When people describe 1968 as perhaps the most tumultuous year they remember, believe them. It’s true. The Soviet Union sent troops to Czechoslovakia to smother a political reform movement there. In Mexico, the military fired on and killed student protesters days before the summer Olympic Games began. Chicago was awash in riots during the Democratic Party convention, and the U.S. was mired in the Vietnam War. And Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated.

While the 1968 presidential race is often thought of as a war election, it marked the undeniable success of the Southern Strategy, a GOP strategy to gain support among Southern whites, pulling them from the Democratic Party. That election also cemented the place of Black voters in the Democratic Party.

Although the impact of the Southern Strategy on the ’68 election is recognized, less so are its ongoing effects, which helped create America’s hyperpolarized politics of today. To understand why this is so, we must hop into the “wayback machine,” and see how white and Black American voting patterns developed and hardened over the years.

While the 1968 presidential race is often thought of as a war election, it marked the undeniable success of the Southern Strategy, a GOP strategy to gain support among Southern whites.

At the end of the Civil War, with Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, slaves became free citizens (in name only) and credited President Lincoln, a Republican. His assassination cemented for most newly freed slaves a devotion to Lincoln. With the 1870 passage of the 15th Amendment guaranteeing former slaves the right to vote, they overwhelmingly supported Republican candidates.

The first shift in Black support for Republicans occurred during the Great Depression presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. FDR’s New Deal marginally helped Black Americans, and some shifted loyalties to the Democratic Party.

But it wasn’t until the 1960s that a transformation in Black voting — and white voting — occurred. In the 1960 presidential race between Democrat John F. Kennedy and his Republican rival Richard Nixon, Kennedy won two-thirds of the Black vote, enough to eke out wins in several key states. The Black vote tipped the scales for Kennedy.

For Black voters, 1964 was a watershed election. The Republicans nominated Arizona’s Sen. Barry Goldwater, who was seen as a “states rights” candidate (a code word for anti-Black). After the election, over a third of Black Republicans switched parties.

Then came the revolution! Lyndon B. Johnson passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. LBJ knew that promoting civil rights was risky and that it threatened the Democratic hold on the “solid South.” But he insisted there was a “moral” requirement for the U.S. to act, opening the door for the Republicans to exploit a political opportunity.

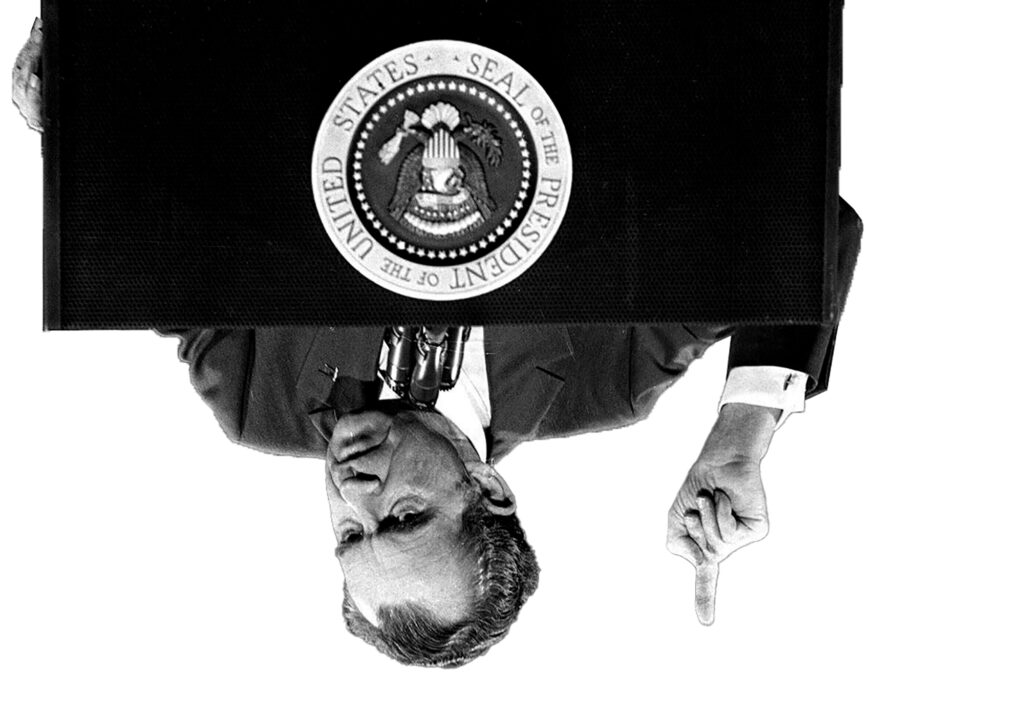

In 1968, Nixon again was the Republican presidential nominee. And while the ’68 election focused primarily on the war in Vietnam, he saw the rumblings of Southern Democrats who were livid that LBJ “forced” segregation on the South, pushed for school integration, promoted Black voting, and threatened their hold on power. Nixon seized the opportunity, developing the Southern Strategy. He was determined to use the resentments and anger of Southern Democrats to “convert” them to the Republican Party. To do so, Nixon had to rebrand the party into an anti-civil rights party. He did so by nominating ultra-conservative Southerners to the Supreme Court, practicing “benign neglect” of minorities, and shifting federal policy away from civil rights enforcement.

From then on, Southern Democrats shifted to the Republican Party, and Black voters migrated to the Democratic Party. This split is evident in voting patterns from past presidential elections. In the past five presidential elections, over 90 percent of the Black American vote went to the Democratic candidate, this as white citizens voted for the Republican candidate in roughly a 60-40 percent ratio. The Southern Strategy worked, and it reshaped our politics. We continue to be a divided nation, divided by urban-rural differences, racial differences, religious-secular differences, and a host of other issues that drive us apart. For how long can we continue to be a “house divided against itself”?

Michael A. Genovese, a frequent contributor to LMU Magazine, holds the Loyola Chair of Leadership at Loyola Marymount University, where he serves as president of the Global Policy Institute. He teaches in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts and is the author of more than 50 books. In 2017, Genovese was awarded the American Political Science Association’s Distinguished Teaching Award, only the fifth time in APSA history that the honor has been awarded.