I had a writing professor many years ago who complained that Catholics had an advantage when writing fiction: The moral absolutes of their faith created an artistic tension which another modern author might have to manufacture out of whole cloth. The literary protagonist who seeks sainthood and dreads damnation is a bit more interesting, after all, than the one who just looks for ways to stop being so bored.

Graham Greene was his prime example of a writer who could give to his characters any number of doubts and failings and interesting side trips along life’s journey, because they inevitably bumped up against the bulwark of the Church — in its teachings and beauty, but foremost in its absolute certainty that God had granted it the authority to forgive sin. Greene himself had a complicated relationship with the Church; he often called himself a “Catholic agnostic” and, according to his biographers, never quite got the hang of some of the rules around the naughty bits of life, as was the case with many of the characters in what are called his Catholic novels: “Brighton Rock,” “The Power and the Glory,” “The Heart of the Matter,” “The End of the Affair,” and “A Burnt-Out Case.”

What if a plea for forgiveness is evidence of the good still to be found in the penitent?

My professor wasn’t a Catholic, obviously, or he would have known that most of us go out of our way to avoid being forgiven for our sins because we can’t bear to go to Confession. But he did have a point about Graham Greene and sin and forgiveness — and maybe about Karl Rahner too. (Okay, my professor had surely never heard of Karl Rahner, but we’re talking about fiction here anyway, and surely it’s not always a sin to tell a lie?)

In “The Power and the Glory,” the dissolute “whiskey priest” around whom the novel revolves meets a pious woman in a Mexican jail cell full of thieves, drunks and fornicators. Her only crime is possessing religious images, but her complaints about the evils of their fellow prisoners make it clear she holds her own tribunal of the sins of others in her head — while ignoring her vain appraisal of her own holiness. It’s not fair, she tells the priest, that evil people should be forgiven while good people are punished. He demurs, gently, and later we find out the reason why.

Near the close of the novel, the whiskey priest hears the confession of a murderer and lifelong criminal whom he suspects (correctly) is part of a plot by the authorities to capture the fugitive priest — luring him in with the tempting possibility of saving the man’s soul. It seems an act of madness: Who would believe such a person? But the priest recognizes that a deathbed confession, what some might sneer at as a “get out of Hell free card,” is not always such an easy thing. The desire for forgiveness is not something that automatically wells up in the hearts of the wicked. Here is Greene:

The priest sat hopelessly at the man’s side: nothing now would shift that violent brain towards peace: once, hours ago perhaps, when he wrote the message — but the chance had come and gone. … He had heard men talk of the unfairness of a deathbed repentance — as if it was an easy thing to break the habit of a life whether to do good or evil. One suspected the good of the life that ended badly — or the viciousness that ended well.

Who knows, in the end, the balance of good or the evil that lurks in another’s heart? A tally of our sins doesn’t quite tell the whole tale. The great Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner suggested something similar in the 1960s, that we might be better off thinking of our lifelong response to God’s grace as a “fundamental option,” an overall orientation toward God and what is good, rather than an accountant’s ledger of our many sins. What if a plea for forgiveness is evidence of the good still to be found in the penitent?

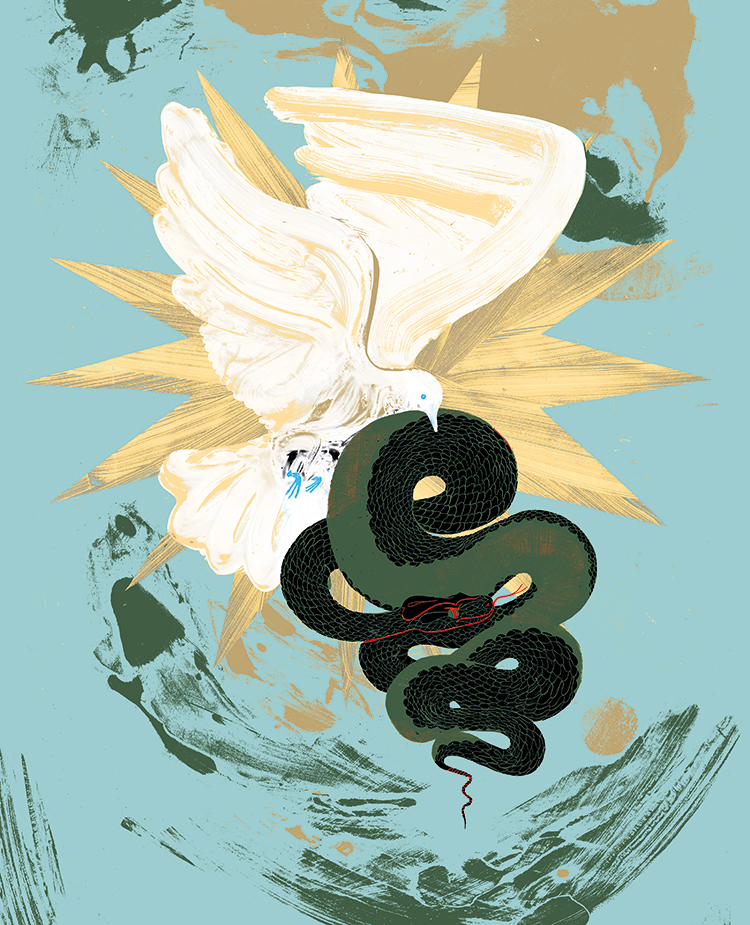

Note that the language of absolution in the Rite of Reconciliation stresses that “God, the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son, has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins.” That last bit is important, because there is only one sin that Jesus calls unforgivable: the “sin against the Holy Spirit.” And what is that sin? Despair. The deliberate refusal to believe in the mercy of God, in the possibility of pardon.

I think Graham Greene fancied that his whiskey priest and his penitent murderer, bad men by most accounts, enjoyed paradise — along with the repentant thief in the scriptures who was crucified along with Jesus. Like Greene himself, they might have doubted, but they never despaired.

James T. Keane ’96 is senior editor of America magazine. Keane’s writing has appeared in Philadelphia Weekly, U.S. Catholic, Busted Halo and elsewhere. His “The Bones of St. Peter” appeared in the summer 2021 issue of LMU Magazine. Follow him @JamesTKeane.

Romy Blümel is an illustrator based in Berlin, Germany, and a member of the female artist collective “Spring” founded in 2004 in Hamburg. Her clients include The New Yorker, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Goethe Institut, Yale University Press and Financial Times. Follow her @RomyBluemel.