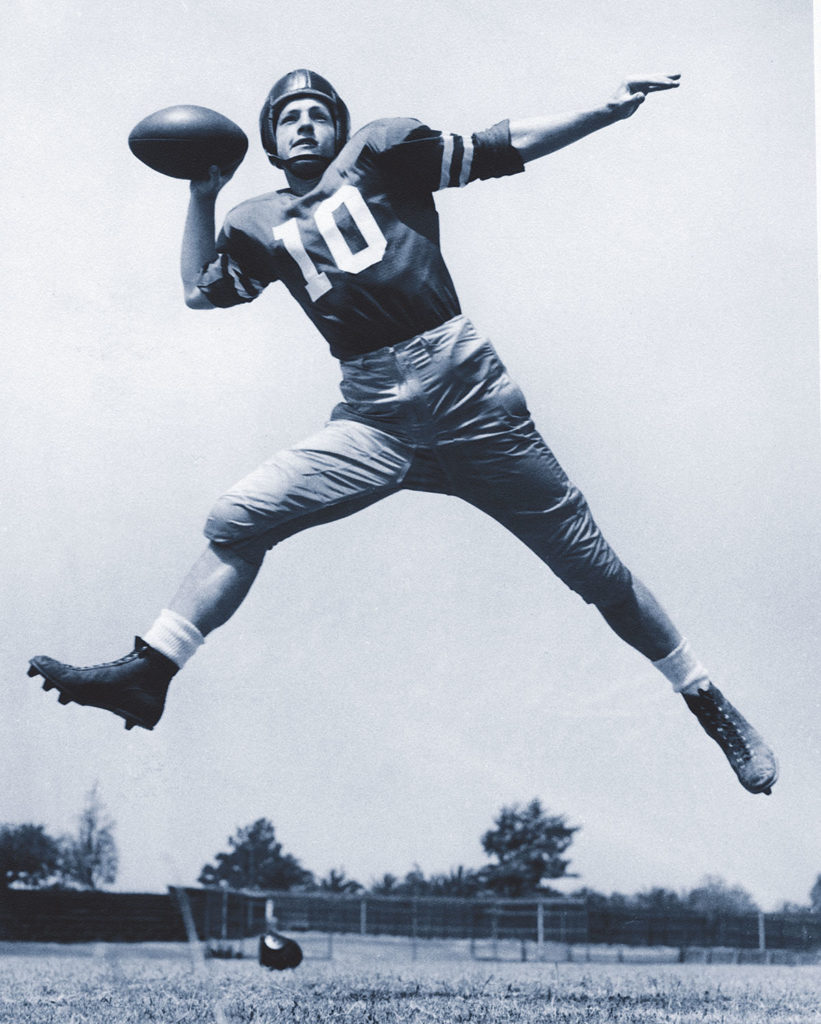

On January 12, 2016, National Football League owners approved the return of the Rams to Los Angeles. It was a day that the late Don Klosterman ’52 would have celebrated. After setting national records as Loyola’s quarterback, he carved out an equally illustrious career as an NFL executive. We asked former Los Angeles Times sportswriter Chris Dufresne, who knew and covered the Loyola University legend, to tell the Duke’s story as he saw it unfold.

No one would expect today’s “Snapchat” kids to remember.

Don Klosterman might as well be a fossil at the La Brea tar pits. The former Loyola quarterback and throwback bon vivant roamed a habitat where deals were sealed with firm handshakes and harder bourbon. High-speed technology was a rotary-dial phone delivered to your table at the Polo Lounge. Millennials probably don’t know Klosterman’s death in June 2000, at age 70, warranted front-page news in the Los Angeles Times: “A City Loses One of Its Best Friends.”

He was eulogized, in Sacred Heart Chapel, by Sen. Ted Kennedy, Frank Gifford, Bill Walsh and Al Michaels.

Don who?

If only his name rang a church bell. Go ask your granddad, or a Rams’ fan from the 1970s, or an LMU grad from 1952, or even me, who came to know Klosterman on the Bel-Air (Country Club) back nine of his career.

I last visited him in 1985, high above La Cienega Boulevard, in the Hollywood Hills. He lived in Cole Porter’s old house and seemed as comfortable there as a cigar in a humidor. I was a young reporter for the big-city newspaper, and Klosterman was a broken front-office man, having just presided over the dumpster-fire collapse of the Los Angeles Express and the United States Football League.

Approaching the compound (cue dramatic soundtrack) reminded me of the opening scene of Xanadu in “Citizen Kane,” another story about a lonely man in a fortress. The only difference was Cole Porter’s house was in Technicolor.

The USFL’s failure was not remotely Klosterman’s fault, yet he took defeat personally. This was the Loyola quarterback in him, the “Duke of Del Rey,” the competitive synapses from 1949 to ’51 still firing.

Like many athletes, Klosterman kept his hurt inside — and he hurt more than most. Pain had been his constant companion since 1957, when a near-fatal skiing accident led to last rites being administered three times.

A skiing accident, on New Year’s Day in 1957, wrecked his career. Told he would never walk again, Klosterman chucked a flower vase at his doctor.

Klosterman hated disappointing people, no matter their station in life. Even though he required a cane to get around, Klosterman loved kibitzing with Express employees on his long walk to his back office.

Klosterman was sickened to have been associated with an organization that left mom-and-pop venders holding bounced checks.

“To see creditors not being paid is sinful,” Klosterman told me at the time.

This was not the measure of the Loyola man who befriended his community and was reciprocally beloved, even by sports writers. Klosterman, in fact, served as a pallbearer at legendary L.A. Times columnist Jim Murray’s 1998 funeral.

The return of the Rams to Los Angeles, after the 20-year kidnapping by St. Louis, offers a chance to reflect on a pre-ESPN age when the Los Angeles Rams held court in the city square.

Klosterman was an integral cog in that heyday as Rams’ general manager during the roaring ’70s — ruling the roost as he hosted daily happy hours.

“He knew the mayor, the governor, the studio heads, the movie stars,” sports agent Leigh Steinberg says. “He had style and panache. His clothes were exquisite, his nails manicured, his cologne unmistakable.”

Everyone agrees: Hating Klosterman was almost impossible.

Steinberg and Klosterman had competing interests when, in 1984, they hammered out the then-preposterous $40 million contract for Express quarterback Steve Young.

Super agents don’t typically get swept away by upper management.

“Yet,” Steinberg says, “he drew you instantly into his web of friendship.”

Klosterman even invited Steinberg to the opening ceremonies for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. Steinberg says he was shocked to step into a town car that included Ethel Kennedy, Jane Fonda, Tom Hayden and Frank Gifford.

“He knew everybody,” Steinberg chuckles over the phone from his Newport Beach offices. “Anyone he met became his instant best friend. He was a raconteur, par excellence.”

Klosterman was the tactile type, a people-person who would have rejected the “Moneyball” wonks of today who think algorithms are the way to build championship sporting franchises. He oversaw the Rams to seven straight NFC West divisional titles, from 1973 to 1979, before the franchise slowly slipped into family-ownership dysfunction.

He was a hometown hero executive who ephemerally drifted — much like the Rams did when they left for St. Louis — out of our collective consciousness.

Posterity shortchanged Klosterman, in part because his Los Angeles moorings became a public television episode of Ralph Story’s “Things That Aren’t Here Anymore.” Loyola dropped football, the Chargers moved to San Diego, the Rams moved to St. Louis, the USFL folded.

You almost needed a notary and a witness to prove Klosterman, in 1951, led the nation in passing, completing 33 of 63 passes against the University of Florida. He was an All-America in a bygone era when small western schools like Loyola, Saint Mary’s, and the University of San Francisco played major-level football. If you can believe it: Only a 2-point loss to Santa Clara in 1950 denied Loyola a bid to the Orange Bowl. Loyola mothballed the program, though, as Klosterman was leaving it.

Klosterman’s pro career got short-changed when he had the unfortunate luck of being drafted by the Cleveland Browns, who employed legendary quarterback Otto Graham. The Browns then shipped him west to the L.A. Rams — uh, thanks a lot — to back up two superstars: Norm Van Brocklin and Bob Waterfield.

Klosterman sought refuge in the Canadian Football League, but a skiing accident, on New Year’s Day in 1957, wrecked his career. Told he would never walk again, Klosterman chucked a flower vase at his doctor.

Jim Murray once wrote that Klosterman “put more championship teams on the field than Knute Rockne.”

He crawled from his hospital bed to become one of pro football’s premier talent scouts and executives. He started in 1960 with the Los Angeles Chargers of the original American Football League. Klosterman followed the franchise to San Diego the next season, where his main job was prying top collegiate prospects from the rival NFL. His partner in early Charger crimes was a brash young upstart named Al Davis.

Klosterman later built the Kansas City Chiefs into an AFL power before being lured to the NFL by Baltimore Colts’ owner Carroll Rosenbloom. He helped Baltimore to a 1971 Super Bowl title and then followed Rosenbloom west to L.A. in 1972.

Jim Murray once wrote that Klosterman “put more championship teams on the field than Knute Rockne.”

Klosterman’s successful run with the Rams, however, was irrevocably altered after Rosenbloom’s drowning death in 1979. A family squabble put Klosterman in a political pickle between Rosenbloom’s wife, Georgia Frontiere, who inherited a 70 percent stake in the Rams, and her stepson, Steve. Klosterman was eventually forced out in 1982.

He summed it up to the Times at the time. “I stayed with the Rams because Carroll told me I had a lifetime contract,” he said. “Unfortunately, it was his lifetime, not mine.”

Klosterman resurfaced in late 1983 when he was hired to build the L.A. Express into a powerhouse so big it might someday get absorbed into the NFL. It would be just like the AFL — or so he thought.

Express owner J. William Oldenburg, a self-proclaimed billionaire known as “Mr. Dynamite,” gave Klosterman a blank check and a mandate. Klosterman spent $12 million on players, signing 31 of the nation’s top collegiate prospects. Two of those stars, Steve Young and lineman Gary Zimmerman, became eventual Hall of Fame players in the NFL.

The Express made it to the USFL playoffs in 1984 before the money well dried up. Oldenburg turned out to be a financial fraud, forcing the USFL to take over ownership. The Express never stood a chance, in part, because the league refused to replace injured players. The team lost 11 players to season-ending injuries in 1985 and finished 3-15. With no healthy running backs left on the roster, Young, the prized quarterback, played running back in the last game. The USFL fired Klosterman shortly before the team, and the league, folded.

Klosterman extracted every ounce of fun from life, yet strangely, he actually deserved to be luckier. It’s a shame more people don’t know the story of his rise from Le Mars, Iowa, as one of 15 children. The family ended up in Compton, of all places, but it was the place where Klosterman would continue to defy the odds.

Patrick J. Cahalan, S.J., LMU’s chancellor who presided over Klosterman’s funeral in 2000, captured his spirit in one sentence.

“I once invited Don to a retreat,” Cahalan said. “Don said, ‘I’m not retreating: I’m advancing.’ ”

Klosterman, no doubt, would have hosted a grand party to celebrate the Rams’ recent return.

And even if he seems more like “The Ghost of Del Rey” these days, well, didn’t he know all the haunts?

Chris Dufresne retired from the Los Angeles Times after 34 years during which he covered a variety of sports, including the USFL, NFL, golf, baseball, boxing and seven Olympic Games. For 20 years he was the paper’s national college football and basketball columnist. Dufresne has won numerous writing awards, including California Sports Writer of the Year in 2011. A Los Angeles native, he resides in Chino Hills, California, with his wife and three children. Listen to an LMU Magazine Off Press podcast episode with Dufresne about Don Klosterman <a href=”https://bit.ly/LMUmDufresne”>here</a>.