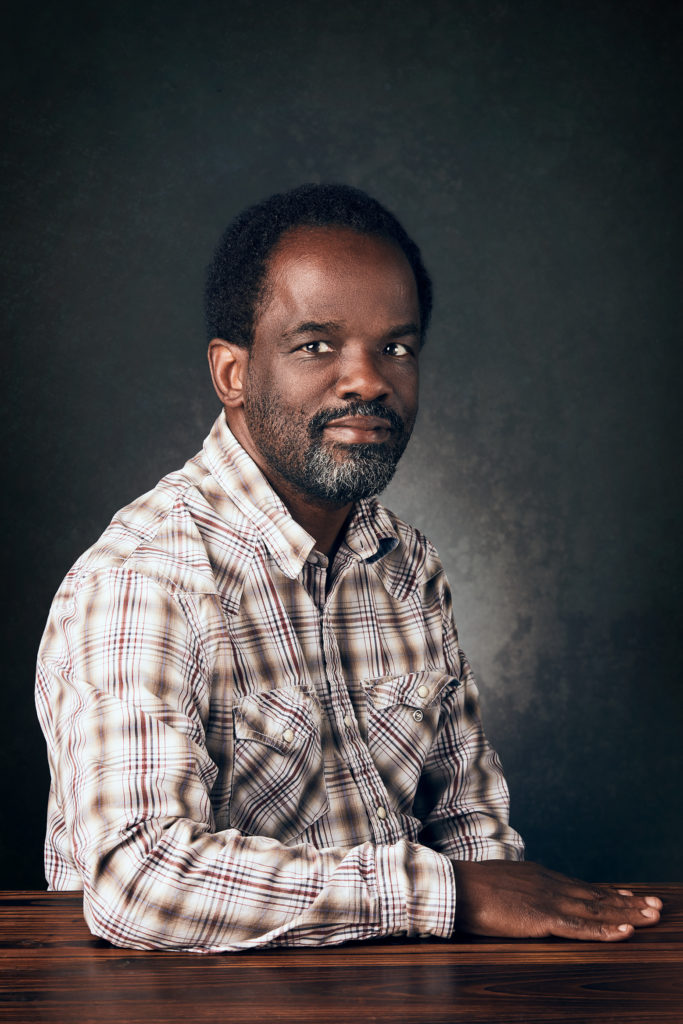

It’s a sunny autumn morning about five miles southeast of Loyola Marymount’s Westchester campus, and Mary Agnes Erlandson ’82 sits on the second floor of a converted mini mall, in an office that once sold auto insurance. A man shouts up from the parking lot below: Sandwiches are here!

Over the next hour and a half, the wiry Erlandson moves like a tornado, shifting through the complex of rooms that look like they once held nail salons or dry cleaners but now — at St. Margaret’s Center in Inglewood — offer various services to the area’s considerable homeless population. One enormous, chilly room, a former flower shop, holds food — not just canned beans but produce, greens, yogurt and eggs. Another room is set aside for psychological counseling. Another is for GED lessons. Yet another is a place where people without a fixed address can pick up mail. Every Thursday, a lawyer comes in to advise renters how to fight eviction. On Friday, portable showers arrive.

“You have to pay attention to the quality of life while people are on the streets,” Erlandson says, “because housing can take months.”

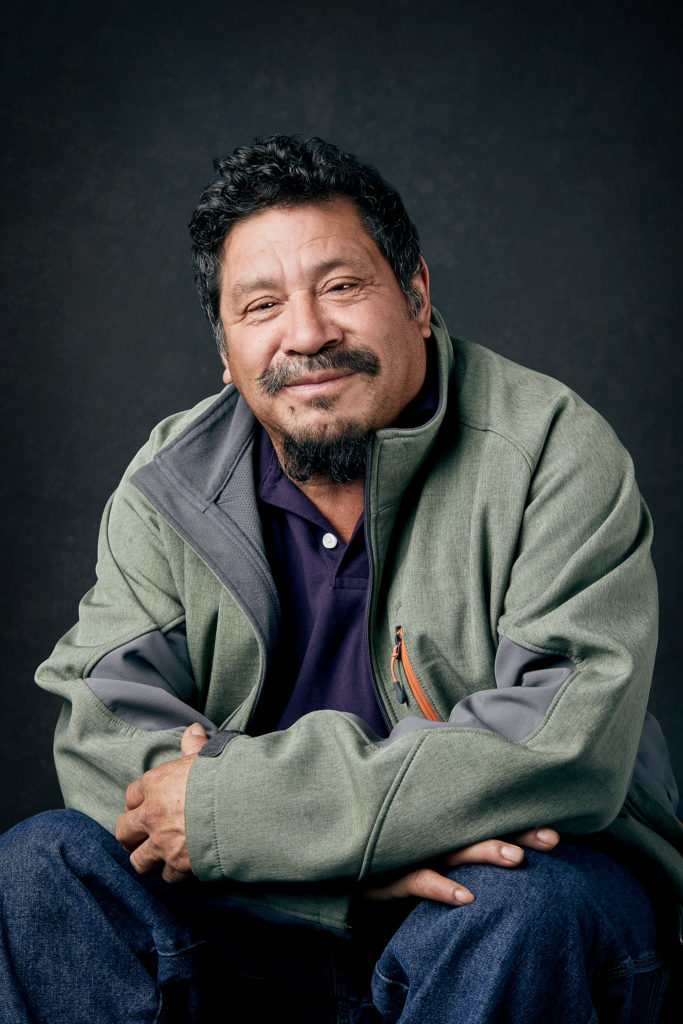

Across town, on a winter Wednesday in MacArthur Park, Tony Brown ’92 is walking through a sprawling, 80-year-old building that offers after-school sports, music and visual arts programs to 500 kids a day in elementary and high school. It’s pouring rain, but Brown remains sunny as he describes the progress he’s made across 16 years helming Heart of Los Angeles (HOLA).

If the nonprofit Erlandson directs, part of Catholic Charities of Los Angeles, aims to address homelessness after people have fallen into it. HOLA is about heading off the paths that can lead there. The kids who come to HOLA — mostly from poor families and many whose housing is insecure — have gone on to Brown, Princeton and Berkeley.

THE TERRITORY OF HOMELESSNESS

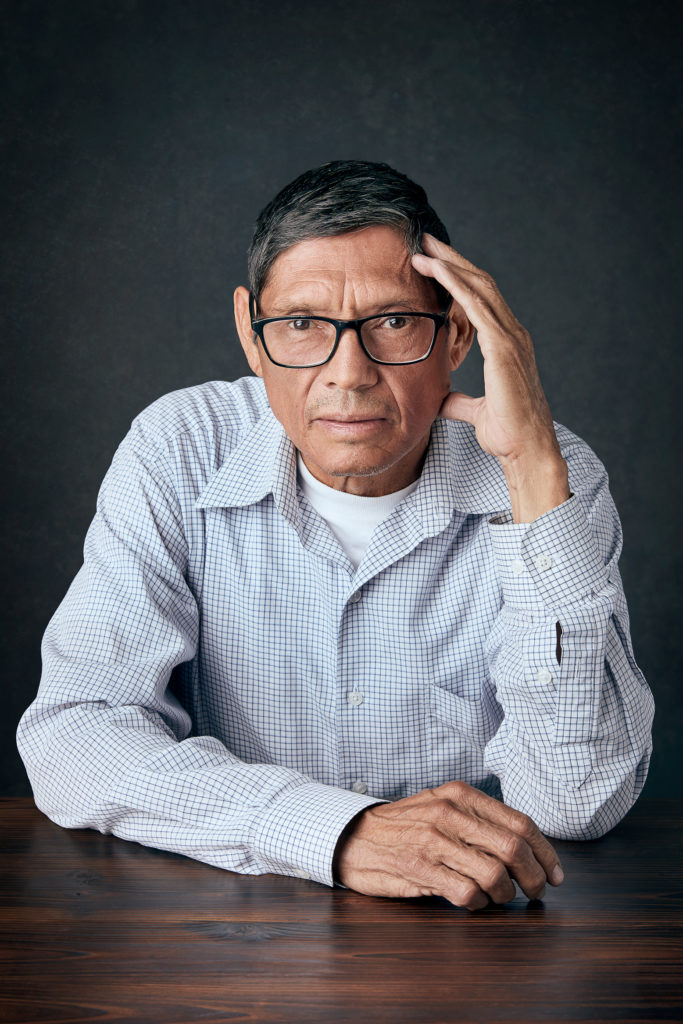

A third place is metaphorical but also real. Novelist L.P. Hartley wrote that the past is a foreign country; Heather Tarleton, professor of health and human sciences in the LMU Frank R. Seaver College of Science and Engineering, thinks of homelessness the same way, but it’s a territory not so foreign for a lot of people. “I really view homelessness as a situational experience people move in and out of,” she says, describing it like a place on a map. “It can be highly dynamic based on how many resources and how much social capital we have. Sometimes we get into that place and can’t get out.”

The flipside of this, though, is that homelessness is not always a life sentence. And there are people working to keep it from being one.

When most people think of homelessness in Los Angeles, they typically picture the encampments on Skid Row, where thousands live in tents and sometimes without them. And indeed, the one-two punch of the Great Recession and the rising cost of living in greater Los Angeles has sent the numbers skyward over the past decade. Camps are no longer limited to downtown L.A. and pockets of Santa Monica or Venice; you see them often alongside freeway offramps and beneath overpasses, in an eerie echo of the Hoovervilles of the 1930s.

Neither have all the services aimed at abating the problem hit their mark: Perhaps a quarter of homeless people are mentally ill, but the state has not always effectively spent funds accumulated from Prop. 63, the Mental Health Services Act that passed in 2004.

Some argue that the problem is deep and systemic and cannot be addressed through uncoordinated action. Jeff Dietrich, a longtime activist who just retired from leadership of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker, comes out of the tradition of radicalism and protest embodied by Dorothy Day, who in Depression-era 1930s New York helped found the Catholic Worker newspaper and a house of hospitality. Dietrich has complained that the dollars are not nearly sufficient even after the city committed new funds in 2015. “Maybe L.A. should just use this paltry $100 million to bring in the Red Cross, install toilets, wash-up facilities, tents and dumpsters, and declare skid row a permanent refugee camp,” he wrote in the Los Angeles Times.

And while the problem is steeper in Los Angeles and California than the rest of the U.S., the crisis is nationwide, with more than a half million homeless across the country.

L.A.’s homeless problem is increasingly part of the political debate and discussed in the media; there’s a sense that it’s reaching crisis proportions, as when the numbers increased to 55,000 people in 2017. (About a quarter of those are in shelters, and more than that in cars.)

But that March, county voters passed Measure H and, combined with a city proposition from 2016, $4.7 billion began to be used to combat homelessness through 2027. And last year, the homeless population went down, for the first time in years — dipping 3% in the county and 5% in the city of L.A. (Veteran homelessness decreased 18%.)

Erlandson, daughter of a former LMU dean and English professor, has been in the game for more than 30 years and knows how structural the problem is. But she feels things turning a corner. It takes more than money, but funding allows for food, shelter, staffing at agencies and training of the next generation of people like her. “I feel like the silent majority is people who approve of services and are supportive of initiatives, even when [those initiatives] hit their pocketbooks.”

THE END OF BLAME

As do many others working in the homeless-relief world, Erlandson sees hope here. Part of what inspires that is the changing public perception. “There was a lot of blame in the past — especially if there was drugs and alcohol,” she says. “A lot of judgment.” Now the general public tends to understand the roots go beyond personal irresponsibility: “People have experienced trauma, and this is how they responded to it. It’s breakups, divorce, losing a job — a lot of people who never thought they’d have to think about homelessness.”

Research shows that nearly half of people homeless for the first time were there because of a job loss. About 6% are homeless because of domestic violence and 15% because of substance abuse.

Tarleton still sees myths, and not just among the undergraduates she teaches. As a society, she says, we don’t focus on the root causes, which she deems as de-institutionalization during Ronald Reagan’s governorship, tattered veterans services and foster-child programs, and a full-blown housing shortage. “The solutions are sort of patches here and there; there’s not really a county-driven effort though you have some good nonprofits.”

Partly to combat misperceptions, Tarleton took students in a Health and Human Sciences course into three days of simulated homelessness, each with only a backpack, relying mostly on their own feet and public buses and, once their food ran out, soup kitchens. They slept outdoors on campus and at a shelter. She compares the conditions to the way many Americans lived in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before running water, sanitation and waste disposal were widespread.

“By the end,” she says, “they were just broken.” And these were mostly healthy children of privilege. “However you come into it, homelessness deepens any problems you already have. And the longer you’re in it, the worse it gets.” The experience gave the students an understanding deeper than a textbook and led two to start a research project on the physical impact of homelessness.

HOLA sits in one of the city’s oldest, densest and poorest areas, but it’s more than just an oasis: For a lot of the kids, it’s a portal to a better, safer world, and not just for the time they’re inside.

One of Brown’s guiding principles is that children become different people if they are put in situations that bring out their best qualities and discourage their worst. Growing up a black kid in primarily white Sierra Madre, with remnants of Jim Crow, Brown had a family that encouraged him as a competitive swimmer and as a choral singer in the local Catholic church. “You just needed to put me in the right environment to excel,” he says. “I don’t just believe that, I’m seeing that — we’re proving it.” Nobody, he says, has “set these kids up for success in the arts or in athletics. So HOLA is there to fill that gap.”

But even there, the homeless problem can creep in, like the rain that swamps in through HOLA’s doors and windows: Whether it’s the encampments that sometimes line nearby streets, older brothers who end up sleeping rough, rising rents that push families from one-bedroom apartments to sharing studios with others or kids couch surfing for weeks at a time, the issue is rarely distant.

HOUSING INSECURITY

Homelessness, and the adjacent phenomenon known as housing insecurity, is complicated and layered. It’s woven in with mental health, landlord-tenant law, the legacy of racism, cycles of poverty, taxation, defensive NIMBYism, the unstable gig economy, public policy, urban gentrification, and the real-estate market. (It’s as complex as the rumored figure of a man with two vans, one he sleeps in and one he uses to repair TVs.) The solutions, as a result, need to be equally varied and multitiered. In a country with a thinner safety net than most of the developed world, the homeless, like the poor, will always be with us. But each of the three figures from LMU sees possibilities here.

While nothing guarantees against homelessness or poverty, Brown is pleased to see a change among the families he works with: These days, across every ethnic and racial group, they understand the value of education and the importance of sending their kids to college, and the nonprofits he teams with support the push.

Tarleton is relieved to see the homeless-relief community concentrating on mental and physical health. She calls it “a significant shift away from the PB&J sandwich handout model.”

Erlandson, who manages to be intensely energetic and serene at the same time, feels a new dynamism coming into the relief community as public opinion and funding open up. “There are all these brilliant ideas coming up now,” she says. “New ways of addressing the problem.”

Scott Timberg, a frequent contributor to LMU Magazine, is the author of “Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class.” He has written for The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, Los Angeles Magazine and elsewhere. Follow him @TheMisreadCity.

This article appeared in the spring 2019 issue (Vol. 9, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.