested in making films, so I think she understood how journalism could inform that kind of work.”

Bell’s film has gone on to receive honors from Student Doc L.A., Hollywood First-Time Filmmakers Showcase and the Spotlight Documentary Film Awards. And in April “Defending Our Crowns” was named Student Journalism Best Arts or Entertainment Feature at the Los Angeles Press Club’s National Arts & Entertainment Journalism Awards.

“I was not expecting this to do so well, honestly, because it didn’t turn out the way I wanted it to in the beginning,” she says, with a laugh. “I love the film, and I stand by it 100%. I’m not ashamed of it at all, but I know I can do better, and I want to improve it.”

Bell says she may work to update the film while in graduate school at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. But there are more immediate stories she wants to tell.

“I won a grant from Getty Images to create a short documentary and shoot documentary images,” she says, “so I want to use this grant to fund that project, which will focus on beauty supply stores and the Black hair experience.”

“Now is a great time,” Bell says of being a young filmmaker. “We all have so many fresh stories and ideas, especially within the Black community. Now is a perfect time to be free and share the story you want to hear and the story you want to be told.”

Janice Rhoshalle Littlejohn ’90 is a Los Angeles-based journalist and author. She documented her own natural hair journey in the essay “Growing Gray,” in Ms. Magazine (March 2020). She is the associate director of the L.A. Institute for the Humanities at USC and is working on a documentary about female jazz sax and horn players. Follow her @JaniceRhoshalle.

To view Stephanie Bell’s award-winning documentary “Defending Our Crowns,” go to stephbproductions.com/defendingourcrowns. A behind-the-scenes video of our photo shoot can be viewed here.

Hair styling by Kelsie Lyn. Follow her @KingKelsie.