In early March 2019, a federal judge in California countermanded the Trump administration’s decision to add a question about citizenship to the national census that will be conducted in 2020. The judge ruled that the federal government’s decision violated administrative law and that it “threatens the very foundation of our democratic system” because it would prevent the government from carrying out its responsibility to count the people living the United States every decade. Judges in Maryland and New York ruled similarly, and the U.S. Supreme Court will arguments on the question April 23 with a ruling expected in June. Here’s a primer about a foundational responsibility of the federal government.

In early March 2019, a federal judge in California countermanded the Trump administration’s decision to add a question about citizenship to the national census that will be conducted in 2020. The judge ruled that the federal government’s decision violated administrative law and that it “threatens the very foundation of our democratic system” because it would prevent the government from carrying out its responsibility to count the people living the United States every decade. Judges in Maryland and New York ruled similarly, and the U.S. Supreme Court will arguments on the question April 23 with a ruling expected in June. Here’s a primer about a foundational responsibility of the federal government.

What is the decennial national census?

The census is the counting of the U.S. population that is undertaken every 10 years by the federal government. It’s the country’s largest peacetime mobilization and arguably its most important.

Who administers the census?

The census is administered by the U.S. Census Bureau, which is part of the U.S. federal statistical infrastructure and housed within the U.S. Department of Commerce. Most personnel working on the census are nonpartisan career federal employees. At a broad level, the agency’s direction is set by Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross.

Does the census have a basis in the U.S. Constitution?

Indeed, it does — it’s actually the very first affirmative responsibility given to the federal government, six sentences in. The U.S. government is required to conduct a counting of the U.S. population — an “actual Enumeration” — in accordance with Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution, and later, the 14th Amendment.

Why is the census important?

The census is the foundation of the nation’s representative democracy. The counting of the population determines the allocation of representation for federal, state and local government. Seats in the House of Representatives are reapportioned, and election districts are divvied up, based on changes in where the population lives. After each census, some states will gain House seats and others will lose seats, and representation within each state, at all levels of government, will shift. The census is also the basis for allocating hundreds of billions of dollars in federal and state spending, and the basis for our basic information architecture. Whenever you read a poll or a survey that says it’s based on a “representative sample,” we know the sample is representative based on the census and other assessments connected to the census. It’s at the root of much of the public policy and private business decisions we make.

“The census is the foundation of the nation’s representative democracy. ... It’s at the root of much of the public policy and private business decisions we make.”

Why has the questionnaire for the 2020 census become particularly controversial?

On March 26, 2018, Secretary Ross decided that the census would include a question, asked of every household in the country, inquiring about the citizenship status of all respondents. Critics of that decision say that adding that question in the current charged political environment will lead some people to not fill out the census, creating a flaw in the census that will undermine the most crucial goal of the process: to accurately count the U.S. population. The last time such a question was asked of every household in the country was in 1950. It was omitted in the 1960 census. Starting in 1970, a citizenship question was asked in other, much lengthier government surveys that were distributed to smaller portions of the U.S. population. A question about citizenship is still asked in the context of that longer rolling survey today, and it has been causing census takers some concern of late. Advocates worry that elevating the prominence of the question will elevate the concern.

In what ways could the presence of the citizenship question impact the accuracy of the enumeration?

Critics believe that in this atmosphere, people will refuse to answer the census questionnaire, degrading the accuracy of the enumeration and jeopardizing the Census Bureau’s one constitutional mandate. They also believe the quality of the data will deteriorate due to people fabricating answers in order to not reveal information that they fear could harm them or their family members. Some estimates suggest that perhaps a third of noncitizens who respond to the census may falsely present themselves as citizens in their responses. In 1980, the Census Bureau itself argued in federal court against including a citizenship question because doing so would impair the accuracy of the enumeration required by the Constitution, and several former directors of the Census Bureau, from both Republican and Democratic administrations, have argued against adding the question now.

Does the Census Bureau typically take steps ahead of time to determine if adding new or additional questions to the questionnaire may impact the response rate?

Yes. The bureau usually rigorously tests proposed changes in the census in the years between enumerations for exactly that reason. Some aspects of the upcoming 2020 census were tested as early as 2007. Early in 2018, the Census Bureau conducted its final “End-to-End Census Test,” commonly called the “dress rehearsal.”

Was the citizenship question tested?

Not in this context. It’s been tested in the longer survey sent to a small portion of the population. But it hasn’t been tested in the context of the 11 questions sent to every household in the country. The citizenship question was added after the dress rehearsal, which was too late for adequate testing in an environment that approximates the actual decennial enumeration.

What are the possible consequences of a faulty enumeration?

First, the enumeration drives the apportionment of congressional districts as well as redistricting at state and local levels. Therefore, it could lead to unfair apportionments of political representation at multiple levels of government. Second, the results of the census impact the distribution of billions of dollars in the form of government grants and expenditures in states and communities around the country. States with a rapidly growing population — such as Texas, Florida, California, Arizona, North Carolina and Georgia — may particularly suffer. Third, the census drives our information infrastructure: It’s how we get a picture of America, and an error in the process will lead to errors in the picture that infect public and private decision making. Last, if the citizenship question decreases the accurate response rate, it may constitute a constitutional dereliction of duty.

"If the citizenship question decreases the accurate response rate, it may constitute a constitutional dereliction of duty."

What is Secretary Ross’ justification for adding the citizenship question to the census?

Ross has argued that the Department of Justice requested the question be added to the census in order to better enforce the Voting Rights Act.

Are there reasons to doubt that account?

Yes. For its entire history, the Voting Rights Act has been enforced without asking every household in the country about citizenship. I helped to run the wing of the federal government devoted to enforcing the Voting Rights Act, and neither I nor any of my predecessors, in any administration, sought citizenship information. Nobody has identified even a single case in the past two decades that failed but would have succeeded if only citizenship information had been collected in this way. And the private civil rights organizations with a vested interest in enforcing the Voting Rights Act and its provisions uniformly oppose adding the citizenship question to the census in this climate. Last, evidence suggests that months before the Justice Department actually made the request for the citizenship question, Secretary Ross discussed with Commerce Department staff ways to persuade the Justice Department to make that very request. The Justice Department eventually made the request, but it appears to have been at Secretary Ross’ urging, as a pretext for a decision that had already been prebaked.

Are there reasons why the current administration would want a census with less accuracy, particularly if noncitizens would be undercounted?

An inaccurate result driving down the total count might — falsely — indicate success in a federal policy that discourages immigration. It could allow certain states to unfairly — and, again, inaccurately — maintain or increase federal representation, and would likely create similar distortions in state and local representation. Last, there may be a coming legal fight over apportioning representation to only some subset of residents, including some and excluding others in a way starkly contrary to our shared historical practice. Some officials may seek to use a census count of citizens to redraw district lines and reapportion representation on a differing basis that benefits their political interests. And it could legitimize the notion of assigning representation based on a system far more open to political manipulation.

What can concerned individuals do?

There are several pending legal challenges to placing the question on the decennial census: Courts in New York and California have already said the Commerce Department’s process was illegal. One such challenge will be heard in the Supreme Court this spring. But whatever the result of the case, it’s going to be extremely important that every person in the United States stand up and be counted when the census comes around. The reasons for concern only manifest if people are too scared to respond to the census — and though the fear is real, there are also real protections, both practical and legal. Local communities, particularly throughout California, will be mobilizing “Get Out the Count” efforts to make sure that everyone in the country has a voice, and everyone can help by supporting these efforts to make sure that the count is fair and accurate.

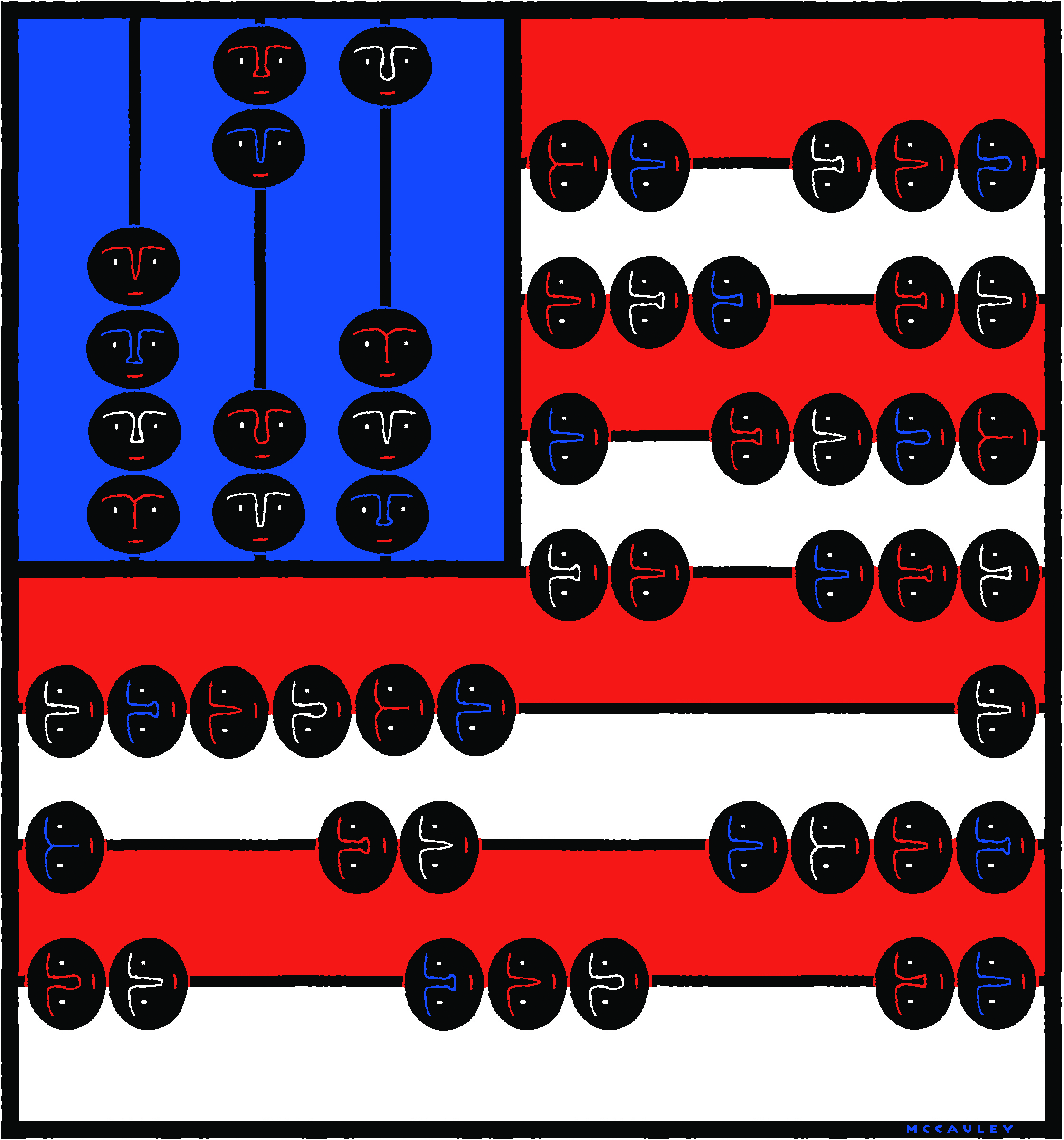

Photo by Jon Rou

This article appeared in the spring 2019 issue (Vol. 9, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.