After several mass shootings in late spring 2022, including in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo, New York, the U.S. Congress passed gun control legislation involving background checks, red flag laws and other measures. The measures represented moderate steps, and rare, since they were passed after decades of congressional inaction. Almost simultaneously, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled New York gun laws, loosening restrictions on citizens’ ability to carry concealed and loaded weapons in public. We asked LMU’s Evan Gerstmann to discuss the history of the Second Amendment to the Constitution and the Supreme Court’s interpretations of its meaning. —The Editor

What is the text of the Second Amendment?

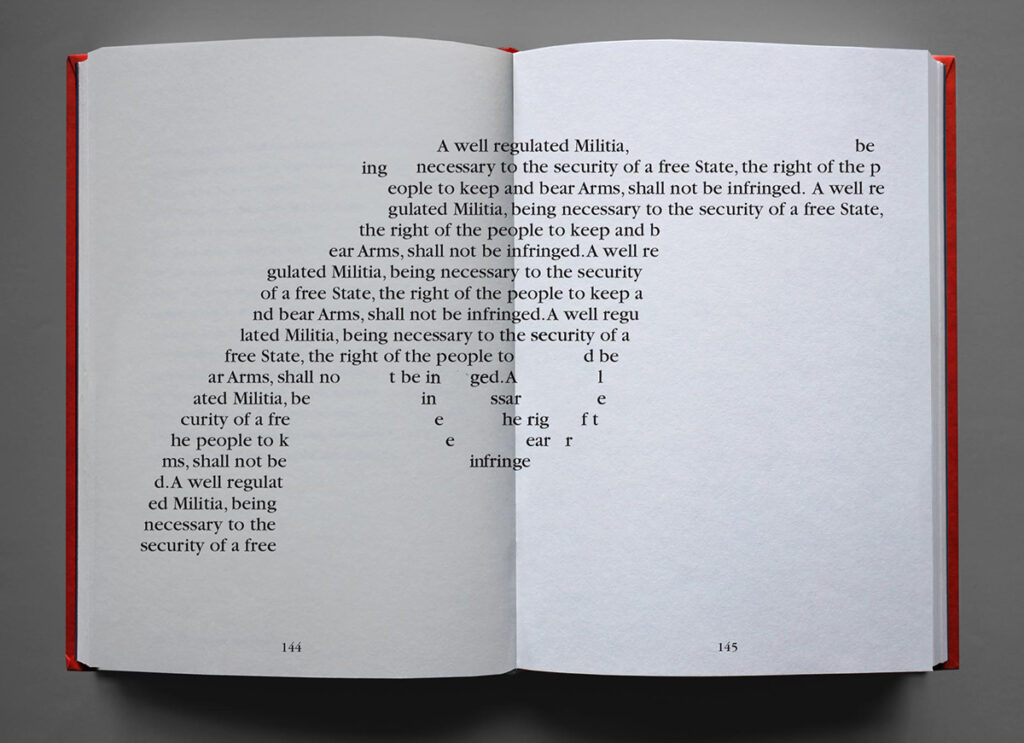

“A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

Why were gun rights considered a subject appropriate to address in the Bill of Rights?

James Madison argued in The Federalist Papers that state militias would be a guardrail against federal tyranny. He wrote that a tyrannical federal government “would be opposed [by] a militia amounting to near half a million of citizens with arms in their hands, officered by men chosen from among themselves, fighting for their common liberties.” The Framers were also influenced by the English Common Law of the time, which included a right to self-defense.

Did the framers include the Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights to permit owning guns for self-defense or to allow citizens to possess arms in case they were needed to come to the aid of the government when facing a foreign threat?

The Framers had diverse thoughts on this. They were concerned about self-defense, foreign threats and domestic tyranny.

When did the Second Amendment begin to be interpreted in the context of individual rights?

At the level of the Supreme Court, not until 2008 in a case called District of Columbia v. Heller. Until then, it was generally thought that the states have a right to a militia and that the right to bear arms was only violated to the degree that a law prevented states from having such militias.

Were there earlier periods in U.S. history when the scope of the Second Amendment was intensely debated? For example, was the amendment an issue during the post-Civil War era when the federal government may have wished to limit gun availability in the former Confederate states?

During Reconstruction many Southern states sought to disarm African Americans, but this was opposed by Congress. The Supreme Court majority in the Heller case argued that Congress’ position then demonstrates that the right to bear arms is an individual right not reliant on serving in a state militia.

Did the 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller decision follow on previous decisions or was it a relatively novel decision on the part of the court?

The Heller case seemed to come out of nowhere, although that doesn’t mean that it was wrongly decided. The last Second Amendment case before the Supreme Court was in 1939, U.S. v. Miller, which upheld the power of the federal government to ban weapons such as short-barreled shotguns.

Since the Supreme Court often refers to historical tradition in grounding rulings, is it contradictory for the court to interpret the Second Amendment in ways unspecified by the nation’s founders?

The court denies that they are doing this. They argue that the “right to bear arms” is the operative clause of the Second Amendment, while the “well-regulated Militia” clause is merely “prefatory.”

How influential have groups like the National Rifle Association been in framing interpretations of the Second Amendment?

I would say that the National Rifle Association has been more influential in the legislative process than with the Supreme Court. They do endorse pro-gun state judges and prosecutors, but federal judges are not susceptible to that sort of pressure. At least until now, the lack of legislative will has been a far greater obstacle to meaningful gun safety laws than the Second Amendment. The court has not prevented popular measures such as universal background checks, age requirements for powerful weapons, safe-storage laws or laws to prevent gun-running.

Families of victims of the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School mass shooting in Connecticut sued the Remington Co., which makes AR-15s, resulting in a $70 million settlement in February 2022. Does the Sandy Hook settlement suggest that gun manufacturers will face increased financial liability in the future for how guns are used?

The case was based on a theory of negligent advertising so the only area where it might do some good is in preventing marketing of guns in ways that encourage violence. The advertising for the “Bushmaster” rifle used in the Sandy Hook shooting was pretty infantile. For example, the company’s website read: “In a world of rapidly depleting testosterone, the Bushmaster Man Card declares and confirms that you are a man’s man.” So, the fact that the suit was able to proceed and produced a large settlement will probably mean that gun manufacturers’ lawyers will look more carefully at that kind of marketing.

Does the Court’s June 2022 ruling in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen that overturned New York gun laws dramatically reshape gun rights in the U.S.?

Very much so. I try to stay away from hyperbole, but New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen is a game-changer. In one fell swoop, it overruled an entire jurisprudence that had built up by numerous federal appellate courts over time. Those courts created a two-step process that allowed courts to take the interests of states in public safety into account while weighing that interest against the degree of burden that a law placed on the right to gun ownership. But the Supreme Court held that “Despite the popularity of this two-step approach, it is one step too many.” Gun control laws will now be struck down unless “the government [can] affirmatively prove that its firearms regulation is part of the historical tradition that delimits the outer bounds of the right to keep and bear arms.” That’s big stuff. Normally, if the government can show that a law is “narrowly tailored to further a compelling government interest,” that law is constitutional. Now, even narrowly tailored laws violate the Second Amendment unless they are part of a “historical tradition” of gun regulation such as protecting sensitive places such as schools and courthouses. This could have terrible results. For example, there are states that don’t even require gun stores to have burglar alarms. Gun store robberies are an important way that guns get into the hands of criminals via the black market. Asking whether laws requiring gun stores to more safely store their guns is part of the nation’s “historic tradition” seems like the wrong question. Laws that promote public safety without significantly burdening the right of law-abiding citizens to bear arms should be upheld even if such laws weren’t common when the Second Amendment was ratified.

Is it the case that the current Supreme Court is displaying a form of judicial activism that some of its members have criticized in the past?

Yes, this is a very activist court. I’m not prone to these sorts of pronouncements — I wrote a piece for the Loyola Law Review in 2013 arguing that the court wasn’t nearly as conservative as its critics were making it out to be. So, you can take it from me that this is a very activist court. By that, I mean that it consistently makes big constitutional rulings that go well beyond what is necessary to resolve the case in front of it and does so in way that consistently promotes the political ideology of the presidents who appointed them. Examples abound. The New York State law at issue was poorly drafted and gave far too much discretion to state officials to decide who needed a conceal carry permit. The Court could have easily struck it down for that reason. And the court overturned Roe v. Wade even though, as Chief Justice John Roberts pointed out, it could have upheld the law at issue without getting rid of the right to abortion altogether. Now, even rape victims have lost the right to an abortion, which is a very drastic result. And the court also upended a major legal doctrine in the area of the Religious Establishment clause when it didn’t need to in order to resolve the case. And this was all in one week!

Evan Gerstmann is professor of political science and international relations in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. He is the author of three books, including “Campus Sexual Assault: Constitutional Rights and Fundamental Fairness” and “Same-Sex Marriage and the Constitution.” He teaches courses on constitutional law at the undergraduate and law school levels.