The Harden Gate stands sentinel at a scenic, perilous curve of the road that circles the edge of Palos Verdes Peninsula. To the west, down the cliff, nestle the sea caves and tide pools of Abalone Cove. Across and up the street rises the redwood, glass, and stone steeple of Lloyd Wright’s Wayfarer Chapel. To the southeast lies the geologically unstable ravine of Portuguese Bend. I often drive by here on my way home to San Pedro from work in Westchester on evenings when I choose the ocean views over the stacked brake lights on the 405. I long wondered what lay behind the towering wooden doors of Portuguese Point, as I prepared my stomach for the roller-coaster ride up and down the ever-shifting soil just around the bend.

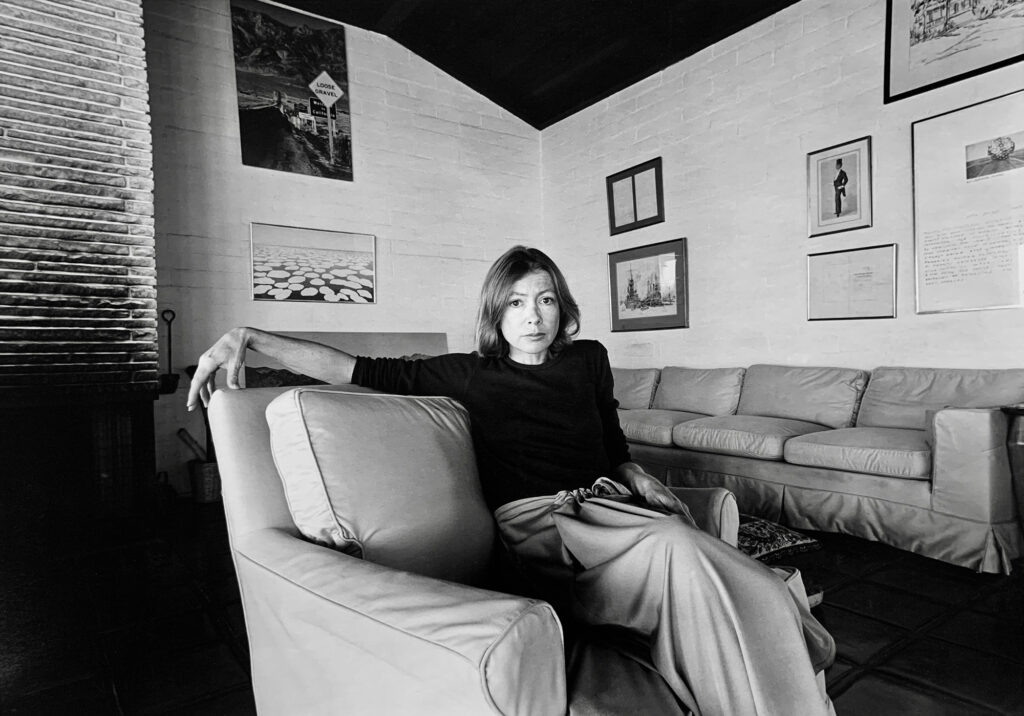

Then I discovered that among its other hidden treasures, the Harden Gatehouse was the first Los Angeles home of the late writers Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. In “The Year of Magical Thinking,” her 2005 book about the death of Dunne, Didion — a petite woman — describes pushing the heavy portal open as her husband waits on the two-lane road outside. From 1964 to 1966, this outpost of the storied Vanderlip PV estate was a site of not just ocean vistas, but of intellectual industry.

“We called it the writing factory because we were all working on something and then we would gather for dinner,” the writer Calvin Trillin told me, about his stays with his friends the Didion-Dunnes (as they were dubbed) at Portuguese Bend. “And gossip, of course.”

My recent search for Joan Didion’s muse — a fortuitous assignment that resulted in the book “The World According to Joan Didion” — led me home.

My fascination with Didion’s essays, articles, novels, screenplays, dress, domiciles, and overall way of moving in and seeing the world was ignited decades ago in an undergraduate journalism course at Brown University. She was one of only two women included in our textbook, the classic “The New Journalism” anthology edited by her friend Tom Wolfe. Her literary, sociological take on a crime story — “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream” — shifted my understanding of what journalism could be. The University of California, Berkeley, graduate was not trying to figure out who done it. (She made it pretty clear early on that she believed the accused was indeed guilty of killing her husband and then burning him and the evidence in the family Volkswagen.) The columnist for the Saturday Evening Post was interested in why. Where had the golden dream of a middle-class life in the exurbs of the Golden State gone awry? To solve this puzzle, Didion wrote not just about Lucille Miller’s upbringing in Winnipeg, Manitoba, about the family’s money problems, and about the dead man’s extramarital affair; she took the reader on a ride down the desolate subdivisions of San Bernadino, sounding the names of the roadside businesses — Forty Winks Motel, Pit Stop A Go-Go, Kapu Kai Restaurant-Bar and Coffee Shop — like a roll call of broken promises.

Wolfe called this New Journalism technique “status details”: morsels of evidence that speak volumes. Whether describing the perfume a woman was wearing in a cab in El Salvador or the posture of Dunne’s body when he collapsed of cardiac arrest in their Manhattan apartment, Didion excelled at precision observation. She was a meticulous and mellifluous writer, and her work was always anchored in the concrete even when it ascended into art. Writing was a process of visualization for her. In her 1976 essay “Why I Write,” she explained that she was trying to turn mental images into words, to answer her own question: “What is going on in these pictures in my mind?”

Whether describing the perfume a woman was wearing in a cab in El Salvador or the posture of Dunne’s body when he collapsed of cardiac arrest in their Manhattan apartment, Didion excelled at precision observation.

In 2022, just a few months after Didion’s death on Dec. 23, 2021, I embarked on my own journey through the world that Joan saw. I visited many of the places that were crucial settings for her fiction and nonfiction: Sacramento, Berkeley, Manhattan, Malibu, Brentwood, Hollywood, Honolulu, Portuguese Bend. Some of these were familiar, and familial, to me, but I tried to see them with new — or rather, with Joan’s — eyes. One of the reasons I was drawn to Didion is because I, too, have multi-generational Californian roots — I come from “the Coast,” as the young journalist mocked the term used by the snobbish New York publishing establishment in her perfect 1967 essay “Goodbye to All That.” I shared that feeling of being treated as a provincial when I moved to Manhattan. I know the desert heat of the Santa Ana winds that she felt in Trancas as well as the thrill of making the transition from the Hollywood Freeway to the Harbor Freeway as you cruise into downtown Los Angeles, as her antiheroine Maria narrates in the novel “Play It As It Lays”: “Again and again she returned to an intricate stretch just south of the interchange where successful passage from the Hollywood onto the Harbor required a diagonal move across four lanes of traffic. On the afternoon she finally did it without once breaking or once losing the beat on the radio she was exhilarated, and that night slept dreamlessly.”

Another line: “Whenever I feel troubled, I think about the sea.”

Exactly, I thought, as I read this note, handwritten by Didion, tucked in the manuscripts for “Play It As It Lays” at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley. Not just the sight, but the feeling of the sun dropping into the Pacific Ocean is seared into my being.

Top (l-r): Harden House Gate; Wayfarers Chapel; Rancho Palos Verdes coastline. Bottom (l-r): Abalone Cove; Palos Verdes beach.

Scraps of paper like that are, as Didion said in the documentary “Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold,” “gold” for biographers — a “eureka” moment for me while researching this descendant of miners in the Golden State. Didion probably intended the line about the sea for Maria, but then in many ways, Maria was a stand-in for Didion; they both drove Corvette Stingrays. I can see Didion, a woman who struggled with mental and physical ailments and family tragedy, troubled, thinking about the sea. Bodies of water course through her writing and her life: She named her first novel, set in the Sacramento delta area where she was born and raised, “Run River.” Her 1984 novel “Democracy” is centered in Hawaii. She was an early chronicler of the rise of a new kind of American city on the bottom of Florida in her book “Miami.” She never lost sight of the fact that Manhattan, where she spent the last decades of her life, is an island.

Just as Didion inspired me as a young journalist years ago, I now teach the lessons of her literature to my students at Loyola Marymount University. Status details. The conversational but not narcissistic first-person voice. The steady rhythm of sentences that vary in length but never lose the beat. The precision of word choice. The relentless interrogation of received narratives. The constant lifetime of reading, the prodigious research.

Students get it. In fact, Joan, who would have turned 89 Dec. 5, remains a muse for younger generations, year after year. The lead song on the new album by the 20-year-old pop star Olivia Rodrigo is titled “All-American Bitch,” after a quote in Didion’s 1967 story “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” Andrew Bird has two songs about Didion on his 2022 album “Inside Problems.” The 2017 film “Lady Bird” by Greta Gerwig (director of “Barbie”) opens with an epigraph by Didion. Joan Didion was an astute and fearless chronicler of her times. By carefully, critically choosing the words that brought the pictures in her head to life, she created art that transcends its time.

I never did get behind the Harden Gate. But I know the rocks below well. I’ve found octopuses hiding in holes of salt water left behind by the tide. I’ve made the swim across the sea cave that Didion describes so beautifully in “The Year of Magical Thinking”: “the swell of clear water, the way it changed, the swiftness and power it gained as it narrowed through the rocks at the base of the point.”

Newly married when they moved to L.A., Didion and Dunne shared a column in The Saturday Evening Post, alternating bylines about snakes and cops, Hawaii and dry cleaners in San Pedro. They called it Points West; here, at Portuguese Bend, lies the geographical point. Now, when I drive by the Harden Gate, I think of the works that were created, or must have at least begun their assembly, in the writing factory here: “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream”; Didion’s love song to John Wayne; her New York Times story on Joan Baez, “Where the Kissing Never Stops”; Dunne’s first book, “Delano: The Story of the California Grape Strike.” I think of the peacocks that wandered the grounds and irritated John with their shrill cries, and of the serpents — Didion and Dunne hated snakes — in the garden. I think of the baby girl that Joan and John adopted and called Quintana Roo, shortly before they left Palos Verdes for the enticements of Hollywood.

And as I round the bend, I see the sea.

Didion: A Curated Reading List

I, and most of the readers I know, consider nonfiction to be Joan Didion’s forte. If you were to start with one single book of hers, you might as well start at the beginning. “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” gathers her earliest journalism and essays, including On Self-Respect, one of her self-help pieces from her first real job in New York, at Vogue. Many selections are from The Saturday Evening Post, including the title story, her immersive report on Haight-Ashbury in 1967. This is the article that provides the title for the first cut on Olivia Rodrigo’s 2023 album “Guts.” Also essential in this collection is Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” the piece that converted me to Didiondom; On Keeping a Notebook,” one of her many instructional essays for writers; Notes from a Native Daughter,” one of the earliest pieces in which she mulls her complicated relationship to California; and Goodbye to All That,” also a love-hate story about a place (New York), but one with a seeming resolution. (She moved back decades later.)

To truly understand Didion, though, you should start with “Where I Was From,” the 2003 collection of articles and speeches in which she fully lays out the evolution of her understanding of California as the dissolute end of the American empire — and says goodbye to all that.

“Sentimental Journeys”: Decades before Ken Burns and Ava Duvernay, Joan Didion investigated the legal, media, and public lynching of young men of color in a notorious sexual assault case in Central Park. Her piece for the New York Review of Books exonerated the youths and slammed New York City.

“The Year of Magical Thinking” is justifiably Didion’s most famous book. Her ability to write about the twin traumas of her husband’s death and her daughter’s serious (and eventually fatal) illness has helped probably millions of people cope with similar situations, and remains a masterpiece of economic, precise prose.

Didion’s novels all center on female heroines. They lack the clarity of her essays, but still fascinate with their experimental narratives. “Democracy” — an early example of autofiction — is probably her most fully achieved.

With John Gregory Dunne, Didion wrote and doctored many screenplays. I think their first, “Panic in Needle Park,” was their best.

In the title piece of the second collection of her essays, “The White Album,” Didion digs deep into autobiography in order to tell an episodic story of L.A. in the 1960s. Also essential in this collection: “Georgia O’Keeffe” and “Quiet Days in Malibu.”—Evelyn McDonnell

Evelyn McDonnell, a frequent contributor to LMU Magazine, is a professor of journalism in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. She has written or coedited eight books, including “Queens of Noise: The Real Story of the Runaways.” McDonnell’s latest book is “The World According to Joan Didion.” Her article titled “Cougar Town,” about cougars in Los Angeles County and a proposed wildlife crossing over the 101 freeway, appeared in the summer 2021 (Vol. 10, No. 1) issue of LMU Magazine. Follow her @EvelynMcDonnell.