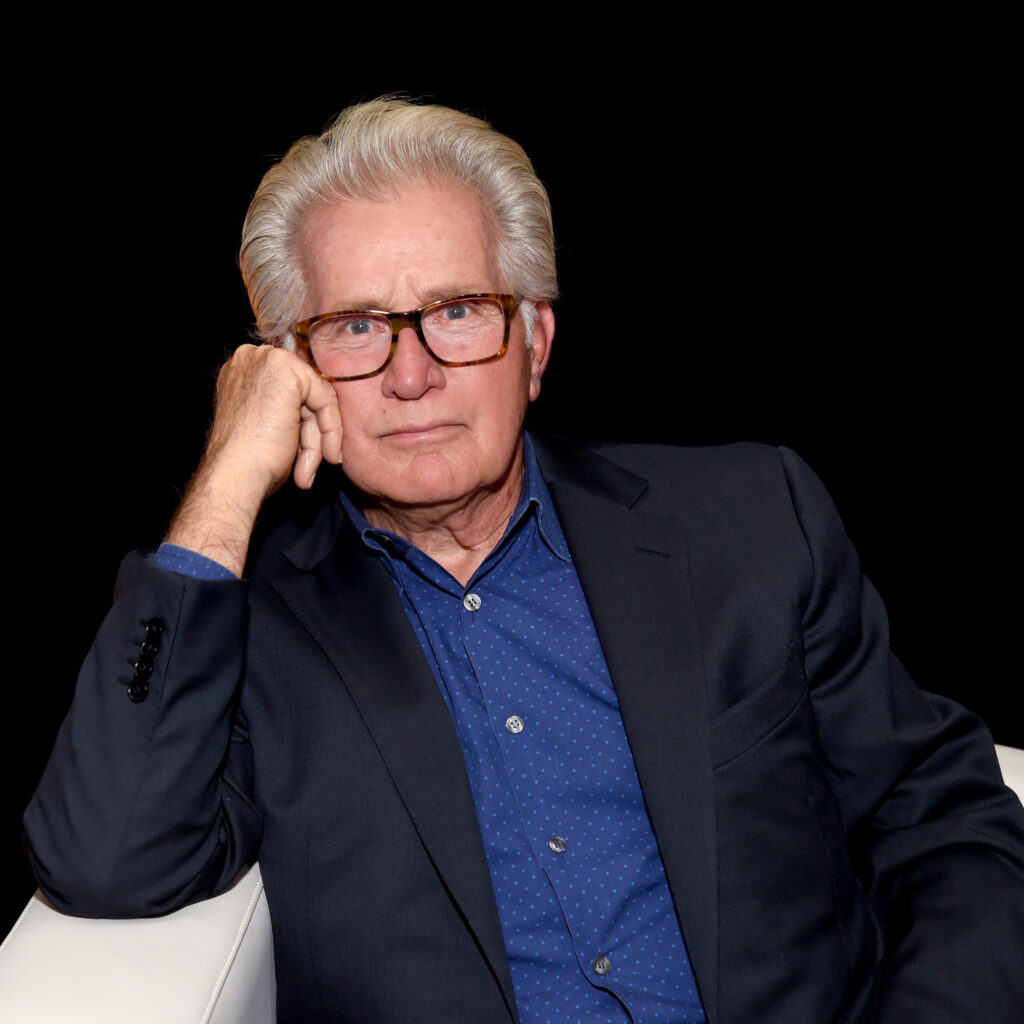

Martin Sheen, who will be the featured speaker at LMU’s Undergraduate Commencement Exercises on May 6, 2023, is recognized as an actor long dedicated to his craft and an activist devoutly committed to his Catholic faith.

His is a career with many film highlights, with roles in “Badlands,” “Apocalypse Now,” “The American President,” “Gandhi,” “Wall Street,” “Bobby” and “The Way,” to name a few. He has established an equally strong presence in television, with guest roles in “Grace and Frankie,” “Murphy Brown” and “Two and a Half Men.” And, of course, Sheen made President Josiah Bartlet, his character in the “The West Wing,” so believable and principled that many fans would have voted for him if Bartlet had been real and had run for president.

A son of immigrant parents, Sheen’s family shaped him, as did their struggles. His Catholic faith is one of his most defining characteristics. With Catholicism as his foundation, Sheen has been devoted to causes of social justice, from helping homeless people to ending poverty, supporting farmworkers and opposing nuclear weapons. He has participated in civil disobedience and been arrested more than 60 times while championing causes that he supports, many with fellow Catholic activists. Sheen was interviewed by Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch. This interview was edited for clarity and length.

The film you starred in with your son, Emilio Estevez, “The Way,” will be re-released in May. In the film, your character’s son dies while on the religious pilgrimage across Spain known as El Camino de Santiago. Your character decides to complete his son’s journey, which changes him. Did making a film about the Camino change you as a person?

It did in ways I wasn’t prepared for. It confirmed more than changed over the period of filming. The most rewarding part about it was the effect that it had on so many people who were inspired by the film to do the Camino themselves. That’s been the most satisfying feeling — the inspiration it gave to so many people. We still hear from people who have done the Camino because of the film and have had their lives changed.

It is, frankly, the most rewarding experience I’ve ever had in my career — stage, TV, movies, whatever. It’s just a deeply, deeply satisfying experience, and a confirmation of how blessed it is to do something honest, something compassionate, something about celebrating our brokenness. We’re all struggling with the same problems in the same ways, and the only way we can really get through life is with each other and form community. That’s really what the movie is about. It’s about forming community. Tom, my character, was not interested in anybody joining him. He had a mission, and that was it. He kept running into silly people, and he couldn’t bear them. And then he realized when he exposed his brokenness and his humanity that they came to his aid to help him heal, to embrace him. I think the movie is about forming community against ourselves, against our devils. The things that keep us apart are the things that will heal us.

You’re committed to movements for justice: supporting unions, nonviolence, immigration, helping homeless people. You’ve been arrested in civil disobedience actions related to causes you care about more than 60 times. Do you ever feel that being an activist on one hand and being an actor on the other are two distinct roles? Or do you think you’ve managed to keep them integrated?

I can’t really separate myself from any of the issues. The issues are not separate, they’re all connected. They’re all joined at the hip by injustice, by indifference. Whether it’s nuclearism or homelessness, there is a connection because the poor are robbed continuously by our insatiable appetite for power and weapons. Not just nuclear weapons, which are the worst and useless: They can’t be used because that’s suicide. The U.S. is the police force of the world. Sometimes it’s a good thing, but more often than not the innocent people are the ones who suffer the most. 53% of our budget is for the military. We’ve left 47% of what the government takes in for the most important needs of the people — health care, housing, education. All of those issues are second to arms and the maintenance of weapons.

I learned that if what you believe is not costly then you’re left to question its value.

Where does your commitment to working for justice come from? Your parents were immigrants: your father from Spain and your mother from Ireland. Did you get it from them?

Both of my parents were very outspoken. They were very committed and very interested in what was going on. They both had civil wars in their countries after they left their homes, and those wars affected their families. Several of my father’s brothers fought against Generalissimo Francisco Franco in Spain. One was in prison for a while. He was forbidden from getting a passport. My dad came here with one brother. Well, he first had to go to Cuba because there was a quota on [the immigration of Spaniards] because of the Spanish-American War. He and his brother worked in the sugar cane fields and came into the U.S. through Miami. My dad worked his way to Dayton and got a job with the National Cash Register Co., which was headquartered there. He worked there for 47 years and met my mother in citizenship school. She taught him English. He spoke Spanish, Portuguese and Italian. She spoke English and Gaelic. She had to leave Ireland after the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and the start of the civil war there. She was 18 years old and came to Dayton in 1921. The civil war ended in 1923, but by then she had already met the “Spannard,” as she called him.

My mother had 12 pregnancies, and nine boys and one girl survived. She died in 1951, and my dad was left to raise all of us. Two were already out of the house, but most of us were home. So, I saw life from that angle. I started caddying at a very exclusive country club in Dayton. I was 9, and all my brothers had done that. It was expected of you to chip in. We went to a Catholic high school and paid our own tuition from the money we earned from caddying. In 1954, I started a caddy union. I got fired. It was the first time I heard, “You’re on private property,” even though I had been working there for five years. It was a wonderful experience in the long run, because I learned that if what you believe is not costly then you’re left to question its value. So, I always knew that the costly things were the most important.

But, mind you, I never had any illusions about changing anyone’s mind, or bringing anyone to my side or my thinking. I learned that very early on when protesting publicly with Dan Berrigan, S.J., who would say, “Don’t expect anyone to be enlightened, moved or inspired by what you do. You don’t look right or left to see if anyone’s following you.” It’s not for us to calculate or count on anybody joining us or being changed in any way. In fact, the only one I’m aware of being changed by what I’ve done is myself.

So, do we act regardless of whether we persuade, or do we put all our effort into communicating why we’re taking action in order to be understood and persuade?

I think you act because you cannot not act. My first arrest, while protesting President Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars initiative, was the happiest day of my life in a way, because I had done what I could to try to prevent a nuclear catastrophe. I had no way of knowing if it made any impression. I knew that at least on that issue on that day, at that time, I did what I could, and I did it nonviolently. I protested joyfully, as a matter of fact, and took whatever came with it.

Let me ask about the TV show “The West Wing.” How much influence did you have on President Bartlet’s spirituality, or was his faith written into the character by Aaron Sorkin and the writers?

It’s hard to know how much influence I had, but I wasn’t tasked by accident: They knew what they were dealing with. When we did the pilot, I had agreed to play the part, but it wasn’t a leading part. It was a featured part. The show was not about the president or the first family, it was about the staff. I was asked to sign on for four to five episodes in the first season, and I would only come in occasionally. The only thing they required of me was that I would not play another president while the show was in production.

I loved the script and had worked with Aaron on the film “The American President.” We had a very good relationship. Bartlet was going to be a Black president at first. Sidney Poitier was first choice, and James Earl Jones was the second choice. Both of them turned it down. But when NBC saw the pilot, they said they should invest more time in the person who was going to occupy the president’s office. So, they came to me and asked, “Would you join us for all 22 episodes?” I said of course.

The only thing I asked for was that Bartlet be Catholic, because I wanted him to have a moral frame of reference on every issue, every personal relationship and every part of his life. Not just his decisions as president but his family, his friends, his staff, his country. They agreed to that, and then I said, “I want a Notre Dame degree.” And they said, “Ok, fine.”

Much of the character was already in place: He was a pretty decent guy, a very clever politician, he was morally sound. But there were episodes in which I disagreed with what he was doing. For example, the episode about the death penalty: I had the power to stop an execution of a criminal who committed a federal crime. I said, “No, I would have to save his life, I would have to give a stay and stop the execution.” Someone told me, “Yeah, you would, Martin, but President Bartlet would not. He’s a politician, and he’s calculating all the angles.” There were a few of those occasions, not many, but it was hard to do sometimes. I often said that when I did things my way, it was Martin; when I did things Aaron Sorkin’s way, it was Bartlet.

That reminds me of a scene that took place in the Washington National Cathedral, after the death of Mrs. Landingham, the president’s assistant. When the funeral ends, President Bartlet has everyone leave the cathedral, then he curses God in Latin for taking Mrs. Landingham from him. I assume that with your having attended Catholic high school, you knew Latin.

Yes, I was an altar boy, and I knew the Latin of Mass very well.

Well, when I watched that scene, my breath was taken away not by Bartlet’s words but by what he does. President Bartlet takes out a cigarette, lights it, draws a few puffs and then grinds the stub into the floor of the cathedral. To me, that was nearly sacrilegious, more so than cursing at God in Latin, almost as if Bartlet was renouncing his faith. Was that hard to do, not for President Bartlet but for Martin Sheen?

That was one of the most difficult things! I stopped smoking twice during the run of the series. I was not smoking at the start. Cesar Chavez got me to stop smoking in the ’80s, and I was always proud of that. I only had to take a few puffs in the episode, but when you have to do it over and over again to shoot the scene, it’s like smoking a pack.

That was one of those moments where it wasn’t me, I had to surrender to the character. The rage was the rage many of us feel toward injustice: How could God let this happen? How could God let this happen to me? It’s deeply human. It’s part of our brokenness. It’s like a child raging at their parents: “How could you leave me at the bus station? How could you not protect me?” That’s what it was, directed to God.

There were two things that made that scene possible for me to know how to play it. One, he chose Latin because he said that was God’s language. Well, I didn’t know God spoke Latin! But I knew the Latin Mass, so that I cherished.

So, I got the Latin down, but how to do the scene? I went to see a friend of mine, Father Ellwood Kieser. He was a Paulist priest and produced a series called “Insight.” He told me that on occasion he would have one of those episodes: He would lock up the church and make sure no one was around, and he would have it out with God. It was a very cathartic thing for him — he’d get his frustration and anger out. That gave me a platform.

Sometimes you get a part and you don’t quite know how you’re going to play it. I learned as a young actor to project the part on someone you admire. So, I would sometimes pick Marlon Brando, or James Dean or George C. Scott. Then I would pretend I was George C. Scott, and I would play it. Then I would overtake George, and the role would become mine. But having George in my imagination was how I left the starting block and got into the race.

So, I thought of Father Kieser raging in an empty chapel. I had an image of him, but it wasn’t me. It was me being given a responsibility to echo Bartlet, this mighty man who is broken.

But here was an interesting thing that happened. You said your breath was taken away when you watched that scene. The people who ran the cathedral felt exactly the same way, and they were very, very upset. This was very, very ill behavior, and they did not approve. We’d been friendly till then. They were seated in the sanctuary, kind of avoiding my eyes. I tried to explain to them what this was about, but I wasn’t getting anywhere. In frustration, I looked up at the heavens, as if to say, “Lord, how do I explain this?” And, what did I see? I’m right under a stained glass window of Job, raging at God.

It takes a great faith to argue with the Almighty. It takes as much as to do that as it does to worship. On Easter Sunday we get close to the only miracle that had absolutely no witnesses. And it’s the only important one. There would be no faith without the Resurrection. So, we’re called to believe. Thomas wasn’t there, didn’t see it, and when the Master showed up afterward, he refused believe it. That’s kind of where we’re left. It’s very poignant story about what it means to believe. It’s a great, great act of faith and of placing your trust in a mystery.

The people at the cathedral kind of got it eventually. This is like an opera, and you can’t stop the main character from completing their fate. They have to sing their aria. We had a difficult time to get through that sequence, but they finally had some understanding about what the scene was about. It was about Job.

When we have to deal with the real difficult things, we wonder where God is. God dies with us, God is broken with us. The most magnificent, mysterious way that God reached us was through our humanity. God did not come as an angel or a Mighty One. He came as a broken peasant who was vulnerable to all the things we are vulnerable to. His mission was brief, and it would cost him his life. That’s where we meet God: in the mystery of our humanity.

I call that our beautiful, blessed brokenness. You have to experience that in order to be human. And if you’re human, you’re going to experience it whether you like it or not.

So, do you want to ask me what I’d like to be remembered for?

Sure.

Go ahead. Ask me.

So, what would you like to be remembered for?

For about five minutes!

Oh my gosh, why did I take the bait?

You’ve never heard that joke before?

I haven’t, and now I can’t believe that I haven’t.

Because who cares? It’s only those who knew you intimately, who loved you, who worked with you, who shared your life — they’re the only ones you’re going to be remembered by. They knew you.

OK, I’ve taken up enough of your time.

Not at all. You’ve got a list of things to talk about? Go ahead. I’ve been looking forward to this. I’ve told you all my jokes, so you’re safe now.

I only know from instinct that when I did something that I felt was moral, or righteous, or good, and did it humbly, I usually ended up doing it joyfully.

Here’s one. You mentioned grace once in a speech. How do you think about grace nowadays, in your later years? I ask because when I was a kid in Catholic elementary school, grace was pretty straightforward and sensible. But now I find the notion of grace, and sometimes even faith itself, ambiguous and even murky. I feel as if I have to learn how to live while being increasingly aware that there’s so much that I don’t know, even about faith.

That’s what most of the journey is, you know. We don’t know. We don’t know if we’re going to have a room at the end of the day to continue our journey, and yet we keep walking. I don’t think you can separate grace from faith. Could you? I don’t think it’s possible. One depends on the other.

Without faith, it’s very hard to observe grace — is that it?

Yeah. I think that people who have the most grace are the ones who are least aware of it. Like you, the older I get the more I’m engulfed in the mystery, the more I love being alive. The longer I live, the more I embrace the mystery of it: Why? What is this all about? How did this happen? How does this end? What is my mission here? Do I have a mission? Is it important that I have one? I only know from instinct that when I did something that I felt was moral, or righteous, or good, and did it humbly, I usually ended up doing it joyfully. And that usually made me feel grace-filled.

You once told the story of the man who passes away, meets St. Peter at the gates of heaven, and asks to be allowed to enter. St. Peter says, “Sure, show us your scars.” The man says, “I have no scars.” St. Peter replies, “What a pity! Was there nothing worth fighting for?” I also have imagined that scene for years: What will St. Peter say to me when I arrive at the gates of heaven? Is there a question you’re afraid St. Peter might ask you at that moment? I have one, do you?

What’s yours?

St. Peter will say to me, “We gave you so much at the start. Why didn’t you do more with it?”

That’s a good question.

You know what I’m going to say? “Cock-a-doodle-do!” That’s an old Irish joke. An old Irish woman is dying, and a priest is about to give her Last Rites. She says, “Oh, there’s time for that. Let us have a drink.” The priest says, “Oh, for heaven’s sake! You want to go and meet St. Peter with liquor on your breath? What are you going to say to St. Peter?” She answers, “Cock-a-doodle-do!”

The only thing I can wish for when the moment comes — which is really none of my business until it arrives — is I just pray that I will be in the company of a child. I would not want to go alone. I know there are thousands and thousands of children dying all over the world every day, particularly in Africa and from preventable diseases, abandonment, abuse, hunger and starvation. So, I think they’ll be crowding the gate. I want to find myself in that company.