A photo of a funeral: A family of eight, clustered around a grave. Long-stemmed white roses on exposed earth. Grief is universal, of course, but in this image I felt a difference in culture. The women were in black, and their heads were covered in scarves. The grave was a dirt mound, and the people were practically atop it, clustered together. What struck me is that they were plain in their suffering, mourning in a way that somehow felt different — ancient, perhaps. Decorum be damned. One look at the photo and you knew there would be wailing.

There were two reasons I was drawn to this image: First, I realized how much I didn’t understand. What was cultural and what was particular to this family? And second, this photo was of my family. In the ground was my uncle. Around him were my cousins. A life lived on separate continents, and I felt the distance even in my curiosity.

Growing up, it was as though I’d slipped between the cracks. My entire existence, stuck in a place between two others. My mother is 100 percent Flemish and from Minnesota. My father is 100 percent Kurdish, from Iraq. Even their names — one begins with an A, and the other with a Z. From the start, I was to live between extremes.

I was born and mostly raised in Los Angeles. Dark hair and dark eyes, it was clear I belonged to my father. But that was where much of the feeling of belonging stopped. When I was 5, we went to Iraq. I was the American come to visit. The children followed me, curious. Interactions with my grandparents involved a lot of grinning and cheek-pinching, as we didn’t speak the same language. When I did say words in Kurdish, they smiled and laughed. At the time, I thought it meant I’d bungled the pronunciation, but now I realize it was that joy from the love of attempt, the happiness you feel when someone tries to reach you.

Visiting my grandmother on my mother’s side was the other extreme, and yet in Minnesota, too, I was an outsider. A family of farmers, a people used to hot dishes and harsh winters. I was the California child, but I lacked the blond hair and blue eyes that even my Minnesota family had. Walking with my grandmother, one had only to glance at us to know we were not from there. On farms, we craned our heads at common sites and ran from things that were not frightening. My cousins laughed.

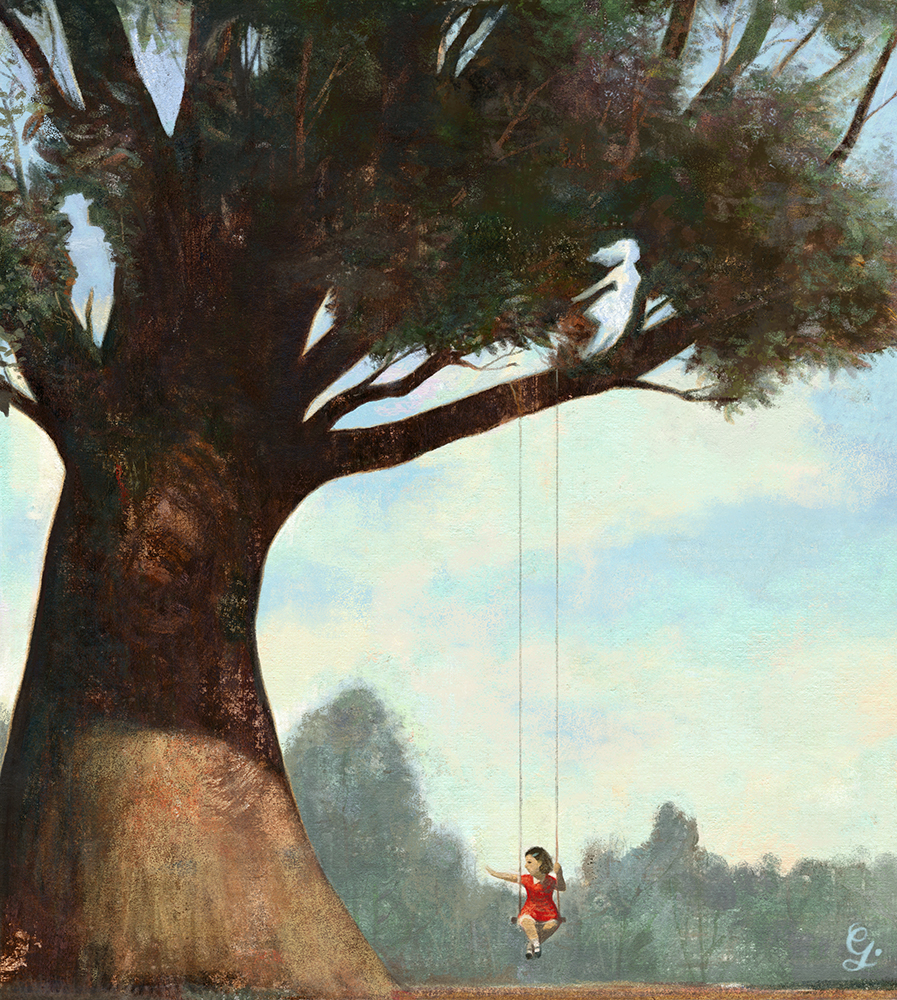

Of course, all immigrants — and all parents, in general — have children who struggle to understand their lives. A child of someone from a different country, a different state, a different religion, a different way of life. We are always the next branch on the tree and never do we look the same. But the difference is in the details, and those I became finely attuned to. I tried to understand. I observed. The questions I had and the longing to know forced me to pay attention, to remember stories and jokes that were told, or to study the table of “salads” that involved more Jell-O than lettuce and the way tea was poured from a samovar. My role as observer has never ended. I am the person at the edge of the room. I am the one listening to the stories. I am the writer, the ultimate eavesdropper, the one taking notes. Was it nature or nurture that led me down this path? Do I long to lean in closer simply because I’d always experienced an inherent distance? Perhaps it doesn’t matter.

My novel “You Were Here” takes place in Minnesota and mostly in the past, and in it are the connections not just to my life, but to my mother’s. After all, I never lived in Minnesota in 1948, but she did. As did my grandmother. And though I don’t know where my current project is going, or if it will go anywhere at all, I will say this: It draws upon my father’s world. Perhaps in a sense these works are excuses to feel a part of worlds I never got to experience. Trust in what you’ve been given, my mother used to say. And though it was hard, often feeling left out of my own family, I see what it has brought me, and what once felt like a handicap has, I hope, become my greatest gift.

Gian Sarder, who studied English in the Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts, is the author of “You Were Here,” a novel, and co-author with Sarah Lassez of “Psychic Junkie,” a memoir. Learn more about her work here.