With his deeply burnished skin of dark mahogany, coiled short ringlets of hair that frame his face like a spiky crown, and courtly manners, Jok Madut Jok is most assuredly a child of Africa. The 45-year-old LMU history professor is tall and imposing, with the powerful build of a linebacker that is barely contained by his crisp, white shirt, charcoal-colored slacks and tightly knotted gray tie. Considered one of his country’s “leading intellectuals,” Jok has been at the forefront of efforts to transform South Sudan, the world’s newest state, into a genuine nation with a collective identity and sense of purpose. The latest events unfolding in his embattled African country are never far from his thoughts.

This past December, when he traveled to his homeland for the holidays, Jok suddenly found himself in the midst of a war zone. A power struggle between two political rivals erupted into violence the day after he arrived. He spent the next several weeks visiting U.N. refugee camps outside of Juba, the nation’s capital, and distributing donated food to many of the more than 20,000 people who had sought shelter and were stranded in the camps.

The latest round of bloodshed fills him with anguish. “This went from a struggle for power to being an ethnic-based confrontation, which is what is making it so deadly,” Jok says. “We’re talking about a million people displaced and 10,000 people dead, about mothers and children sleeping in extremely congested quarters, in flooded camps as the rainy season sets in, about deadly diarrhea outbreaks, or getting malaria or typhoid, and dying.”

Jok returned to the United States in January 2014, as the spring semester began at LMU. While he leads something of a schizophrenic existence, his feet seem somehow firmly planted on two continents. Trained as an anthropologist at UCLA, where he received his Ph.D., he considers himself a student of history and human behavior, and is intrigued by deciphering what makes human beings behave the way they do. A high-profile academic who has spent most of his adult life teaching at LMU, Jok has done stints at think tanks in places like Washington, D.C., and taught at Oxford University, and he’s written three scholarly books and numerous articles about gender, sexuality and reproductive health, war and slavery, and gender-based violence.

But Jok’s connection to South Sudan runs deep. He spends long summers in the African savannah of his homeland, an oil-rich country about the size of Texas, with rutted roads and poor villages that lack basic services, and also in the nation’s more modern capital, Juba, a river port on the banks of the White Nile with a population of nearly 400,000 mostly native Sudanese.

Growing up with his extended family of 17 siblings and half-siblings on the grassy plains in the northern regions of South Sudan gave him a firm foundation, Jok says. He still misses the warm embrace of his native village and what he calls “the fabric of society, the social relations where everyone knows everyone one else, where everyone is somehow related, and you don’t need police or a judge or structures of governance because the social fabric takes care of things. Your face — your integrity, your sense of self-esteem and the respect that people give you — is more valuable than any material goods. Your behavior has repercussions, not just for you but for your entire family.”

A country doesn’t come with a user’s manual, so we have to create not just the structures of the state but also build a nation — which is about people — so that this entity called ‘South Sudan’ is something that they have a stake in.

His parents’ influence was the most formative and set him on his life’s path. His farmer father was a great believer in education, which motivated him to go far beyond his small village and into the world — he received a government scholarship to study in Egypt after finishing high school and was then awarded a Ford Foundation scholarship to attend UCLA.

“My father had foresight and a dedication to the idea that the measure of a man is how he sees himself in other people’s positions,” recalls Jok. In 2007, Jok founded a primary and secondary school, the Marol Academy, in his hometown of Marol; 653 students are currently enrolled, 80 of whom are now in high school. Jok hopes they’ll follow in his footsteps by attending university and taking their place as his troubled homeland’s next generation of leaders.

But it was his mother who made the most enduring impression on the young Jok. With no daughters, she had to do everything by herself, and Jok was the only child who worked with her doing domestic chores, following her when going to the market, milking cows, retrieving water from the well, digging up the land in the fields or pounding grain for meals. “That is where I began to be curious about why it has to be like that, and why women do everything,” says Jok, who has written extensively about the plight of women in Africa. “Even my father chastised her for turning me into a girl. But she said, ‘Nonsense, you are a better man for knowing how to do women’s work.’ ”

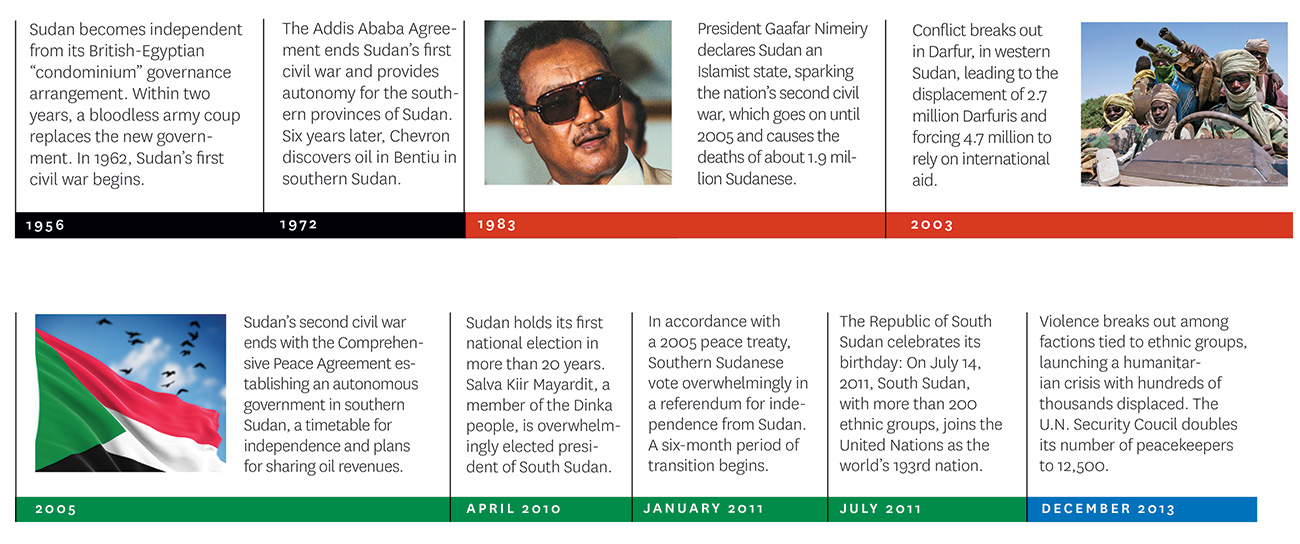

Still, despite a stable upbringing, Jok grew up in a country torn by conflict dating back more than 50 years, when longstanding religious and tribal divisions between the north and south of Sudan spilled over into violence as the country prepared to gain independence from joint British and Egyptian colonial rule. Southerners in Sudan, who mostly followed traditional African and Christian religions, worried that authorities in Khartoum, the capital, would adopt an Arabic and Islamic identity for the nation. A group of southern army soldiers mutinied in 1955, triggering a civil war between the south and the Sudanese government. Although a cease fire was engineered in 1972, hostilities erupted again in 1983, sparking 22 years of guerrilla warfare that claimed at least 1.5 million lives and displaced 4 million more, before the conflict ended in 2005.

In July 2011, amid great fanfare and jubilation, South Sudan became a sovereign nation. The country’s birth was celebrated by close to 200,000 people, 31 heads of state and government delegations from around the world.

“Before independence, Sudan was home to Darfur, where genocide has been committed, and the Nuba Mountains, where people are being exterminated, not to speak of the genocide in South Sudan itself during the war when Khartoum was launching aircraft missiles into communities, blowing up homes, maiming livestock and destroying crops,” Jok says. “Because of independence, we thought we had left all of that behind us.”

Jok took a yearlong leave of absence from LMU to help build the new nation. He was appointed undersecretary for culture and heritage in the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports by President Salva Kiir Mayardit. To unify South Sudan’s more than 70 ethnic groups into a real nation, Jok helped establish structures and customs, both large and small, ranging from symbols like flags, a national anthem, currency and postal stamps, to major projects such as developing national archives, a national library, educational services and cultural centers.

“A country doesn’t come with a user’s manual, so we have to create not just the structures of the state but also build a nation — which is about people — so that this entity called ‘South Sudan’ is something that they have a stake in, something that will give people a sense that they are citizens in the nation and not just their tribe,” he says. “I worked on creating the national archives because the history, the struggle, the journey to become independent needs to be documented and put someplace where everybody sees themselves represented in that story. I also worked on creating a cultural park with a museum, a theater and a culture center. All of these are ‘houses’ that allow our Sudanese to dream as one people. They translate the euphoria of independence into real things in one’s life and facilitate that sense of collective identity.”

Although disheartened by his nation’s ongoing struggles and outbursts of violence, Jok remains optimistic. “We’ve been here before, and we managed to rise above it, and this too shall pass,” says Jok, who is working on a book about his homeland and plans to return this summer. “But my heart still bleeds for every South Sudanese who dies senselessly, for every human being who dies when it is unnecessary.”