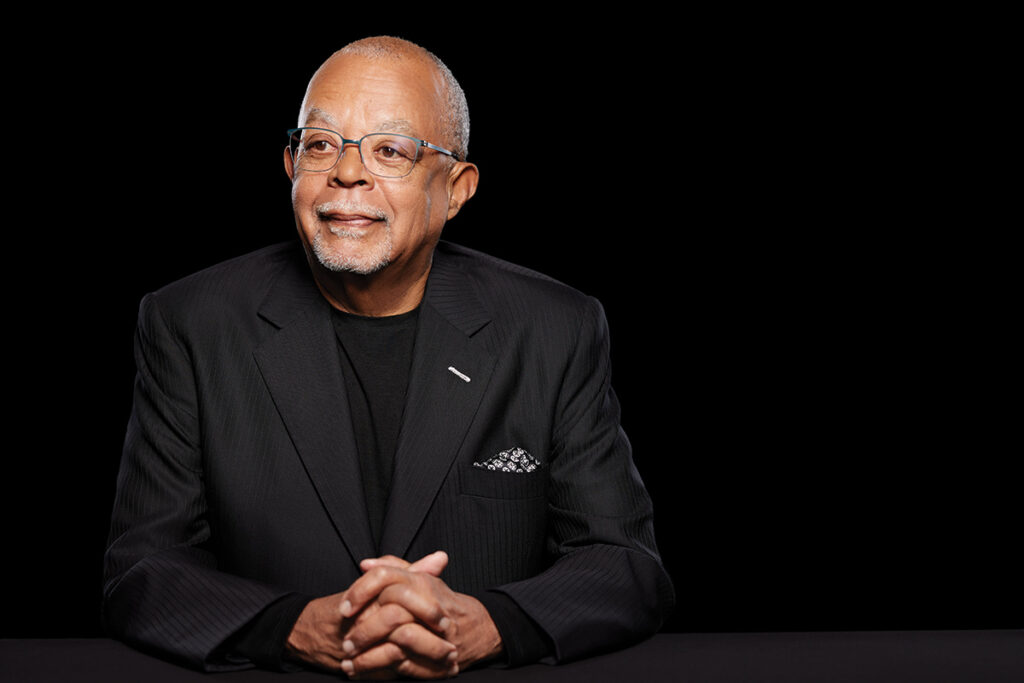

Henry Louis Gates Jr. is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University. He is the author of many books and host of the PBS series “Finding Your Roots.” Among his documentaries are “The Black Church” and “Frederick Douglass: In Five Speeches.” Gates has consulted on the College Board’s AP African American Studies course, and he has been host of LMU’s Global Conversations series with thought leaders and commentators. Gates was interviewed by Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch.

The effort to censor or even shut down the teaching of Black history is widespread in America. Why do you think so much of white America is afraid of Black history?

I’m not sure how much of white America is, in fact, afraid of Black history. I think this attempt to censor the teaching of American history in its full range of colors, let’s say, is limited to a few political opportunists, as we see in Texas and Florida. Given the popularity of my documentaries on PBS, I don’t see a national trend in censoring the telling of the complex history of race and people of African descent in America. “Finding Your Roots” is the No. 1 show on PBS. It has over 4 million viewers a week. Most of our viewers, by definition, since it is PBS, are white. Many of the stories involve people of color. My experience in public television runs counter to the assumption that Americans aren’t interested in complexity when it comes to understanding how our great country was formed and how it evolved and how it got to where we are today.

I think people like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis aren’t afraid. I think they’re manipulating imagined fears of people in order to make themselves popular with an electorate. In other words, they’re inventing a narrative that is not being told and claiming that this is what people like me as professors of African American studies are trying to ram down the throats of their children. It’s disgusting. There may be some extremes here and there, as in all cases. But, by and large, people teaching the story of African Americans and the story of race in this country are middle-of-the-road, good-hearted people who just believe that it’s important to expose students to the facts.

In the face of false narratives, what’s your obligation?

The obligation of the scholar or the artist determined to implement a meaningful definition of multiculturalism in the classroom is to tell a good story. The obligation of us as political actors is to insist that school boards do not engage in political censorship because they’re baited by greedy, manipulative politicians who are trying to rule by fear and profit from those fears on election day. So, we have to stand up for freedom of expression. The most important thing we can do is insist on the free exchange of ideas in the classroom, whether that’s elementary school, middle school, or high school.

Some people would say the power of true storytelling is stronger over time than contemporary efforts to censor history, such as we’ve seen in decisions by the Florida Department of Education. In the long run, truth comes out. Even so, the impact of legislative attempts to control how history is told is serious and extensive. Do you worry about that impact?

I think the practice of censorship in Florida is disgusting. Censorship is to scholarship and the pursuit of knowledge as lynching is to justice. It is never justified. What’s happening in Florida is Ron DeSantis wants to be president of the United States, and he’s taking the low road to get there.

I would be more worried, to tell you the truth, if it weren’t for the Internet and the media. How much time does a student spend in an American history classroom? An hour? How much time does a student spend on the internet in a day? Eight hours, 10 hours? They have access to all of Ken Burns’ documentaries, my documentaries, “60 Minutes,” HBO, and Netflix just with a click. They have access to other narratives. I think that DeSantis has made them more curious about what’s being excluded than they would’ve been if he had kept his mouth shut. The quickest way to get a student to read something is to tell her or him that they shouldn’t read it. They think, “I wonder why I shouldn’t read it.” Still, in spite of tremendous access to knowledge that we have today, what’s happening in Florida and to a less publicized extent in Texas and other places, is simply disgusting. And those of us who love the pursuit of truth and knowledge have to stand up against it.

“Censorship is to scholarship and the pursuit of knowledge as lynching is to justice. It is never justified.”

In the 1960s, a major battleground in U.S. race relations was voting rights. Today, the battleground appears to be education. Though the battleground appears different, is the battle itself the same?

Incredibly, we’re still engaged in a battle over voting rights because of the attempts of elements of the Republican Party to suppress the Black vote in majority-Black districts. The Black American community right now is overwhelmingly voting Democratic. We have to be ever-vigilant and spend our time fighting the rollback of Affirmative Action and the suppression of the vote. That’s important because that’s how Reconstruction ended.

What does the Reconstruction era have to do with this?

When the Reconstruction started, nine out of 10 Black people lived in the former Confederacy. That meant that Black male voters — remember, only men could vote — had a tremendous amount of power. South Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana were majority-Black states. Georgia, Alabama, and Florida were almost majority-Black states. So, concentrating the Black male vote for one candidate could sway an election. And, in fact, it did. So, the alarms went out and the former Confederates regrouped and came back in 1890 with what was called the Mississippi Plan, which effectively disenfranchised almost all of the Black male voters in the state. I’ll tell you how effective it was: In 1898 in Louisiana, there were 130,000 Black men registered to vote. By 1904, that number had been reduced to 1,342. That was due to poll taxes, literacy tests, and the grandfather clause, which restricted the right to vote to men who could vote prior to 1867 or whose ancestors could. It was pernicious. Which is why one of the main thrusts of the Civil Rights movement was registering Black people in the South to vote, because they hadn’t been able to vote since the 1890s.

That’s a very important lesson, and it’s important to teach about the Reconstruction Era. Reconstruction is the period immediately following the Civil War in which Black people exercised more rights than any other group of Black people have in any point in American history. And within 20 years, it was all taken away.

I made a TV series called “Reconstruction: America After the Civil War” as soon as I saw the reaction across America, sadly, to the election of Barack Obama. I remember the hope and optimism. Obama was leading us to the promised land. “A Promised Land” is how he titled his book. What he didn’t know was that waiting in the promised land was the beast of white supremacy who was kicked awake by his election. Much to my horror, rather than inaugurating a new era in race relations, the election of Barack Obama inaugurated a racist, reactionary rollback leading to the election of Donald Trump. A black man in the White House stirred all of these slumbering fears, and a demagogue tapped into those fears, just as under Reconstruction. Which is why it’s important to tell the full story of American history, so that people are aware that Donald Trump is Redemption Redux — Redemption was the period following Reconstruction when the South “redeemed” itself by reinstituting slavery and instituting white supremacy as the law of the land in the South. And the North let them do it. And we should never forget that the North allowed them to do it.

“Much to my horror, rather than inaugurating a new era in race relations, the election of Barack Obama inaugurated a racist, reactionary rollback.”

A common image often applied to America is the “city on a hill” — the place that God ordained and the apex of human civilization. Another is America as Original Sin — slavery is our original sin, it’s here, it’s indelible, and its impact will always be with us. Can these two metaphors be reconciled, can they live together, or will we be pulled between them for the rest of our country’s history?

I say both things are true. The prosperity of the United States of America was directly dependent on the exploitation of free labor, and that free labor was, alternatively, Native Americans for a period and then overwhelmingly people of African descent. That’s a fact. Slavery is coterminous with the creation of the United States. No one can argue that. My friend Nikole Hannah-Jones has done much with her 1619 project, but the truth is African enslaved people arrived in Florida a hundred years before. We’ve had slavery present in Spanish America and British North America for 500 years. So it’s very difficult to say or imagine what America would be without the presence of slavery, because slavery was so fundamental to its evolution, to its attitudes about race, citizenship and land ownership. And land ownership was directly connected to who could vote, because initially only white males who owned land could vote.

Original sin is one metaphor. I prefer, since I’m a student of DNA analysis, to say that slavery is part of the DNA of the United States. What does that mean? Genes can be present and not expressed. You need gene expression for genetic potential to be manifest. So, to say that racism is part of our DNA doesn’t mean that we are inevitably doomed to be racist. Racism is there, just like ant-Semitism is there. The question is: Are we going to resist the urge to exploit the historical uses of anti-Semitism? Are we going to resist the urge to exploit the historical uses of anti-Black racism? Or, are we going to be like Donald Trump and say, “No, I’m going to build my entire campaign on the exploitation of anti-Black racism and xenophobia” — fear of the other, which is also part of the DNA of American history and culture.

This is why teaching a truthful, whole story is important — how the United States was slow to defend the Jews in Europe, and turned away a ship of refugees, how Asians were put in concentration camps during World War II when German Americans were not. Or why Cuban immigrants are welcomed more readily than Haitian immigrants today. It’s important that we expose students to a three-dimensional history of American history so they can be better citizens, so that they can say, when a demagogue like Donald Trump is trying to manipulate their fears, “Oh, we’ve been here before, and I’m not going to be seduced by that siren song. I know it’s evil because someone tried it in the 1930s, and the 1890s, and 1830s.”

In the 1960s, it was hard to imagine a future without wars. But it was not hard to imagine an America in the future that had made a lot of progress in race relations. Many people thought we would’ve made much more progress by now. Is that being too pessimistic? Or do you think we’ve made significant progress?

Things are definitely better in this country about race relations than they were 50 years ago. The benefits of Affirmative Action can be measured by the number of Black people in the middle classes and the upper middle classes. The Black middle class has doubled, the Black upper middle class has quadrupled. Look at the Black people in courtrooms, on Wall Street or walking around the campus of LMU. The class of 1966 at Yale had six Black graduates. The class of 1996, my class, had 96. Affirmative Action mattered. The power structure in America is of a different complexion today that it was 50 years ago.

But it’s almost as if when Obama’s election kicked awake the slumbering beast of white supremacy, people looked around and said, “How did all these Black people get in here?” That’s why good people all across the color spectrum in America need to join hands and fight tyranny, injustice, demagoguery, race-baiting, and anti-Semitism that we see on the rise throughout American society

How to Find Your Own Roots

For 10 seasons, Henry Louis Gates Jr. has hosted “Finding Your Roots,” a PBS series that explores the genealogical background of well-known guests, such as John Lewis, Tina Fey, Ken Burns,

Bill Hader, Nina Totenberg, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Rosanne Cash, Lisa Ling, George R.R. Martin, Paul Ryan and many others. Since we can’t all be featured on the show, we asked Gates for tips about how to begin researching one’s family history. —The Editor

If you want to start locating your ancestors, “finding your roots,” go to one of the portals, such as Family Search or Ancestry.com, which is subscription-based and — full disclosure — a lead sponsor for “Finding Your Roots.”

Just type in your name and the name of your parents or grandparents, and these sites will connect you to all of the documents with that identical name. You also should take a couple DNA tests. All of our guests on “Finding Your Roots” are tested by 23andMe and Ancestry.com, because those companies have distinct databases. They connect you with anyone who is your cousin, as defined by the fact that you share long identical segments of DNA. That’s the only way to begin.

I warn you: It’s addictive.

Then, every major city, more or less, has a genealogical society. Salt Lake City has the Family History Library. In Boston, there is the New England Historic Genealogical Society. You can walk in off the street and someone will help you get started tracing your family tree. Or you can go online and hire a genealogist, if you have enough money. Usually they ask for a retainer. They’ll say, “This is what we found, and if you want to know more it’s going to cost you this amount.” So, costs range from free to $99, all the way up to thousands of dollars. But don’t write to me and ask me to do your family tree, because I’m not going to do it! People write me all the time, “Hey, would you do my family tree?” “Oh, yeah, I’m sitting around, not doing anything!” But I answer all the letters, and I tell people how they can start. —Henry Louis Gates Jr.