An expatriate reflects on the language of politics back home.

In my late 20s, I fell in love with a Canadian and moved to another country — something life-altering that was both safe and slightly exotic. Canada, exotic? I’d never met a Gordon before (my husband). And when I arrived in Toronto, I thought, “Why hasn’t anyone discovered this place yet? It’s modern! It’s sophisticated!” The safe thing was, I was still in North America, and everyone spoke English. I thought I’d fit right in.

Living in Canada, I’ve pretty much missed the family births, baptisms, first communion, graduations, golf trophies and swim medals. I can only try from a distance to keep open a conversation that links my family and me across the miles.

With this regret also came blessings: another country to know, another people to understand and another way to think and behave. Yet it wasn’t until the 16th of October, 2002, after living in Canada for about 25 years, that I finally gathered with immigrants from more than 30 countries to say “Je suis Canadien.” Although I would never give up my U.S. citizenship and although I feel pride and sorrow in the fluctuations of my birth country’s destiny, I am finally a citizen of Canada, too, because I live here.

I now have daily access to a collective consciousness that has been shaped by a different tradition. The Canadian national anthem, for example, a mere 63 words, has no reference to war. Although Canadians have acted pivotally and bravely in wars alongside their U.S. counterparts, their national identity is connected to strength, freedom and glowing hearts. Canada has never been the greatest country in the world to anyone but Canadians, not because they believe Canada to be greater than others, but because it’s home. Living next door to the biggest guy on the block has developed in Canadians over time a first response to conflict, which — anywhere but in the hockey rink — is to listen.

Over the years, I have learned much from my Canadian peers. I’ve seen the long-term effects of respectfully stating my opinion while acknowledging the right of another to disagree. As I saw that posture work positively, I gained confidence in watching and listening — and deferring.

So I was troubled when I began to realize that rational public discourse in the United States has more or less fallen apart. I first noticed it on the car radio during a road trip. I could hardly believe what people were saying to each other — in public. What initially astonished me was how many self-proclaimed Christians participated in these verbal free-for-alls, hurling insults and standing behind mean-spirited politics that seem to me utterly devoid of Christian charity.

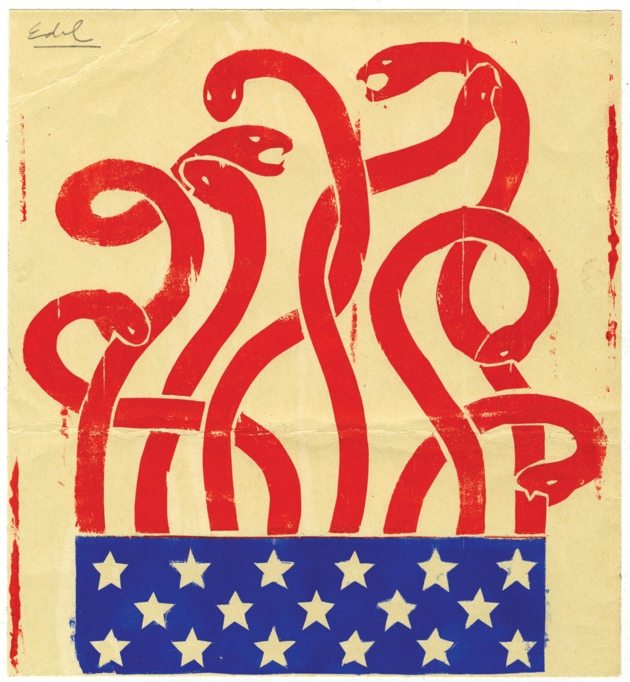

It’s now the United States of Us vs. Them, where people exercise their Second Amendment right by bringing guns to public meetings — to intimidate — or is it to shoot someone who disagrees? Now it’s difficult to converse about anything deeper than the weather. Discussion about money and politics used to be politely avoided out of privacy, but now my friends and family must know: What side am I on? In a little more than 20 years, a climate of hatred has become the status quo.

How can you put a Pandora like that back in the box? From a distance, there seems to be a vacuum of respect, an excess of ideology, a pollution of negativity. Yet each one of us Americans deserves respect. Regardless of whether or not we’re right. Or left. The lifeblood of a true democracy is free speech, the double-edged sword that must be handled with care. And kept sharp with respect.

Caitlin Hicks is a writer, playwright and performer who lives in Robert’s Creek, British Columbia, Canada. She welcomes rational discourse and can be reached at www.caitlinhicks.com.

.