In the late 1950s, a young engineer just a few years out of college decided to build a home for his burgeoning family. Leonard Malin ’55 was embarking upon his adult life at a time of precipitous optimism in a place of boundless expansion. Churning out celluloid dreams and aerospace realities, Los Angeles was in the throes of the incredible demographic, economic and artistic boom of the 20thcentury. From San Pedro to Pasadena, growth enabled the realization of the American dream — a car and a house for every family. And not just any house either, thanks to the populist visions of architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and programs such as the Case Study Houses, through which state-of-the-art model homes were designed for mass consumption. The prosperous Southland middle class could and did own domiciles made of redwood and glass, of concrete and steel, that hovered on the sides of hills, looked out over the growing metropolis, cupped nature in their bosoms, and made good living easy with technological tricks and state-of-the-art appliances.

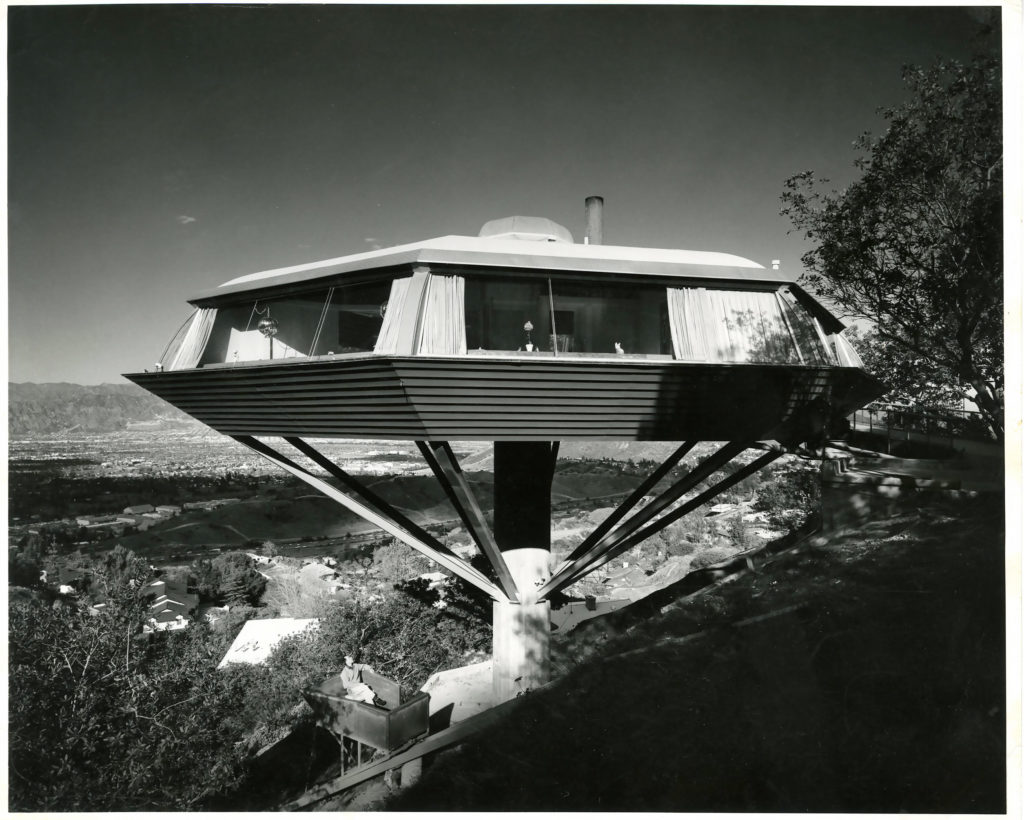

By the dawn of the age of Aquarius, the modestly financed engineer would own one of the most iconic residences not just in California, but in the world: a one-story octagon perched atop a 27-foot pillar that was “everything and more” its builder hoped it would be. The Malin House, aka the Chemosphere, designed by the great 20thcentury architect John Lautner, almost instantly became a symbol of Midcentury Modernism, L.A. and a particularly American rationalist belief in science anchored by pastoral domesticity. So fanciful and futuristic that it has starred in films and inspired TV shows, the space-age building embodies what critic Leo Marx, writing a few years later, would call “the machine in the garden.” The house has been celebrated and abandoned; it has nurtured families, drawn gawkers and even been a site of murder. Almost impossible to see from the street, the Chemosphere is nonetheless an L.A. landmark.

“The Chemosphere was seen as what the future of architecture could be,” says architect Frank Escher, a Lautner expert who restored the building for its current owner. “This was such a powerful statement that you could not ignore it.”

“I never thought that it would be still considered extraordinarily modern 54 years later,” says Malin of the flying saucer on a stick that he called home for 12 exciting years.

Most people don’t live in their dream house until they retire, if then. But Len, as friends call him, is not most people. Born in Ohio on New Year’s Eve 1931, Malin was raised in Los Angeles by his mother. From an early age, he was precocious in both the arts and science. He appeared in several movies singing with Robert Mitchell Boys Choir. You can see him with his hair curled and greased, briskly answering Bing Crosby’s query about a mule, in a vintage clip of “Swinging on a Star” from “Going My Way.” His voice won him a scholarship to Loyola University. He sang with the Glee Club and majored in mechanical engineering, although at that time the program was not accredited. He credits Allen Joyce, Charles Coony, S.J., and L. Clyde Werts, S.J. as the three professors who put Loyola’s engineering and sciences on the map. As of this past fall, he and other 1955 and 1956 graduates still met once a year.

Topology couldn’t stop a dreamer. Malin didn’t want to wait until the last years of his life to live as he imagined.

Malin quickly found employment in the aerospace industry that was pivotal to the Southern California economy. He and then-wife, Diane Bishop, had their first child, Judith ’89, in 1955; three more — Donald ’78, Mary Ann, and Robert — followed. They lived with Diane’s parents in a wooded, hilly part of Hollywood, facing Burbank. The Bishops gave the Malins the lot next door. The only problem: With its steep incline, the property was considered unbuildable.

Topology couldn’t stop a dreamer. Malin didn’t want to wait until the last years of his life to live as he imagined. And in John Lautner he found an architect similarly grounded in mechanical knowledge but blessed with an imagination that seemed to leave the Earth behind.

Lautner learned architecture as a member of Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, which later became the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, in the early 1930s. By 1960 he had garnered international attention with edifices that dispersed with barriers between inside and out, such as his curving Googies coffee shop and the concrete-domed Silvertop residence. For months after the commission, Lautner walked the rugged lot, the glow of his cigarette piercing the twilight.

After much deliberation and some prodding, the architect showed the client four sketches. Malin picked one.

“A couple of weeks later, he called me and said the drawing was ready,” Malin recalls. “He came up with it and unfolded it, and I said, ‘I didn’t pick that.’ And he said, ‘But that’s the one you’re going to build.’ ”

The house looked like something a Disneyland imagineer might have designed. Rather than trying to anchor a structure to the side of a hill, Lautner chose a design that was decades ahead of its time in terms for its minimal footprint: He set the building on a single, central concrete column on a buried concrete pedestal, like a plate on a stick. Steel trusses supported the 2,208-square-feet, four-bedroom structure built around a fireplace. Windows circled the building’s circumference, and the wood ceiling was domed. Lautner told the Los Angeles Times that he was glad the client was an engineer because Malin “wasn’t afraid of an original idea. If he was a banker, he would have insisted on a colonial house on a bulldozed lot.”

Simply figuring out how to build the house was a feat of creative engineering. Malin quit his job to build the Chemosphere; he, site engineer Guy Zebert, and construction manager John de la Vaux figured out how to make Lautner’s vision a reality, on a budget. It was Malin who rigged a pulley system out of telephone poles for hauling up all the supplies. Building was an act of faith and fortitude. “What was it that motivated me?” Malin asks more than a half-century later. “Lack of forethought.”

The biggest hurdle was not logistical, or even getting city planners to green-light their unorthodox plan; it was cost. Malin had $30,000 to spend; Lautner said that would be sufficient, but of course, it was not. The job came in some four times over budget. The engineer convinced several companies, including Chem-Seal Corp., to donate construction materials in exchange for free promotion. That’s why he called the house the Chemosphere, in honor of the state-of-the-art technology for which it became a showcase. For several months after completion, the Malin family couldn’t even live in the structure that had taken all of their money, time and energy, because that the corporate sponsors were showing it off.

Eventually, though, the Malins did make this spaceship tree house their home. The view — through the woods out to the San Fernando Valley — was spectacular. Malin soon supplemented the 113-step staircase entry with a funicular of his own design. The kids would run around on the ledge that circled the building, scaring their mother to death. Or they would perform shows through the windows for the gawkers who came to stare at the house. Living in the Chemosphere was like living in a glass bubble; it brought fame and fake friends, Judith says. Still, it was a magical place to be a child.

“I joke around with my friends that I grew up in a flying saucer and that explains a lot,” says Judith, who, as a relationship coach, is known professionally as Shama Helena. “I loved the fact that nature was right there. We had deer outside, and owls would hang out on the ledge. We had one owl that would come every night, and we would play with him. We had a blue jay that adopted us. … Playing on the hillside was heaven. It was a great place to grow up.”

The house looked like something a Disneyland imagineer might have designed.

Malin and his family lived in the Chemosphere for a dozen years. They sold in 1972 for financial reasons: California’s space program had crashed to earth, and he could not afford the rising taxes in an increasingly wealthy neighborhood as well as college tuition for his children. “He decided that he needed to downgrade so that he could get us into college,” says Judith. “For him, college was extraordinarily important.”

The Chemosphere has become a site of inspiration and intrigue. The TV show “The Jetsons” modeled its space-age domiciles after the Chemosphere; the movies “Body Double”and “Charlie’s Angels” were shot there. As with many Modernist buildings, the structure has tended to be a symbol of decadence, debauchery and danger — as if man had insulted propriety with his feat of ingenuity. In real life, the Chemosphere did house tragedy. Several teens were injured at Judith’s 16thbirthday party when the tram crashed to the ground. The doctor who purchased the home from Malin was murdered in it several years later.

After the house had fallen into disrepair, German art-book publisher Benedikt Taschen bought Malin’s dream house. He renovated the Chemosphere and now uses it for swank parties and as his office. “He’s done a beautiful job with it,” says Malin.

Turned tawdry and then glamorous, the Chemosphere was created as the fantastic setting for a normal life: a high-flying home for a middle-class American family. Its first owner now lives in the desert near Palm Springs. He built a house there, a standard ranch construction that’s only remarkable for the fact that it backs ups to the Yucca Valley Airport. Malin, who piloted his own plane until a year ago, can walk out the back door and onto his friend’s plane, which he does twice a week, flying to meet buddies for breakfast.

Next to his four children, the Chemosphere — the home he built when he was just in his 20s — remains Leonard Malin’s greatest accomplishment. “It was his opportunity to prove what he was made of to himself,” says Judith Malin. “It was his monument.”

Evelyn McDonnell, a frequent contributor to LMU Magazine, is professor of journalism and new media and director of the Journalism Program in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. An expert on music, gender and politics, she has written or coedited seven books, including “Queens of Noise: The Real Story of the Runaways” and “Women Who Rock: Bessie to Beyonce. Girl Groups to Riot Grrrl.” McDonnell is coeditor of the Music Matters series published by the University of Texas Press. She was music editor at the Village Voice and her writing has appeared in Rolling Stone, The New York Times and Billboard. Follow her @EvelynMcDonnell.

This article first appeared in the summer 2015 issue (Vol. 5, No. 2) of LMU Magazine.