In our series on The Seven Deadly Sins, Lynell George writes about envy.—The Editor.

I listen for a living — to people and their stories about the world and how they see themselves within it. I carefully catalogue their struggles and dreams, what they feel has passed them by. Desire, the shape and weight of it, figures prominently within many of the personal narratives I collect as a journalist for stories about the human condition. I listen to the words they use to describe their yearnings. It doesn’t matter, I’ve learned, if the teller is a blue-collar laborer, a self-made “guru,” a teacher or activist or someone still seeking: desire — a just-out-of-reach want — propels them further than they expected — and often further still.

Recently, though, I’ve noted an edge, a different quality of longing. In our ever-competitive, goal-focused society, even the language of achievement shifts: Instead of, say, “personal best,” one might now articulate a desire to achieve a pinnacle so as to “outpace” or “outdo.” A different sort of yearning sets in, and it’s far less benign.

What struck me in these self-revelations is the diminishing line separating desire from envy. The former can open you up, the latter shuts you down.

Envy has dogged us for millennia. It has nipped at our hearts; it has clouded our relationship with the here-and-now as it locks our gaze onto an outsized fantasy future. Covetousness can grow out of a series of defeats or frustrations; it can sometimes trace its roots to unacknowledged shame. Envy’s edge keeps us from feeling entirely happy, whole and part of the world. Comparing ourselves in one arena or another appears unavoidable, no matter how centered we pride ourselves in being. We’ve long looked over the proverbial fence, keeping tabs, measuring, especially when we’ve endured emotionally draining personal droughts — financial reversals, layoffs, deaths. As time quickens, we find it more difficult to put the blinders up and stay on our personal path.

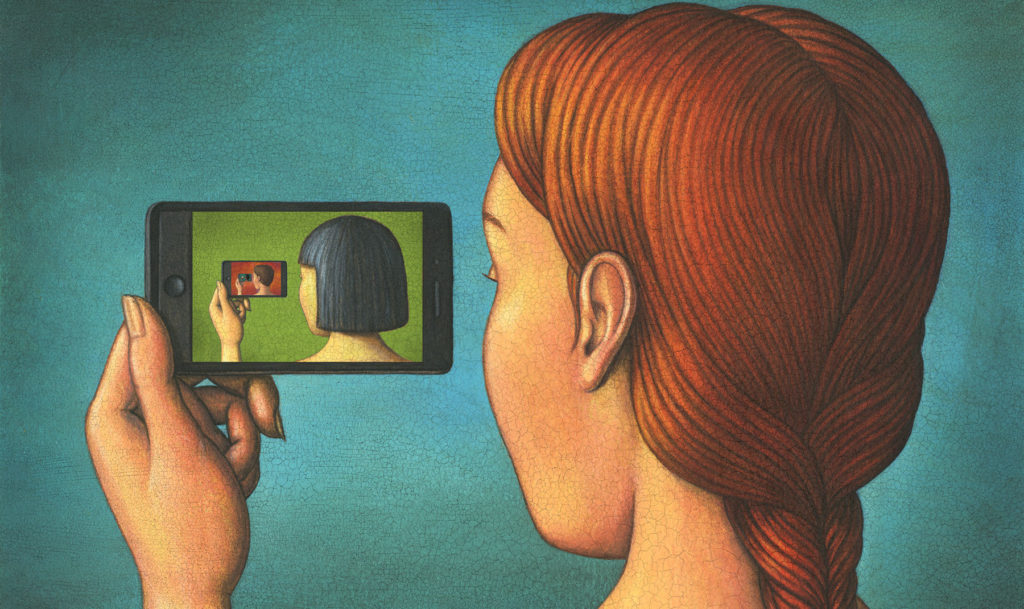

We can ascribe much of this to the evolving theater of our shared stories. What were once considered the personal details of daily life have become a nonstop blur of check-ins, couplings or acquisitions shared both minute-to-minute and globally. Consequently, little is left to our imagination. We have far more access to adjacent lives. More and more, our windows on the world are the numerous screens we tote about daily. These are the portals that look out onto the far-flung lives of family, friends or even past acquaintances, and through them, we can tally their advancements (even in the middle of the night) against our own. Often, with that, envy grows.

Colloquially, envy has entered the language in odd spaces and intervals. The terms “house envy” or “hair envy” or “shoe envy” exemplify how the word has been reduced to branding or lunchtime catch-up chat. (Some of these neologisms elude logic: I’ve scratched my head at a business’ shingle — “Massage Envy” — and wondered at its naming origin.)

This causal usage de-thorns envy and the damage it can visit upon a life, how it can reshape and poison both thought and action.

Envy is as treacherous as it is unavoidable. All too often we’ve discovered it’s raging, full blown, before we’ve realized it was, curled up deep inside, lying in wait.

For all of its “bringing together,” our daily regimen of social media feeds our sense of dislocation. In a study published last year, researchers at Lancaster University examined data drawn from 35,000 participants, between the ages of 15 and 88, from 14 countries. What they learned was that dislocation isn’t caused just by scrolling through Facebook timelines or Instagram feeds but by “rolling over online experiences in our mind long after we’ve logged off.”

Diagnosing these funks as “social media depression” may oversimplify the malaise; however, it helps us to pinpoint why these “windows” trigger wanting and feed at times a debilitating sense of falling short. Envy is a fixation, a myopia that causes blindness to what is actually present. Putting the brakes on covetousness — distortions of what’s meaningful — means finding our vision. That demands taking stock, recalibrating and reordering our values. Ultimately, it requires a focus on what lies within, not without

Lynell George is an L.A.-based journalist and essayist who covers the arts, culture and social issues. A former staff writer for the Los Angeles Times and LA Weekly an“Jumping Time” appeared in the summer 2016 issue of LMU Magazine.

More on The Seven Deadly Sins

Sloth

Words by Susan Straight

Illustration by Sandra Dionisi

Lust

Words by Denise Hamilton ’81

Illustration by Jason Holley

Greed

Words by P-’Dre Heresy

Illustration by Marc Burckhardt

Anger

Words by Brendan Busse, S.J. ’99

Illustration by Sandra Dionisi

Gluttony

Words by Oliver de la Paz ’94

Illustration by Marc Burckhardt

Pride

Words by Jason S. Sexton

Illustration by Sandra Dionisi

Also see Exit Lighting

By Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch

Return to Virtue Reality