“The Hunger Games,” in film as well as in print, has ignited the heart and imagination of millions across the globe with its vision of a violent, authoritarian government that wages war against its people. Francis Lawrence ’91, director of “Mockingjay – Part 2,” discussed with critic David L. Ulin the fictional dystopia whose political conflict mirrors struggles taking place in the world today.—The Editor.

Francis Lawrence ’91 seems preternaturally calm. Sure, he’s directed one of the most anticipated movies of the autumn — “The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2,” with a budget of $125 million and a cast including Jennifer Lawrence, Donald Sutherland and the late Philip Seymour Hoffman. But on a Wednesday afternoon in mid-September, the 44-year-old director sits in a nondescript office in West Los Angeles, gray hair combed back off his forehead, chatting amiably about where he’s going and where he’s been, a demeanor so relaxed you’d never know he had anything at stake. “Mockingjay – Part 2” is, for all intents and purposes, finished, nothing left to add but some effects, and Lawrence is enjoying this respite between the making of the film and its release just before Thanksgiving.

Partly, this has to do with the fact that he has been here before: “Mockingjay – Part 2” is the third “Hunger Games” film Lawrence has done. He was brought in for the second movie, “Catching Fire,” and wasn’t sure, initially, whether he wanted to take on a sequel to a film he hadn’t made.

“A huge part of thinking about whether to take the job, or even to have any meetings,” he explains, in a quiet voice laced with a soft Southern California twang, “was whether I felt there was enough room for me to grow the aesthetic, grow the world, grow the stories, all of that.”

This is an important question, perhaps the most important, because “The Hunger Games” comes with a legacy all its own. Based on the trilogy of young adult novels by Suzanne Collins — which together have sold more than 65 million copies — it was a publishing phenomenon before the first book was ever developed for the screen, with all the complications that implies: rabid fans, high studio expectations and the necessity to create a set of adaptations that are faithful to the originals yet stand independently. For Lawrence, that was a challenge but also an appeal.

“The books,” Lawrence says, “explore some relevant, timely themes. … There’s war, the consequences of war and violence; we’ve had war since the beginning of mankind. Then, there’s propaganda, media manipulation and the use of celebrity.”

“I had already read the series,” he recalls. “And the first movie is just the beginning — the beginning in the story but also of the thematic material. So that was really exciting, the idea of starting to explore the more thematic material the books had to offer.” Lawrence also realized the second film, though it would inherit a cast and a few aesthetic choices, could take the story to new places — further develop the Capitol, for example. “There was a lot of room to create, room to move,” Lawrence says.

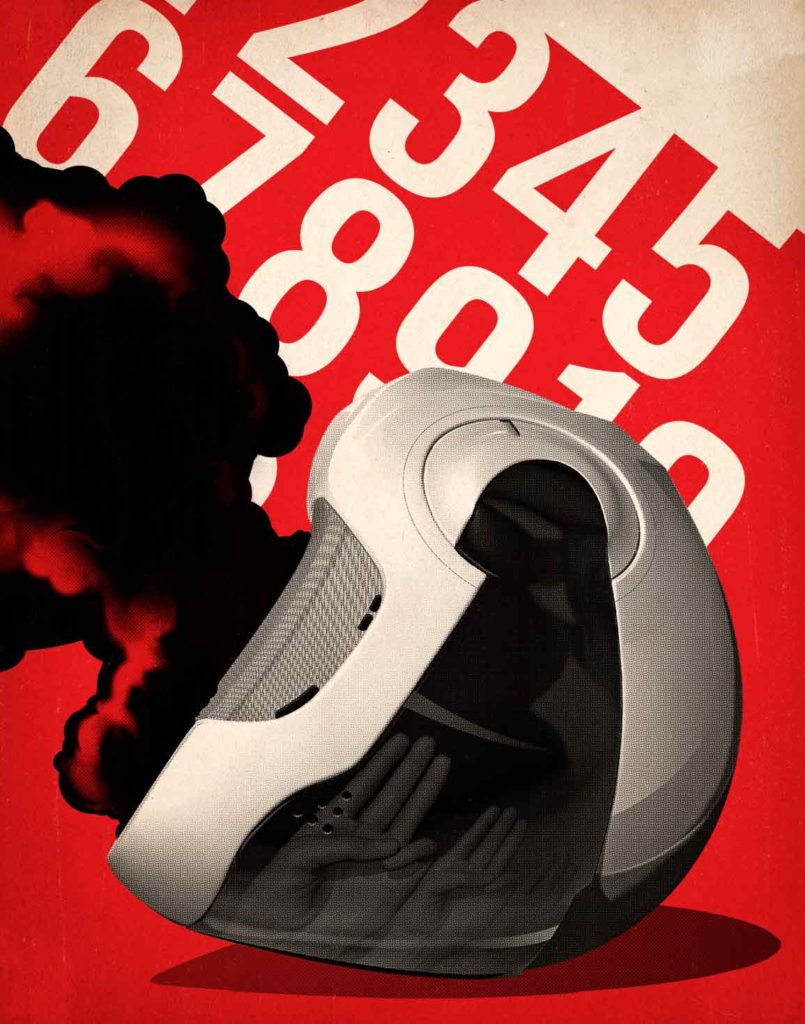

The thematic material, to be sure, is a key component of the novels, which, like the movies, take place in the nation-state of Panem, where society relies on a televised gladiator competition (the Hunger Games of the title) to keep its masses pacified. Such antecedents are intentional. Collins has acknowledged being influenced by classical history and myth. One inspiration was the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, with the labyrinth as precursor to the arena where the games take place. The saga also satirizes celebrity culture — in particular, reality TV.

“The books,” Lawrence says, “explore some relevant, timely themes. And some of them, unfortunately, are timeless themes as well. There’s war, the consequences of war and violence; we’ve had war since the beginning of mankind. Then, there’s propaganda, media manipulation and the use of celebrity.” That’s a potent and timely mix, now that the border between reality and illusion has been blurred, irrevocably, by digital media and the entertainment complex. “It’s rare,” the director adds, “to find something this popular that actually has some meaning to it and something to say.”

The balance — or tension, perhaps — Lawrence is addressing has led to some unexpected resonances. In Thailand in 2014, seven anti-government protestors were arrested for flashing the three-finger salute that signifies the rebellion in the films and novels. That same year, a slogan from “Mockingjay – Part 1” — “If we burn, you burn with us” — was graffitied on an arch in St. Louis in the aftermath of the unrest in Ferguson.

“It’s kind of strange,” Lawrence murmurs, as if searching for an explanation. “Ideas that Suzanne has written about, that are connecting with people, are now coming back out the other end, so it’s art imitating life being imitated by life again.” Such an interplay, however, comes with responsibility. “It’s exciting,” he elaborates, “because you know the reach of the movies and you hope the movies can make people think, and give people hope, ideas. The scary thing, though, is that kids are doing the salute and getting arrested. You’re seeing ‘If we burn, you burn with us’ and thinking, people could die, get hurt or go to jail.”

In a piece published late last year in Salon, Sonia Saraiya pointed out that although “The Hunger Games” may depict a dystopian fantasy world, we witness a version of it when we turn on our own televisions: a “struggle between those without power and those who are eager to hold onto their own.”

That’s the essence of Collins’ saga and the movies it has inspired. And yet, where is the line between entertainment and activism? For Lawrence, the mix of confrontation and complicity is the draw of the material, that just by playing the Hunger Games, one is (must be) compromised. Even in the arena, one has to seek allies — all of whom will ultimately be betrayed. “The sides are never black and white,” Lawrence says, “and it’s not always clear who is good and who is bad. People need to think for themselves.”

Thinking for oneself, of course, is also the requirement of the storyteller, whether Collins working on her books or Lawrence turning them into films. His own trajectory offers a case in point, an example of how one builds a career.

For Lawrence, the mix of confrontation and complicity is the draw of the material, that just by playing the Hunger Games, one is (must be) compromised.

While still an undergraduate at LMU, he turned an internship into an assistant director gig on the 1993 feature “Marching Out of Time.” Then, he went on to direct music videos for a decade or more. His first film, “Constantine,” came out in 2005; he also directed “I Am Legend” and “Water for Elephants.” The lineage is unlikely, from videos to features — with forays into television. But for Lawrence, the forms, or at least the making of them, are more related than they may appear.

“I never intended on making music videos,” he admits. “But I always wanted to tell stories and make movies, and the music video thing was new and exciting, and it was this whole new world I fell into.” His first project, a $3,000 video for an indie band, came about with the help of a friend who “still had a student ID so he could get the equipment from Loyola; we begged, borrowed and stole to make these videos.” Within a decade, he was working with Jennifer Lopez, Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson — invaluable experience when it came time to direct his first feature film.

“Graduating from college,” he laughs, “I would have said I was ready to make a movie. There’s no way in hell I was ready to make a movie … but I had close to 300 shoot days under my belt. Being on set, working the crew, working with schedules, dealing with some outrageous personalities, shooting in different countries, states and environments, all kinds of effects — I had done it all before.”

What Lawrence is describing is experience, which is essential to any creative life. This, he suggests, was also the benefit of film school, “to be in the bubble of film, around film people, to have access to the equipment needed, the opportunity to make movies.” It’s different now, he says, reflecting on a world where kids can shoot films on their phones and edit on their laptops. But the imperative is the same. “Just make,” he insists. “Kids can be out there every weekend making movies. Ninety-nine percent of those movies are going to suck — I know mine did — but you have to get that out of your system. You have to copy movies you like and fail. You have to go out and shoot and shoot and shoot. You have to practice every weekend, and redo it when it doesn’t work.”

If, in one sense, Lawrence is offering advice to students, in another, he is talking about himself. It’s a long road to developing a vision, an aesthetic; it’s a long road to a creative life. “Creatively,” he says, “there should be almost a bubble. You have a vision, and you want to get it. You get the best people around you, and you go for it.” This is, of course, what he is after now.

What is the lure of “The Hunger Games”? It’s always dangerous to quantify a phenomenon, but perhaps we can agree that it begins with vision, a sensibility about the world. That world can be invented, as is Panem, but it must connect back to an elemental core. Or, as Lawrence puts it: “What makes it interesting is that Suzanne is writing stories based on themes that have been around forever. That’s what makes them resonate.”

David L. Ulin is book critic of the Los Angeles Times. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the author or editor of nine books, including “Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles,” the novella “Labyrinth” and the Library of America’s “Writing Los Angeles: A Literary Anthology,” which won a 2002 California Book Award.

This article appeared in the winter 2015 issue (Vol. 6, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.