It was the perfect blend of philosophy, talent, conditioning and belief. The 1989–90 Loyola Marymount basketball team was an outlier, a tribute to its coach’s evolved trust in the running game and its players’ dedication to making that vision come to life on the court.

“I was always infatuated with fast-break basketball,” Paul Westhead said.

He coached the Lions for just five seasons: 1985 to 1990. His impact and the impact of the players he set loose on an unsuspecting college basketball world is felt to this day.

“I wanted to be the fastest team ever,” Westhead said.

He got his wish.

Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble transferred from USC, Corey Gaines from UCLA and Tom Peabody, a year later, from Rice University and Orange Coast College. Having transferred, they couldn’t play for a season, per NCAA rules.

“The year they had to sit out, they were destroying my varsity team at practice every day,” Westhead said.

• Listen: Paul Westhead on his Elite Eight team on the LMU Magazine Off Press podcast.

What changed everything, Westhead said, was his decision to go to a full-court press when all that talent was about to become eligible. LMU averaged 90 points per game the season before the press. They averaged 110.3 points with the press.

“It was the same fast break, different players and the different defense,” Westhead said.

The next season, LMU averaged 112.5 points. In 1989–90, it was an NCAA record then and now: 122.4 points.

“Ironically, people make fun of me all the time about my lack of defensive coaching ability; it was the defense that changed everything,” Westhead said.

That pressure led to turnovers that led to even more fast breaks on a shorter court with less defensive resistance.

“Everything that we did in terms of the style of play is the best scoring offense ever created,” Kimble said.

“I felt like i was one sock in the dryer, going around, around and around,” LSU coach Dale Brown said. “I thought had Paul Westhead stayed in college coaching, he would have revolutionized the game.”

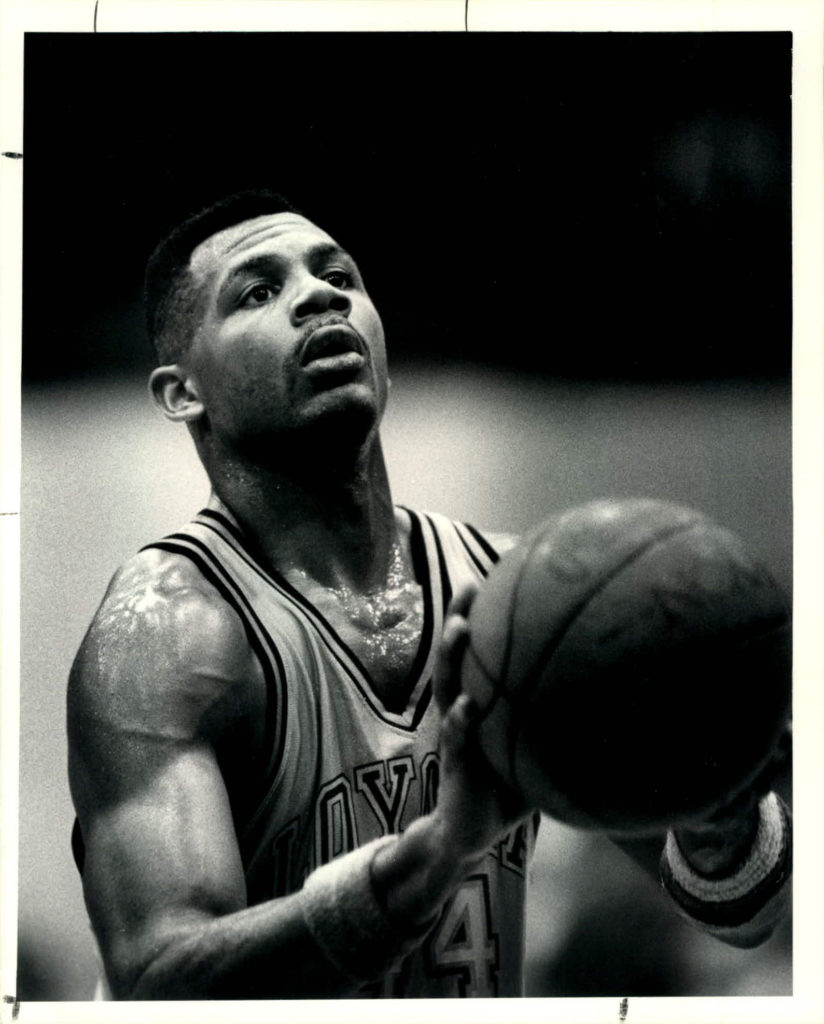

It was the press and the unceasing attack that wore teams out and led to February 1990 LMU scores of 150, 141, 157, 137, 139, 131, 123 and 117. It was the defense-to-offense transition that helped make Gathers the country’s leading scorer (32.7 points) and rebounder (13.7 per game) in 1988–89 and Kimble the country’s leading scorer (35.3 points) in the 1989–90 season that began and ended with games against eventual national champion UNLV.

“For the conference, I thought it was revolutionary,” said Miami Heat coach Erik Spoelstra, who saw it up close while playing for the University of Portland in the West Coast Conference. “Loyola Marymount was one of the first programs that took the conference to national prominence. It was nationally ranked and playing well against the better teams in America. … I think that set the foundation for Gonzaga to have the vision that they could also become a program that could be a nationally ranked powerhouse.”

That final season with “The System” will be remembered for its breathtaking basketball from coast to coast, the overwhelming sadness of March 4, 1990, when Gathers lay dying on the Gersten Pavilion court seconds after finishing an alley-oop dunk, and the inspiring run through the NCAA Tournament that got the Lions within a win of the Final Four.

“It really was an interesting time because my players and I really believed that we were doing something no one else had a clue about or could play against,” Westhead said.

The opener was at UNLV on Nov. 15, 1989. LMU was on an extended run late in the first half when the game was halted by a bomb scare that Kimble and Westhead are both convinced was a tactic because the Runnin’ Rebels simply could not keep up.

“It was obviously bogus, because they said, ‘Everybody look under your seat, if you see a brown bag, raise your hand,’” Westhead said. “It took all the energy and excitement away from us.”

In the second half, UNLV played a zone that LMU had not practiced against and won, 102–91.

Hank, Bo and their coach were Philly guys. Hank and Bo were the stars of one of the great high school teams in Philadelphia history at Dobbins Tech. Westhead played at St. Joseph’s University and coached at La Salle University.

LMU made a trip east in early January 1990, first playing St. Joe’s, a game Kimble won with a casual running 40-footer at the buzzer. Two nights later, the Lions gave La Salle its only loss of the regular season, 121–116, in a game unlike any in the wonderful history of Philly college basketball.

“It was like a perfect blend of speed, power, finesse and three-point shooting,” said Miami Heat head coach Erik Spoelstra. “Coach Westhead’s system was 30 years ahead of its time.”

Doug Overton, La Salle’s point guard and a high school teammate of Hank and Bo, said he was fine until the final two minutes.

“I was like, ‘This game is not going to end,’” Overton said. “I was done at the end of that game.’”

He thought he was ready for it.

“You grow up playing street ball and the personal connection with Bo and Hank. There was so much trash talk leading up to that game: ‘You guys ain’t ready for this.’ I’m thinking, ‘It’s basketball,’” Overton said. “Their philosophy was you can score, but you’re not going to be able to sustain it. You can’t prepare for a team that plays that way.”

And that was just the preliminary for Feb. 3, when LMU played at Louisiana State University on CBS. The score keeper’s electric typewriter could not keep up and blew out. They had to get a replacement.

Bo remembers Hank getting his first seven shots blocked by Shaquille O’Neal. Hank was not deterred. He was never deterred. He finished with 48 points and 13 rebounds. Shaq had 20 points, 24 rebounds and 12 blocks.

LSU won 148–141 in overtime.

“I felt like I was one sock in the dryer, going around, around and around,” LSU coach Dale Brown said. “I thought had Paul Westhead stayed in college coaching, he would have revolutionized the game.”

Brown won 448 games at LSU, but the one against LMU is the one everybody remembers.

“All these years later, people will come up to me in the damndest spots and say, ‘Coach, that is the greatest college game I ever watched,’” Brown said. “It really was. It was like gladiators going after each other in the Roman Coliseum.”

Brown made the decision his team would run with LMU, but his team paid a price for that strategy. One of his players, a backup named Randy Devall, was so exhausted Brown remembers him being doubled over on the court.

Wearing teams out was exactly what that LMU team was designed to do. The style has never been duplicated, but the impact reverberates to this day.

“It was like a perfect blend of speed, power, finesse and three-point shooting,” Spoelstra said. “Coach Westhead’s system was 30 years ahead of its time, trying to get layups, threes and free throws, essentially what the modern-day NBA is trying to manufacture right now.”

Guard Jeff Fryer still remembers what Westhead told him when the coach recruited him: “I’d have the green light to shoot whenever I wanted. I thought that was interesting.”

That might have been the greatest recruiting pitch in history. And it all came true.

The team was incredibly fast and impossibly fit. Point guard Tony Walker and forward Per Stumer completed the starting lineup with Gathers, Kimble and Fryer. Point guard Terrell Lowery, the fastest player on the team, came off the bench as did Peabody, Chris Knight and John O’Connell.

“The style of play was so dramatic,’’ current LMU coach Mike Dunlap ’80 said. “They were working the outer banks in terms of tempo, the three-point line, running and pressing. They don’t get enough credit on the defensive side of the ball.”

It has been 30 years, but nobody has forgotten how it felt and what it meant.

“Everything that we did in terms of the style of play is the best scoring offense ever created,” Bo Kimble said.

“Most teams went into halftime, their bodies, their muscles felt like they finished the whole game,” Kimble said. “They were the best days of our lives, that moment in time.”

Spoelstra remembers the feeling well.

“I have a picture where we were up at halftime at home, but the second half — it was uncanny: five, eight minutes into that half, all of a sudden your legs were gone,” he said. “And there was nothing you could do about it. As soon as your legs are gone, your mind quickly follows. And there would just be an avalanche from there. That game that we were up, we ended up losing by 30-plus points.”

Spoelstra also remembers how intimidating it was playing LMU. When his team arrived the afternoon before a game at Gersten and went to the gym for practice, he could see through the windows to the track.

“Out on the track, I see Gathers and a few of the guys doing sprints on the field with a parachute attached to them,” Spoelstra said. “It was crazy. We were beat before we even showed up.”

It was so exhilarating and then, in a moment, just as the NCAA Tournament beckoned, it was all so devastating.

LMU led Portland 25–13 with 13:34 left in the first half of the WCC Tournament semifinals when Gathers began to stagger and then fell at midcourt.

Hank’s funeral was held eight days later, a mile from where he went to high school in North Philly. It was devastating for the Gathers family, his teammates, friends and the entire LMU community.

After flying across the country for the funeral, the team somehow had to get ready to play New Mexico State in a first-round NCAA game in Long Beach.

Kimble had four fouls with 7 minutes left in the first half. Westhead kept him on the court. He had 35 points after the fourth foul and finished with 45 points and 18 rebounds. LMU won, 111–92. Kimble shot and made his first free throw left-handed in Hank’s honor.

“Chills would not describe what was going on; there was silence in the arena,” Westhead said. “People knew what was about to happen. You just hoped it would go in, not for Bo, not for LMU, but for Hank. I just can’t tell you what a sense of relief that was when it happened.”

Two days later, the Lions overwhelmed defending champions Michigan, 149–115, one final testimony to just how devastating The System really was. Fryer made a tournament-record 11 threes, still the standard.

Alabama slowed the game’s pace in the Sweet 16. But the Lions won anyway, 62–60, in Oakland. They lost to UNLV, 131–101, in the regional final, but the point had been made.

“I strongly believe if Hank had been alive, we would have won the national championship,” Kimble said.

That team, however, won so much more than games. They won hearts, minds and a special place in college basketball history.

There was nothing like them before; there has been nothing like them since.

Dick Jerardi covered college basketball and horse racing for the Philadelphia Daily News from 1985 to 2017. He reported on 25 NCAA basketball Final Fours, and in January 1990, he covered LMU’s games vs. La Salle and St. Joseph’s in Philadelphia. This article appeared in the winter 2020 issue (Vol. 9, No. 2) of LMU Magazine.