If film studios have a recipe for gore, slasher and horror movies, violence may be the main ingredient, and more of it is usually considered better. But for Mark Evan Schwartz, some of the most effective uses of violence depend on the viewer’s imagination.

Schwartz, an LMU faculty member since 2000, is associate dean of the School of Film and Television and professor of screenwriting. He has written more than a dozen feature films, television shows and TV movies, and is the author of “How to Write: A Screenplay” (second edition). Schwartz fell in love with films as a teenager when he saw Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch.” He watched it repeatedly to understand how the film was made, shot and edited. Schwartz was interviewed by writer Christelyn D. Karazin ’99 and Joseph Wakelee-Lynch. This is an extended version of the interview published in the fall 2010 issue of LMU Magazine.

In the late ’60s and ’70s, films such as “A Clockwork Orange,” “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Wild Bunch” shocked and outraged people with their violence. Are films more violent today than they used to be?

While I think the amount of violence has been relatively constant, violence has probably become more graphic in part because it has become more graphic on television, particularly with the advent of cable TV. Feature films have to raise the bar a little higher to get people out of their houses and into the theater.

What does that mean for today’s screenwriter compared with one in the ’60s?

Today’s audience expects violence on the screen to look different than in the ’60s. So a screenplay that is submitted into the system more often than not will be passed on if the film is considered too soft. The writer who is writing with violence in mind has to understand that the audience does not want something that is soft.

When a screenplay is submitted, is it evaluated for whether it’s too soft as well as whether it’s a good story?

Yes, both. But if you’re writing an action film and the violence is on par with what’s on TV, then there’s no reason to leave the house to see the movie. Conversations often take place about “How can we raise the bar? How can we make it more intense, more graphic, more startling, more exciting? How can we build a bigger roller coaster ride?”

Then how do gore, slasher and horror movies fit into this picture?

Well, when you’re talking gore, it really goes back to the low-budget exploitation films of the ’50s, which mostly targeted teen audiences looking for cheap thrills. Then, in 1960, Hitchcock made what was essentially the first mainstream slasher, “Psycho.” Mature audiences flocked to see it, not just because of the thrill, but because they were seeing an engrossing, well-told story with depth of character, a moralistic point of view and real cinematic brilliance. It raised the bar, telling the studios there was an audience for this type of film well beyond kids. To reach that audience and hold onto it, they had to continue to raise the bar.

Is there a difference between the use of violence in gore movies and in horror movies?

While gore suggests, and even requires, extreme violence, horror as a genre doesn’t. The best horror, in my opinion, is more a matter of atmosphere than violence. One of the most terrifying movies I’ve ever seen is Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby,” a masterpiece. There’s very little, if any, violence in the film. The implication of violence happens off screen.

About Hitchcock, “Psycho” and “The Birds” are remembered as psychological thrillers, not for their violence. Why don’t we think of them as violent?

That’s an interesting question. I certainly think of them as violent. In “Psycho,” Janet Leigh’s character is set up as the protagonist. We become emotionally invested in the character, only to have the rug pulled out from under us: We see her horrifically killed at the end of the first act. That was considered one of the most shocking and graphically violent sequences ever put on film.

One great difference between Hitchcock’s movies and today’s slasher films — and “Psycho” was one of the pioneers of the genre — is [restraint]. We never see the knife make contact with the character’s flesh in “Psycho.” The actual stabbing is left to the imagination. In contrast, today’s slasher films are intensely graphic, leaving virtually nothing to the imagination.

In “The Birds,” imagination comes in again. At the end, we’re left hanging with a feeling of uncertainty, because the family drives off — in a convertible of all things. There was a climatic sequence that Hitchcock was going to film, but the budget ran out. The studio was uncertain about continuing the investment in the movie because no one had ever made a movie like this before. They weren’t sure how the audience was going to respond to it. So, the studio just released it with its unusual ending, and “The Birds” came to be known for one of the great film endings.

What do you teach students in your classes about using violence in screenplays?

I’m an advocate for responsible violence in film. A good, dramatic storyteller shows the consequence of the violence. In other words, there are residual effects; it hurts. People who commit violent acts get their just desserts. Or if they don’t, there’s a moralistic implication. It’s important to reveal the consequences.

But how do you teach that? Do students turn in to you scripts or scenes that you return with notes like “Not enough violence” or “This character needs to die here”?

I don’t think I’ve ever written notes that say that! What I have said is that a choice is too soft. If a student is writing an action story and describes an act of violence that I believe is too soft, I’ll tell the student to up the level, that the act should be more graphic, perhaps, or startling.

I’ll also ask about the consequence of the violence and what motivated it. Perhaps it isn’t motivated because a character is psychotic or sociopathic, and that’s what’s startling. I find violence disturbing when it is without consequence. I don’t find that to be good storytelling, because in real life, while violence may appear to have no motivation, there’s always consequence.

What do you teach students about the relationship of a film screenplay to the film?

A screenplay is ultimately a blueprint for a movie. A screenplay is not a stand-alone work of literature. It’s part of something much bigger. Just as with any blueprint, for building a house for example, there are a lot of conversations about what the house will look like as well as what goes into the house. It’s very much the same thing when you’re constructing a screenplay. You want to know that there are elements in place of the story, everything from character to dialogue and plotting, that all fit together. The single most important element is structure: the progression of the story from beginning to middle to end, where certain plot points may hit, and where certain reversals, or turning points, take place.

I want to ask you about a scene of violence, a reversal, in “The Godfather.” Michael Corleone goes to a small, Italian restaurant under the pretense of making peace between his and a rival family. But his plan is to kill the head of the other family and police chief who is on his rival’s payroll. It’s hard to think of another scene in which one act of violence drives a character’s development so clearly, dramatically and concisely. Everything changes in “The Godfather” with that scene.

Yes, it does. That scene presents the great tragedy of the story. Of Don Corleone’s three sons, Fredo is not very bright and Sonny is a live-wire prone to violence. Michael, however, has gone to college and served in the war as a hero. He’s marrying a whitebread schoolteacher. He’s the one who is living the father’s dream of assimilation, everything his father has worked for. But Don Corleone’s worst nightmare comes true: For the honor of the family, Michael kills. Michael pays for the sins of his father.

I think it is truly one of the most vivid moments of violence in the history of film, and there is a consequence to the violence, which you see at the resolution of “The Godfather, Part II.” Michael is sitting alone outside his house, as his father often did. He’s reflecting on his youth, when he intended to not go into the family business. But now his features are hard, and his eyes are dark and cold. His wife has left him, he barely sees his children and he’s just ordered a hit on his brother. At the end of the story, he’s alone and completely morally bankrupt. He has, in fact, lost everything. It’s an amazing story. It’s Shakespearean.

Let’s talk about Clint Eastwood’s “Unforgiven,” a morality lesson on violence if there ever was one.

“Unforgiven,” ultimately, is about how in later years we confront our legacy. And here is a man, William Munny — played by Clint Eastwood — whose legacy was violence. In order to make that story credible, you have to create a violent film. I think “Unforgiven” is a masterpiece.

“Unforgiven” is interesting for another reason. Years ago, the film’s screenplay, written by David Peoples, one of our great screenwriters, began making the rounds. He wrote “Blade Runner,” which put him on the map. The screenplay did not make the rounds with the title “Unforgiven.” The original title was “The Cut Whore Killings,” a very violent title.

Peoples’ screenplay was acquired by a couple of different people, including, as I recall, Francis Ford Coppola, who were unable to get the movie made. Clint Eastwood purchased the script himself and sat on it for years, because he felt he was too young to play the leading character. He saw this as a vehicle for himself, but didn’t feel he could credibly play the part until he got older.

People have debated for a long time the impact of film violence on viewers. How does writing violence affect the writer?

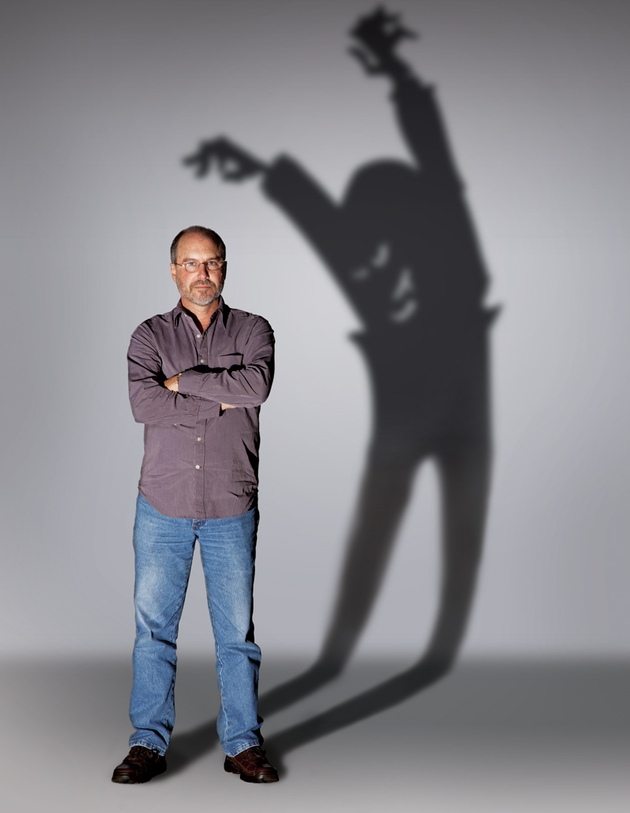

Many of the writers that I’ve known who have written violent material are also some of the gentlest, most thoughtful people that I’ve known. I think you can separate the two. The writer is forced to use his imagination; that’s ultimately the biggest tool the writer has. It can be very cathartic to move the imagination in that direction. It’s also very safe, because the emotionally stable writer knows that he or she is performing a function of the imagination. Frankly, it can be very exciting to go there.

You’ve written films with violence yourself. Do you have nightmares?

What’s interesting most to me about that question is not necessarily the nightmares, although I do occasionally have them. When I’m stuck or blocked, I find that the only way to resolve it is by taking a nap. It allows the brain to go to that place of the unconscious. Almost always, I come up with a solution.

Nightmares are also a product of the imagination. Because screenwriting is very visual writing, I suspect that you go to similar places in the brain to summon it. When you’re writing, it’s a conscious effort. When you’re dreaming, it’s an unconscious effort. I certainly often dream what I’m writing about.

Editor’s Note: As of July 2023, Mark Evan Schwartz is associate professor of screenwriting in the LMU School of Film and Television. In fall semester 2023, he will be teaching at the Budapest Film Academy in Budapest, Hungary.