In January 1963, the same month that saw the publication of James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time” and its stark, prophetic warning about America’s “racial nightmare,” a new governor of Alabama was inaugurated. George Wallace thundered on the occasion: “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!”

Over the course of the spring, Birmingham, Alabama, would become the latest stage for the Civil Rights Movement, providing images that inspired — and — shocked the world. Lunch counter sit-ins. Hundreds of young children marching. Fire hoses and police dogs turned on peaceful protestors. Martin Luther King Jr.’s mug shot and prison cell. Arson and dynamite attacks of the sort that earned the city a gruesome nickname: Bombingham.

On July 11, President John F. Kennedy addressed the nation. “A great change is at hand, and our task, our obligation, is to make that revolution, that change, peaceful and constructive for all. Those who do nothing are inviting shame, as well as violence. Those who act boldly are recognizing right, as well as reality. Next week I shall ask the Congress of the United States to act, to make a commitment it has not fully made in this century to the proposition that race has no place in American life or law.”

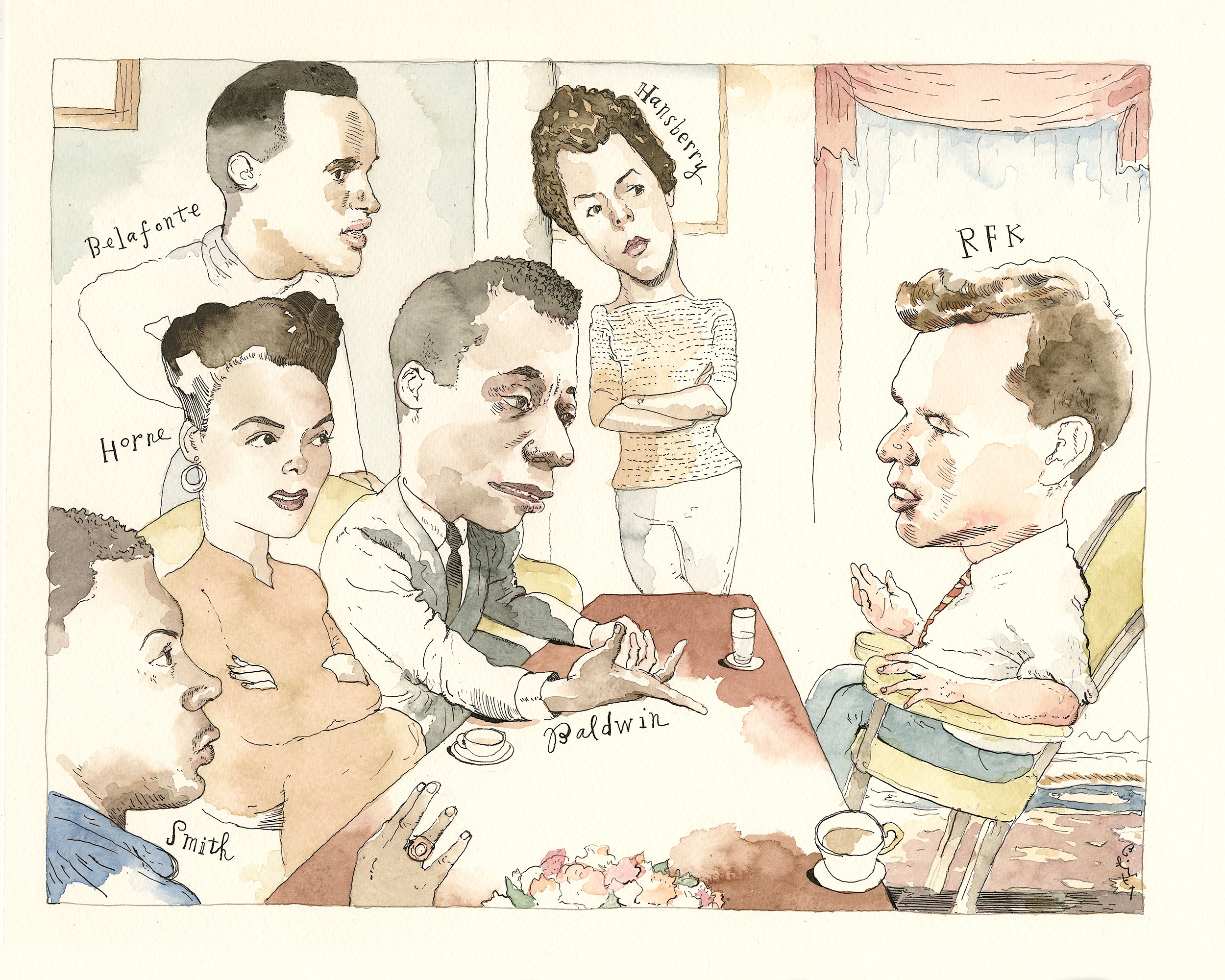

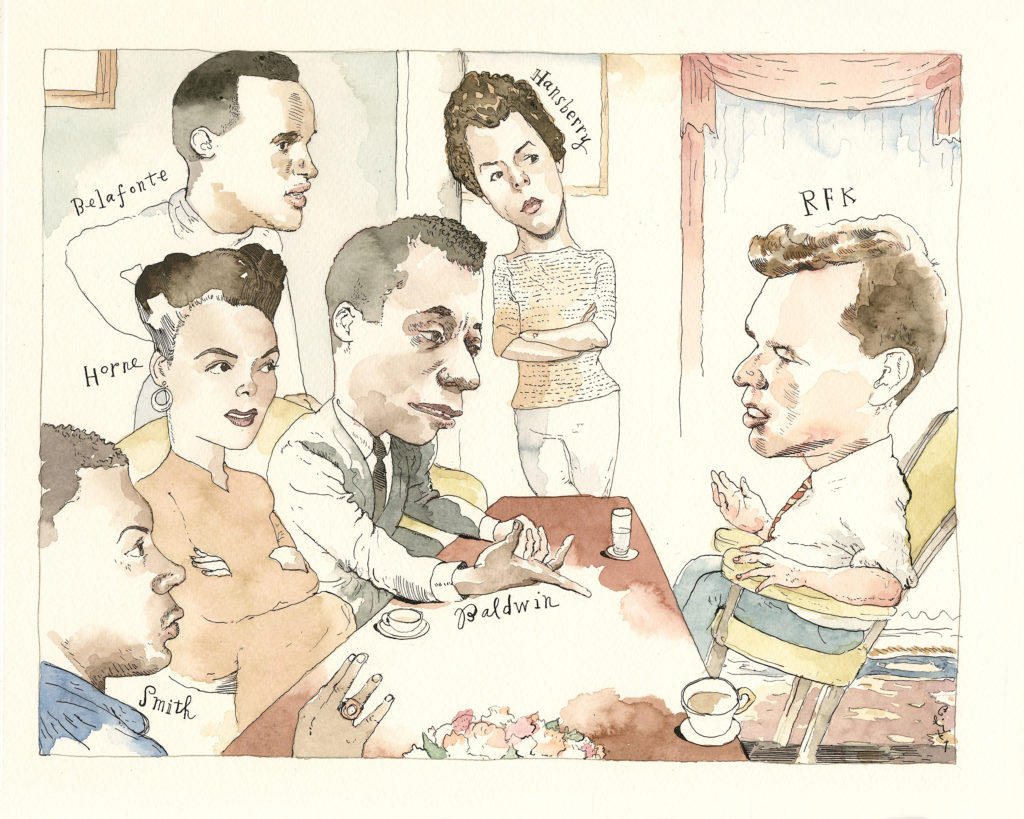

But there was another stage for the action, far from Alabama, that few knew about in the spring of 1963. No transcripts or photographs or newsreels were recorded. Its attendees, including Baldwin, agreed to keep it a secret, but almost as soon as they left the scene — a palatial apartment building overlooking Central Park in New York City — competing stories of what happened, and what it meant, sprang up like crabgrass.

RFK’s guests had not come for a lecture on the virtues of patience. All their lives they had been told to be patient — to “go slow.”

It was the president’s brother — Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy — who invited Baldwin to talk. When they spoke on May 23, RFK said he wanted to get together with Black thinkers and public figures who could command the respect of Blacks throughout the country. Even after the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955–56, the Little Rock high school crisis of 1957, the student sit-in movement of 1960, the Freedom Rides of 1961, and the Birmingham campaign that began not long after Wallace took office in 1963, the Kennedys did not know where to start in contacting Black leaders who could help them understand the thinking of Black Americans. So, RFK started with Baldwin, perhaps the most famous writer of his time — he was on the cover of that week’s Time magazine — and a vocal critic of the Kennedys’ seemingly glacial pace in matters of race.

“Can you find some people who can tell me what the government can do?” RFK asked. “Yes,” Baldwin replied, “I know just the people.” They arranged to meet the next evening at the Kennedys’ apartment at 24 Central Park South. “So, I said okay, not quite realizing what I’d gotten myself into,” Baldwin later recalled. “I called up a few friends. The bunch of people I knew are fairly rowdy, independent, tough-minded men and women.”

The May 24 meeting, then, came together in much the same way one of Baldwin’s stage plays, like “The Amen Corner” (1954) or the civil rights play he was working on, “Blues for Mister Charlie” (1964), might come together.

On extremely short notice, Baldwin assembled the cast. It included Lorraine Hansberry, whose “A Raisin in the Sun” (1959) had been the first play written by a Black woman to be staged on Broadway. It included movie stars Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne, who had been active in the movement for years. It included the Black psychologist and Harlem community organizer Kenneth Clark. It included two men with deep knowledge of policy and political institutions: attorney Clarence Jones, one of King’s most trusted advisors, and Edwin Berry, executive director of the Chicago Urban League. It included Baldwin’s brother, David, and several other personal friends. Finally, and most consequentially, it included a 25-year-old civil-rights activist named Jerome Smith, who had been brutally beaten by white mobs more than a dozen times as a Freedom Rider in the early ’60s. A native of New Orleans whom Baldwin had met amid their Deep South movement work, Smith was in New York to receive medical care for his injuries — he would suffer from headaches and damaged eyesight for the rest of his life.

With Burke Marshall, head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division, alongside him, RFK welcomed the visitors. Sure enough, and to his surprise, they were rowdy, independent and tough-minded.

“There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation,” Baldwin responded to a William Faulkner statement. “The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”

RFK began the meeting by enumerating the accomplishments of the Kennedy administration in civil rights. His visitors knew all this. “We all wanted more,” Horne recalled, “but he didn’t realize how much we expected of him and how much more we felt had to be done, and quickly.” Their dissatisfaction was palpable.

RFK shifted from boasting about progress to counseling patience. “We have a party in revolt,” he said, “and we have to be somewhat considerate about how to keep them onboard if the Democratic Party is going to prevail in the next elections.”

This didn’t work either. RFK’s guests had not come for a lecture on the virtues of patience. All their lives they had been told to be patient — to “go slow,” as the Mississippi novelist William Faulkner had advocated in a notorious 1956 public statement that raised Baldwin’s ire to such a degree that he soon decided to return from France, where he had lived since 1948, to take a greater role in the movement. “There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation,” Baldwin had responded to Faulkner. “The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”

As it became clear that RFK was failing to sway his audience, his exasperation mounted. When he began to complain that Black people, rather than appreciating the Kennedys’ progressive actions, were flirting with extremists like Malcolm X and bringing the country closer to chaos, Smith, a longtime follower of the nonviolent teachings of Gandhi and King, could hold his silence no longer.

“You don’t have no idea what trouble is,” he burst out at the attorney general. “Because I’m close to the moment where I’m ready to take up a gun. I’ve seen what government can do to crush the spirit and lives of people in the South.”

RFK was scandalized. Smith outraged him further when he said he would never consider fighting for the U.S. in a foreign war. “How can you say that?” demanded the attorney general, who had lost one brother, and nearly two (JFK had survived a serious injury in the Pacific theater in 1943), during World War II.

RFK’s turn to speak was over. He slumped in a chair, listening, watching and seething. His guests berated him for the administration’s failure to protect Black lives. They railed on the FBI, which had long spied on leaders like King and sought to disrupt even the most nonviolent and peaceful civil rights organizing. They scoffed at his praise for Justice Department agents, some of whom, Smith said, had stood watching while he and his friends were beaten by racist whites. They came at RFK for nearly three hours, in wave after wave of frustration and rage, exhorting the attorney general to recognize the moral rather than political stakes of the racial crisis in America. Hansberry reminded everyone of a recent Time photograph, an image of a Birmingham policeman kneeling on a Black woman’s neck. Questioning the moral condition of a civilization that could produce such “specimens of white manhood,” she was the first to leave.

“It was all emotion, hysteria,” RFK said privately afterwards, still in disbelief at what he had seen and heard. “They stood up and orated — they cursed — some of them wept and left the room.”

Some of his guests were inclined to agree. “It really was one of the most violent, emotional verbal assaults and attacks that I had ever witnessed,” Clark later commented.

Lorraine Hansberry reminded everyone of a recent Time photograph, an image of a Birmingham policeman kneeling on a Black woman’s neck.

Lena Horne credited the brutal honesty of Smith with transforming the meeting from a polite discussion of federal policy into something more elemental. “He communicated the plain, basic suffering of being a Negro,” she wrote in her autobiography. “The primeval memory of everyone in that room went to work after that. We all went back to nitty-gritty with that kid who was out there in a cotton patch trying to get poor, miserable Negro people to sign their names to a piece of paper saying they’d vote. We were back at a level where a man just wants to be a man, living and breathing, where unless he has that right, all the rest is only talk.”

Some of those present told a New York Times reporter, anonymously, that the meeting had been a “flop.” Baldwin continued to criticize the Kennedy administration’s approach to race as “totally inadequate,” but he refused to characterize the meeting as a failure. It was, he said, “significant and, I hope, beneficial.” Time, he believed, would tell.

In subsequent days, RFK seemed traumatized not just by what he felt was an unfair judgment against him but more fundamentally by such an unchecked outpouring of feeling. The experience gnawed at him, and slowly he began to view the meeting differently. “After Baldwin, Bobby was absolutely shocked,” said Nicholas Katzenbach, one of RFK’s deputies. “But the fact that he thought he knew so much — and learned he didn’t — was important.” A few days later, he had come around to view Smith in a different light. “I guess if I were in his shoes,” Kennedy admitted to his press secretary, “if I had gone through what he’s gone through, I might feel differently about this country.”

Soon RFK’s lifelong concern for victims and underdogs, an engagement deepened by his Catholic faith, was manifesting itself more prominently in what biographer Evan Thomas described as a “leap from contempt to identification” and a “transformation from rage to outrage.” He pushed federal agencies to hire more Blacks and scolded Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson — whose own transformation would enable him to make enormous contributions to the cause of civil rights in the coming years — for the government’s inaction in much the same terms he had been scolded by Baldwin’s cast. And he turned up the pressure on his older brother. It was time, he insisted, for the president to declare civil rights a moral imperative, and to advocate new laws that would get to “the heart of the matter” and destroy Jim Crow.

President Kennedy knew that the politics of civil rights were far from straightforward. The Democratic Party still enjoyed strong support from much of the white South and counted a number of prominent segregationists among its Congressional ranks. Maintaining this devil’s bargain had become, in recent years, an art form, one which the Kennedys themselves had practiced with great skill and calculation. Unequivocal support for civil rights of the sort RFK now demanded would transform the party, encouraging segregationists to look for a new home where their institutional racism was more welcome. Many of the president’s advisors regarded RFK as a hothead, undisciplined and politically naïve, whose agitation for civil rights legislation could splinter the party. They may well have been correct. But the president overruled them, siding with his brother.

On June 11, soon after the National Guard assisted several Black students in the integration of the University of Alabama while Governor Wallace staged a futile protest for television cameras and raged against the “military dictatorship” of the federal government, JFK also appeared on television.

“We are confronted,” he said, “primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the Scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution.”

Baldwin, then in Puerto Rico in search of solitude to work on his play, might have reveled in this choice of the words, which he had been articulating for a long time. But he was not the sort to celebrate such things, and, anyway, he soon learned that his good friend Medgar Evers, a World War II veteran working as field secretary of the Mississippi National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, had been shot down in his own driveway by a white supremacist just a few hours after the president’s speech. Baldwin would dedicate “Blues for Mister Charlie” to Evers. The struggle would continue. It continues still.

If RFK had looked inside the issue of Life magazine that arrived on May 24, the date of his secret meeting in New York, he would have found yet more coverage of the celebrated Baldwin: a photo essay documenting Baldwin’s recent trip through the South, during which he had given a few lectures and spent time with Evers and other activists. RFK could have read Baldwin’s words in the Life interview and perhaps learned something of the demands Baldwin made on his audience: “Most contemporary fiction, like most contemporary theater, is designed to corroborate your fantasies and make you walk out whistling. I don’t want you to whistle at my stuff, baby. I want you to be sitting on the edge of your chair waiting for the nurses to carry you out.”

It was not quite that extreme. RFK had, at least, exited the meeting under his own power. But he had experienced something remarkable and had been changed, in ways that also would change his country, during that James Baldwin Production staged in his living room.

Robert Jackson is a professor of English at the University of Tulsa in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He is the author of “Fade In, Crossroads: A History of the Southern Cinema.” His “Hollywood Caste” appeared in the winter 2017 issue (Vol. 8, No. 1) of LMU Magazine.