He works with original manuscripts that were hand-copied on parchment more than a century before Columbus discovered the New World. They are hard to read. To make out words, Shepherd often must focus on a single letter at a time. The poem runs about 170 pages.

Such care is one reason Shepherd has emerged as one of the world’s top scholars of medieval literature. His job is to translate and interpret Middle English texts that few of us could understand in the original.

“Piers Plowman” offers a classic telling of the quest for salvation in a world of temptation and sin. It is also an eye-opening look at events of the 14th century that helped to shape our modern world. They include the Black Death, which killed at least a third and perhaps half of Europe’s population; the beginning of the end of the feudal economy that tied serfs to the land; and the rising discontent against the Catholic Church that led to the Reformation in the next century.

Fortunately, we are able to read the poem in translations such as the Norton Critical Edition, which Shepherd co-edited. It includes the first side-by-side versions of the poem, one in medieval English, one in its modern translation. It enables untrained readers to delve into the poem without stumbling over almost every word. Those who take the plunge may be surprised at the result. “It has a pull even on the modern reader,” says Shepherd. “I don’t know anybody who has studied the poem who didn’t come away saying, ‘I want to be a better person.’”

Part of the poem’s power stems from author William Langland’s graphic approach. One of his more loathsome characters, a lout named Glutton, is on his way to church when he happens upon a bar. Soon he’s inside swilling ale and stuffing down food while passing so much gas that other patrons hold their noses to shut out the stench. When he finally attempts to leave, Glutton stumbles and falls, then vomits custard in the lap of the patron who tries to help him up.

Of course, modern humans often behave no better, and it’s easy to see our own moral failures in Langland’s characters — a cast that also includes a thief, a prostitute and a wayward priest. “I’ve spoken to people who run missions and soup kitchens,” says Shepherd. “It’s surprising how much overlap there is in the way they see the world and the way Langland saw the world. If Langland were dropped into L.A. today, the minute he saw it, he would know exactly what he was looking at.”

Scholar as Sleuth

Translating the poem correctly is quite a job. “Piers Plowman” predated the printing press, so all copies were handwritten by scribes who inadvertently introduced errors, put their own spin on the poem, or changed spellings at a whim. To top it off, author Langland wrote three editions of his masterpiece. Fifty-five copies of the book survive, all of them different. Shepherd’s job is to comb through multiple editions to determine which words and thoughts were the author’s and which came from the scribes. “It’s very difficult at times to know what was Langland’s and what wasn’t,” Shepherd says.

Sorting things out requires a blend of scholarship and finely honed investigative skills. “Stephen is a scholar of extraordinary breadth and depth, whose wit and uncanny sense for investigative literary sleuthing permeates all his work,” says Theresia de Vroom, Shepherd’s English Department colleague and director of LMU’s Marymount Institute for Faith, Culture and the Arts.

Shepherd also draws praise from Oxford Emeritus Professor Ralph Hanna, one of the world’s authorities on medieval literature, for his work on the Norton CriticalEdition. “It’s an extraordinary piece of work in which Stephen, with no fanfare whatsoever, completely re-examined the text.”

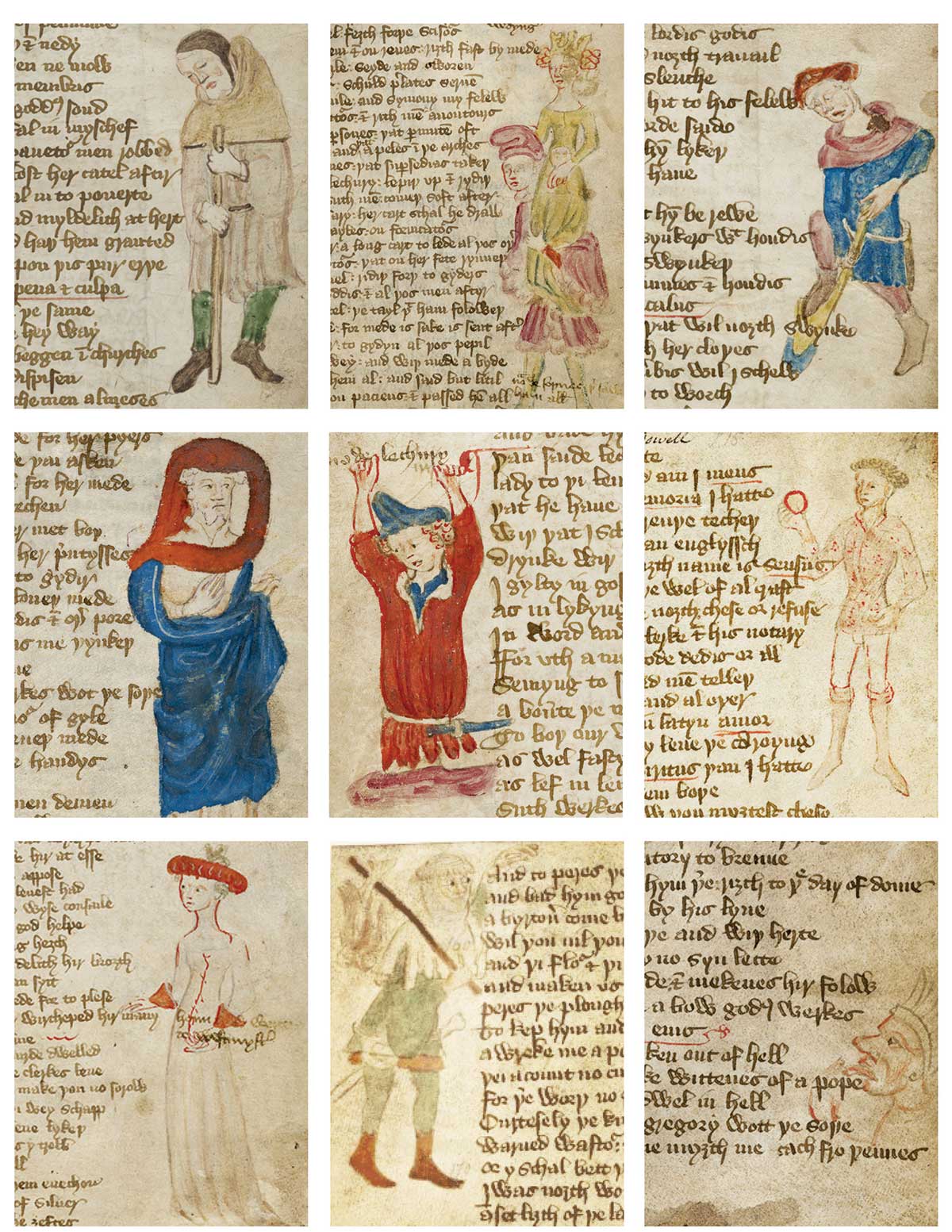

Lately, Shepherd has applied his skills to an unusual version of the poem, which contains 72 illustrations in the margins. They apparently were inserted by an Irish intellectual who also served as scribe for the copy. Since many of the illustrations bear no obvious relationship to the text, scholars have long tried to figure out their purpose and meaning. Some have speculated that the drawings offer critical remarks about Langland’s text. Shepherd doesn’t think so.

“The new idea is that the illustrations link ‘Piers Plowman’ to other literature that was read at the time, and vice versa,” says Shepherd. “The illustrations provide an opportunity to go beyond speculation about what books a typical reader of the time would have known and had access to.

“I expect the illustrator would have had a very well-off patron — someone like a bishop — who paid him to do them. The patron would then attempt to guess what books the illustrations alluded to.”

A Medievalist at Home in L.A.

Now Shepherd is trying to do the same, drawing on his extensive knowledge of medieval literature. The task requires an immense amount of research. So far, Shepherd thinks he has come up with the literary sources for 10 of the 72 illustrations. For instance, one illustration shows the Roman Emperor Trajan. As a pagan, Trajan would hardly be the stuff of Christian literature. But Dante included Trajan in his “Divine Comedy,” which was published more than a century before “Piers Plowman.” Another illustration, which shows a digger with his shovel, may have taken its inspiration from the Bible.

Shepherd’s interest in books began in childhood. After living in Africa and Great Britain, Shepherd’s family settled in Peterborough, Ontario, when he was 6. The city was mad about hockey, but Shepherd already was too old to take up the game in a country where youngsters pull on skates not long after learning to walk.

At his father’s suggestion, Shepherd turned to computers and technology — skills he later would use to analyze ancient manuscripts. He also gravitated toward English literature and English archeology. After earning his Ph.D. from Oxford, where he learned to read and interpret medieval texts, Shepherd spent 17 years in Dallas at Southern Methodist University.

Two things brought him to Los Angeles. In 1995, Shepherd attended a summer seminar that dealt in part with “Piers Plowman.” By the time the seminar ended, he was hooked. He also knew the famed Huntington Library, located in nearby San Marino, Calif., had four copies of the book, all of unique interest. The Huntington’s is the largest collection of “Piers Plowman” originals outside of Britain.

When he finished the seminar, Shepherd knew he needed to live near the Huntington, but it took 11 years to land a job in L.A. In 2006, he got his break. LMU was seeking a professor with an interest in medieval literature. “It was the right time, the right place,” Shepherd says.

This year, LMU’s Marymount Institute Press published “Yee? Baw For Bokes,” a major collection of essays on medieval manuscripts, which Shepherd co-edited. The book, which was peer-reviewed by leading scholars before publication, contains his groundbreaking essay on the illustrated “Piers Plowman” manuscript, which resides in Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

Reading ancient manuscripts requires a detective’s skill of uncovering facts, a bit of high-tech wizardry and a lot of patience. The manuscripts are marred by blurs, erasures and spots where wet ink from one page bled onto the opposite page. The writing in hand-scribed texts is often cramped and hard to read, and doesn’t necessarily show up well in digital form or photocopies. For these reasons, scholars prefer to look at the originals, often traveling long distances to see them. “There are things in a manuscript that technology can’t reproduce, and you simply have to look at the original,” says Shepherd. “Where every word counts, it’s important to see words correctly.”

But after more than six centuries, some details of the text have faded, leaving them invisible to the naked eye. Here Shepherd’s computer skills give him an edge. “The quality of digital imaging is so high that you can manipulate it to see things that aren’t visible or discernible in the original,” he says. To do this, Shepherd pops an electronic facsimile on his computer screen, then shades it with simulated infrared or ultraviolet light using an Adobe Photoshop program. “It brings out things that aren’t visible to the eye in the original,” he says. “You can also superimpose one page on another to see if wet ink from the opposite page left an impression that would leave an incorrect image.”

Though he has worked with medieval texts for decades, Shepherd is still captivated by the work. “Once you’ve learned the handwriting and vocabulary, they start to speak to you in a way that brings back once-living hands and minds. When one discovers something new, it’s both exhilarating and a little intimidating, like archeologist Howard Carter opening King Tut’s tomb.

“Medieval manuscripts typically have a look, feel and even a smell like no other book. You know you are in a different place and time the moment you open one.”