Jackie Robinson, a native of Pasadena, Calif., transformed major league baseball when he took over second base for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. He also changed U.S. society, by becoming the living symbol of desegregation and, in time, a tireless advocate for civil rights for African Americans. Robinson’s life was the subject of a major Hollywood film this spring — “42” — that was written and directed by Brian Helgeland. Helgeland was interviewed just before the film’s release by Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch.

You’re known for your period films — “L.A. Confidential,” “Robin Hood,” “A Knight’s Tale.” How did you approach “42,” which takes place in 1946–47?

I wanted to deal with the period and then get it out of the way. The danger in period movies is they immediately lose their relevance for a modern audience. You want to honor the period but not allow it to distance the audience from the people they’re watching. I always approach period films from the point of view that people don’t change. The times change, technology changes, and world events come and go as far as their impact, but people don’t change; human emotion doesn’t change.

Robinson had a remarkable life after baseball. Why did you focus on 1946–47?

My theory is that, in general, the passage of time is the enemy of a film. If you could tell a film in real time, that would be ideal. The longer it takes for a story to unfold, the harder it is to maintain the momentum and the drama. In a cradle-to-grave story, you’re always stopping and starting, even using different actors for the same role in some cases. With Robinson, I wanted to pick a crucible moment, illustrate the man through a moment in his life, and jettison everything before and after.

When you wrote “42,” you weren’t in control of your main character: Robinson made decisions that you have to be faithful to. Was that a challenge?

Any writer brings his own strengths, weaknesses and interests to whatever he does. That can serve you really well. I’m interested in identity: how a person sees himself and how a person is true to himself, or not. In my film “Conspiracy Theory,” the main character can’t remember who he is and is trying to remember. In “A Knight’s Tale,” the character is trying to be the person that the world won’t let him be. In “42,” it’s a story about: a) Jackie’s identity and b) the country’s identity. It raises all those questions about what is America, what does America want to be, what is America trying to be, and what is it really? So it seemed like an identity story, which fit in with what I know I’m good at doing.

But in “42” Robinson doesn’t discover his identity during the course of the film, does he?

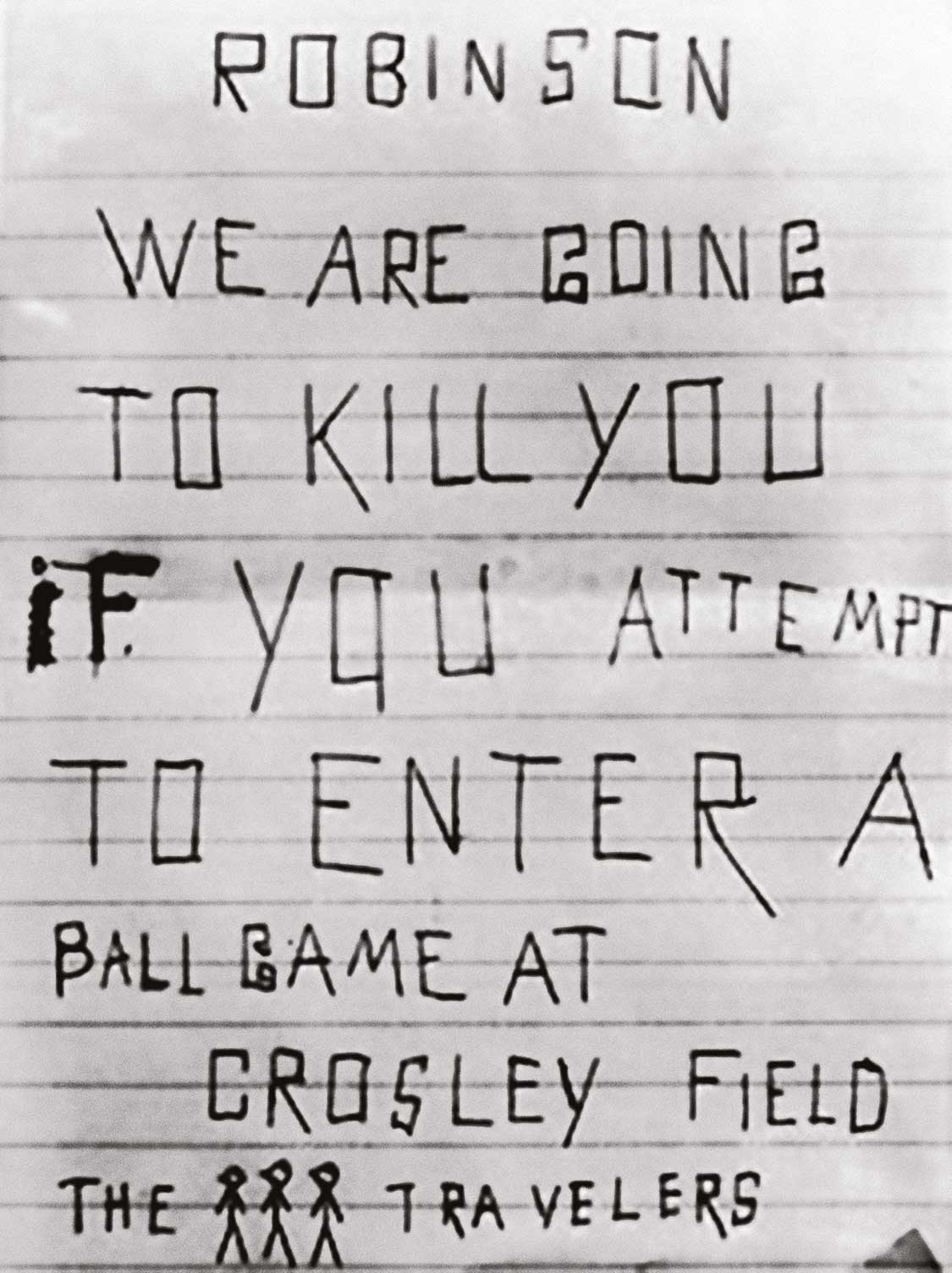

Right. In the movie, he doesn’t change. There’s a silly Hollywood rule that says your main character has to undergo some transformation, which I don’t think is true. Robinson is the catalyst. He comes in and goes out the same guy. Someone once said that Robinson is changing the world but refusing to let it change him. He forces a lot of the guys on the team to look at themselves, with Pee Wee Reese being a great example. There is a famous moment when Pee Wee puts his arm around Robinson on the field. I was careful not to make it condescending, as if he were saying, “I, as a white man, have accepted you.” He does it to show everyone in the crowd who Pee Wee is. That moment is about Pee Wee declaring himself to Cincinnati, where the game was played, and to his family from Kentucky who came to the game. In the movie, he says: “I have family up there. I need to let them know who I am.” That’s the power of Jackie Robinson: He forces all these people to confront who they are and either change or dig in further. Fact or fiction, you don’t get to do a story like that very often.

Robinson was in the army during World War II. he didn’t see combat, but did the war shape his awareness of racism?

Robinson came along in the aftermath of World War II. In that war, African American soldiers fought and defeated a regime based on racial superiority, and returned to Jim Crow laws and discrimination. Segregation was untenable. They didn’t want to return to a watered-down version of what they defeated. For Robinson, awareness starts with Jesse Owens and the 1936 Olympics. His brother, Matthew, was second in the 200m race after Owens. But afterward, he came home and collected trash in his Olympic track suit because it was the only job he could get. Jackie would’ve seen his brother like that every day.

Why do you care about Jackie Robinson?

Because of his courage and bravery on a day-to-day basis that he showed for years. I was fascinated by that. As a writer, I was looking for his dark, despairing moment in that season and could never find it. I went to see Ralph Branca, the only player, I believe, from that team who is still alive. I asked him about it, and he simply shook his head. He looked at me like I was an idiot, and he just pointed to his stomach. I said, “I’m sorry, Mr. Branca, I don’t speak finger.” And he said, “Guts. Guts. Jackie was the bravest man I ever saw. I wouldn’t even say who No. 2 was, because it would be an insult to him.” I got the feeling that Robinson didn’t have a lot of friends from team members but he had a huge amount of respect on the team because everyone could see the moral courage. Where does that come from? Someone sent me a black baseball with “Thank you, Jackie” written on it. I thought the movie should be a thank-you to him and show his courage. I wanted to show his struggle and celebrate that. His number is retired today because of what happened in 1946 and 1947, so that’s the focus of the film.

Are there ways in the filmmaking that you tried to make Robinson contemporary?

One thing you notice about Jackie Robinson in photos is he always looks more contemporary than the people around him. We didn’t want to lose that feeling. Contemporizing things like costume design — how the characters look — helps draw the issue itself into the modern world. In my film “L.A. Confidential,” none of the three main characters wore a hat. It seems silly, but that was very important as far as contemporizing those characters for the audience. In “42,” Jackie doesn’t wear a hat off the field. Not having the hat makes him look a little more modern. In a subtle way, it served the larger notion that racism didn’t cease to exist when Robinson walked onto Ebbets Field. There’s a school of thought that says, “Thank goodness that stuff is all behind us now,” which is not my point of view.

You've written and directed films. How would you describe the difference between the writer’s responsibility and the director’s?

We talk about directors as if they are auteurs, like Picasso, when really filmmaking is a collaborative art. It isn’t for the writer. After the writer is done, the project is turned over to others, and it becomes a collaborative process. The writer can either get on board for it or reject it and isolate himself from it. If you’re directing, you have to protect the film but in a generous kind of way. You have to know what a movie can bear and not bear, and pick your fights. The actors, if they’re serious and intelligent, are going to know their characters better than you do. They focus only on that for months. And the production designer is going to know what works better than you. So it’s hubris to think that you’re the creator of it all. There’s a creative party going on, and you’re the host. You get to invite people to the party, and you get to take the car keys away and throw people out of the party, but you’re not the party.

Which do you like more, writing or directing?

I find writing satisfying in a deep way, but I don’t find it enjoyable. As soon as I start, I think about when I’m going to be done and how to get to the finish line. So I find writing onerous, and directing is kind of a joy. It’s like building a beautiful structure, but you have to get the foundation laid and deal with the plumbing. As a director, you’re a contractor. It’s the greatest blue-collar job that exists on earth. But you can’t have one without the other. You pay for it when you’re writing, and you get the benefit of it when you’re directing.

What’s the scene from your film “42” that never leaves you?

There is a story line in the movie where a little African American kid in 1946 follows Robinson around during spring training and, finally, to a train station. Robinson has made it on the Dodgers’ Montreal minor league team in 1946, and he’s on his way by train to the first game up north. The train leaves, and the kid chases it until it’s gone. Then, he puts his ear down on the tracks. He pops up, looks at his friend and says, “I can still hear him.” To me, that became the reason why the movie should get made. I can still hear Jackie Robinson. If you look at the country and the world, you can still hear him. That’s an amazing thing. Millions of people have passed through the world since 1947, but here’s a guy whose life continues to echo.

Brian Helgeland is a writer and director of major films. His screenplay, “L.A. Confidential,” which was adapted from James Ellroy’s noir novel, won an Academy Award in 1998. “Mystic River” was nominated for an Academy Award in 2004. His other films include “A Knight’s Tale,” “Robin Hood” and “Conspiracy Theory.” Helgeland was born in Providence, R.I., and he earned a master’s degree in film studies from Loyola Marymount University in 1987.