Online higher education has historically been viewed with cynicism by the brick-and-mortar university establishment — arguably with good reason. Several national online programs have posted appalling graduation rates and left students saddled in debt with nothing to show for it. In the past few years, the phenomenon of MOOCs — short for “massive open online courses” — has emerged as, in the opinion of some, a game-changer. One Stanford course, for instance, drew 104,000 enrolled students. This past March, Coursera, a for-profit education technology company, scored a major coup by landing Rick Levin, former Yale University president, as the company’s new CEO.

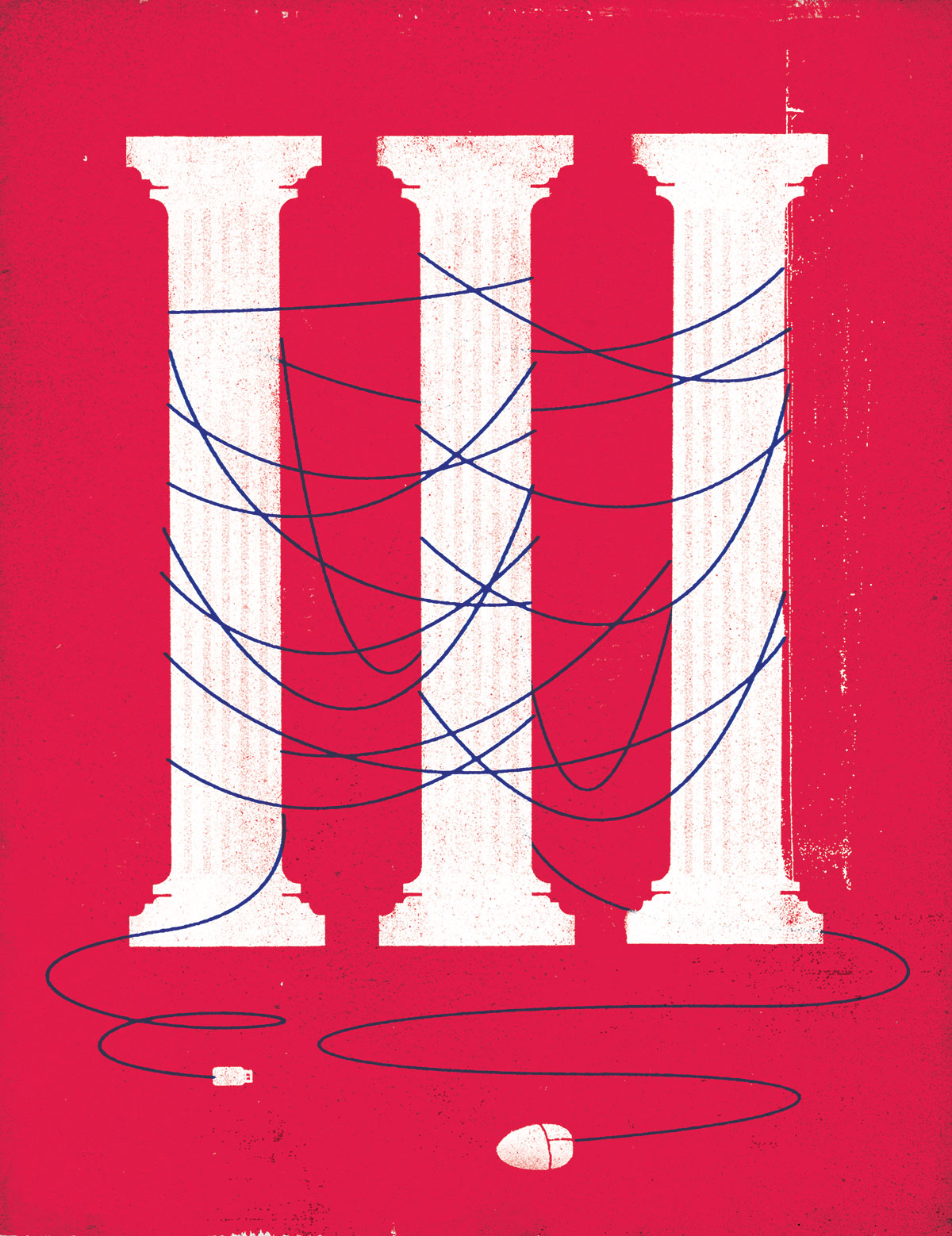

High-profile hires like Levin’s may indicate that educational progress lies in MOOCs or that for-profit companies are an education growth engine. But whether or not massive online classes represent the future of U.S. higher education, the continuing revolution in online technology is leading universities across the nation to examine if they can adapt emerging technology to their curriculum and, for some, if they should.

LMU is no exception. In February 2013, the university created a Technology-Enhanced Learning Subcommittee to study LMU’s online offerings and set future direction. The potential benefits of developing a robust online education program for a university are significant: advancing the institution’s brand, or reputation; increasing revenue, a concern for all universities; and improving its ability to fulfill its educational mission.

Sorting out the benefits was a major focus of the task force, says Lynne Scarboro, senior vice president for Administration and the task force chair.

“Every institution has to make a decision about those very points, because you can’t have it all,” Scarboro says. “For instance, tuition income is usually the greatest source of revenue. If you want to increase revenue, you have to increase students. But that increases the student-to-faculty ratio, potentially impacting the quality of the education you’re offering. One of the main questions the task force looked at was ‘Does going farther with online education offerings represent a change in who we are, or are we going to be true to our mission?’ ”

At LMU, MOOCs — realistically speaking — are out of the question. “The universities experimenting with MOOCs tend to be large, public institutions or those with extensive resources,” says Executive Vice President and Provost Joseph Hellige. Also, the compatibility of MOOCs with LMU’s commitment to educating the whole person and promoting students’ access to faculty would be debatable.

Instead, the issues LMU has debated are whether to offer undergraduate and graduate degrees, programs or courses online and how to employ online tools consistent with the university’s personal approach. Some conclusions have been reached, says Scarboro, including: Loyola Marymount University will not offer entire undergraduate degrees online, though sections of some undergraduate courses may be available online; will offer some strategically chosen post-baccalaureate programs fully online; will establish approval processes to ensure the quality of online and “hybrid” courses and programs; will ensure that faculty play a critical role in crafting online initiatives; and will encourage faculty development workshops and programs to support online and “blended” learning offerings in graduate and undergraduate settings.

This isn’t to say LMU has steered clear of the online world until now. First, the university has already built up its technical capabilities in online education.

“Over the past five to 10 years,” says Patrick Frontiera, vice president for Information Technology Services, “we have developed and put in place all the pieces and infrastructure to enable academic strategies that will further students’ education at LMU: a strong network that facilitates data transmission, a learning-management system and a web-conferencing system that allows people to synchronously participate in courses from a distance.”

Second, the past several years have been marked by an uptick in online and technological experimentation in the classroom. Professors have been increasingly encouraged to develop hybrid courses, in which classes are held online during the week and face to face on weekends, or use flipped classrooms, where lectures are posted online and classroom time is reserved for group discussion.

"SOMETIMES IT’S GOOD TO INCONVENIENCE STUDENTS, BARRING FAMILY CONCERNS. I THINK WE’RE AT AN INTERESTING MOMENT, WHERE WE’RE THINKING TOO MUCH ABOUT GIVING STUDENTS WHAT THEY WANT, INSTEAD OF US TELLING THEM WHAT THEY NEED."

EARLY EXPERIMENTS

Some efforts have been well received. For example, Tom Plate, Distinguished Scholar of Asian and Pacific Studies, teaches a seminar on Asian politics and media that uses online technology to bring together in real time — through audio and visual linking — LMU students in a University Hall classroom and students in a room at United Arab Emirates University in Al Ain, UAE.

But the School of Education has made the most use of online education. SOE offers LMU’s only fully online degree in graduate-level reading instruction. Ernesto Colín, chair of SOE’s instructional technology committee and assistant professor of specialized programs in urban education, has adopted technology in his graduate classes. Colín employs a hybrid class format — using online technologies like online discussion boards, online archives of lectures and Skype as a way to meet with students.

“I’m typically dealing with professionals who often have families and who can’t carve out every Monday at 4 p.m. to come to class,” Colín says. “Teaching hybrid is the best of both worlds.”

While LMU is turning its attention to the question of how to best adapt to changing educational technology, some faculty and staff fear that core educational principles could be sacrificed in an effort to keep up with the times.

“Technology itself is a tool, just like textbooks were after the invention of the printing press,” says Amir Hussain, professor of theological studies in the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. “But it seems like we get so caught up in the tech side of things that I wonder if it’s just a distraction. I know it sounds horrible to say this, but sometimes it’s good to inconvenience students, barring family concerns. I think we’re at an interesting moment, where we’re thinking too much about giving students what they want, instead of us telling them what they need.”

SMART TECH

Margaret Kasimatis, associate provost for Strategic Planning and Educational Effectiveness and a member of the technology task force, says she shares those concerns. “We don’t want to use tech just to use tech,” she says. “We need to strategically select which programs we put online. Technology has to enhance learning. We’re not diving in willy-nilly. We’re going to be smart.”

In the evolving and amorphous world of online education, however, being smart is easier said than done. Do you teach the class synchronously, classroom-style, or asynchronously, letting students access the material on their own time? What technology should be used? What should a course website look like?

Erica Tartt, senior instructional designer charged with helping create best practices in adapting classes to an online or hybrid format, says LMU’s approach is far more measured than most institutions, which see online technology as a way to rapidly expand enrollment. In keeping with its philosophy of cura personalis — care for the entire person — LMU plans to keep its focus on replicating its tradition of small, intimate classroom settings in an online format.

“We want our online presence as strong as it would be in a physical classroom,” Tartt says. “If a classroom can hold 50, we’re going to limit the online class to 25. That’s not alarming, it’s refreshing.”

Yet even the university’s measured approach has its skeptics.

“The heart of LMU is a liberal arts education in the Jesuit model,” argues Brian Treanor, professor of philosophy in the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. “I can’t conceive — and I have a vivid imagination — how that could be exported into an online format. A lot of what happens in a Jesuit education simply can’t be delivered over Skype. It’s too episodic. You can’t convey nuance. People miss sarcasm or irony.

“If there were a global pandemic of H5N1 bird flu, I’m sure I could manage a class online. But it wouldn’t be the same.”

Both Treanor and Hussain see the potential benefit in embracing technology-based learning for the university’s professional schools — where technology isn’t just a means of teaching, it’s often the subject. Both, too, would like to see LMU’s humanities footprint expanded — although not at the expense of its defining ethos.

But Shane Martin, dean of the School of Education and Graduate Studies, believes using educational technology doesn’t put the institution’s ethos at risk.

“There’s nothing inconsistent about LMU adopting the best technology and approaches of online education,” says Martin. “Ignatius himself was a practical leader who encouraged the Jesuits in their worldwide missions to find effective, appropriate solutions to local problems. It’s very Ignatian to see new educational technologies as tools that, when used in ways consistent with our mission, can help us educate the whole person, just as we've been doing for decades.”