I was on a critical mission: My Norton Anthology of English Literature, Vol. 1 (Fourth Edition), would be hard to miss, even in my jumbled shelves. A green brick, three-inches thick, with its gold-leaf-embossed cover and spine, had traveled vast expanses with me. It was the anchor of my early-adult book collection, both talisman and companion. I lugged it across the city, the county and the state long after I’d graduated from the little school on the bluff — LMU. I’d annotated it in pencil and ballpoint, its near-onion-skin pages wrinkled and folded in places where I’d shut it too quickly, mindlessly. In other words, I lived within it.

Over the years, I marked my favorite poems, plays or novel excerpts with repurposed scraps for bookmarks: remnants of old Christmas wrapping paper; hastily scratched epiphanies on college-ruled loose-leaf; lavender rose petals pressed in wax paper from a graduation bouquet my parents had given me. Each of them, stories within themselves.

So, how could it have gone missing?

All along, I’d been taking English courses as if I knew I needed an emotional safety net.

I inspected and retraced. With each circuit, my fear rose: It wasn’t on the shelf where it should be, this extension of myself.

To calm my mind, I self-counseled: No one, absolutely no one, would come into your home to nick a 40-year-old book with a broken spine from your chaotic shelves. No one.

A mystery or a tragedy? Only time would tell.

As a commuter student, I’d hauled that book (and, later, Volume 2) across campus daily. It was so heavy that I would sometimes carry it outside of my backpack, so as not to strain my lower back. Occasionally, I would pause to converse with friends, balancing it on my head, freeing my hands to make change for before-class coffee. And for many years, as I moved from dorm to flat to sublet to apartment to home I could call my own, every time I set up my bookcase I slid those volumes onto my shelves, along with a slender collection of Shakespeare’s sonnets (a Pelican edition), T.S. Eliot’s “Selected Poems,” a Penguin Classics edition of John Donne’s complete works as well as a glossary of literary terms. All of them: Books that were holdovers — essential tangible evidence — from my years as an English major.

I’d entered LMU “undeclared,” with quick-sketch ideas about studying Communication Arts — maybe I’d find a path to journalism or working in radio, it sounded practical-ish, I told myself, if pressed. For as long as I can remember, I loved books and reading. As soon as I could, I began to try my hand at something edging toward writing, attempting to re-create worlds — mimicking my favorite stories, trying to tease the scenarios out just a little bit longer. Yet, while I loved reading and writing, of the path that it might lead to I was not certain.

Months in, I officially declared myself “C.A. major,” with a writing emphasis, and enrolled in the required, foundational classes: “Art of the Cinema” (which I loved, and learned to “read” and critique movies like books), an entry-level screenwriting class (which challenged me) and my first production class, focused on television (which, in all honesty, broke me). All along, I’d been taking English courses as if I knew I needed an emotional safety net. I adored my freshman composition class with Sharon Locy and signed up for all of the required courses, salting in electives, parallel to my communications courses.

But it was my English literature survey class that creaked open a trapdoor inside me. We read “Beowulf” and “Le Morte D’Arthur” and “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.” (I’d come to LMU already with an obsession with Arthurian legend, from children’s stories, so these readings pushed me, happily, through new mazes and boggy stretches.) We read John Donne, Gerard Manley Hopkins and W.B. Yeats. It wasn’t that I ever needed permission to read, or that I hadn’t been exposed to a range of authors. I grew up in a home headed by two educators, the house a forest of books branching out into diverse genres. At home, I’d read F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and Ray Bradbury from the school-bound volumes my mother taught from, as well as James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks and Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, from copies that were from her personal library.

But in that sun-drenched classroom, I was invigorated by this more formal pursuit, due, namely, to the zeal of particular professors who encouraged our blooming ideas about imagery, intent, antagonists and assonance. Even for someone, who at that point seldom spoke up in class, I found it became a ritual that I welcomed.

I touched the spines of those books that meant so very much to me as a young person trying to find her voice and her way.

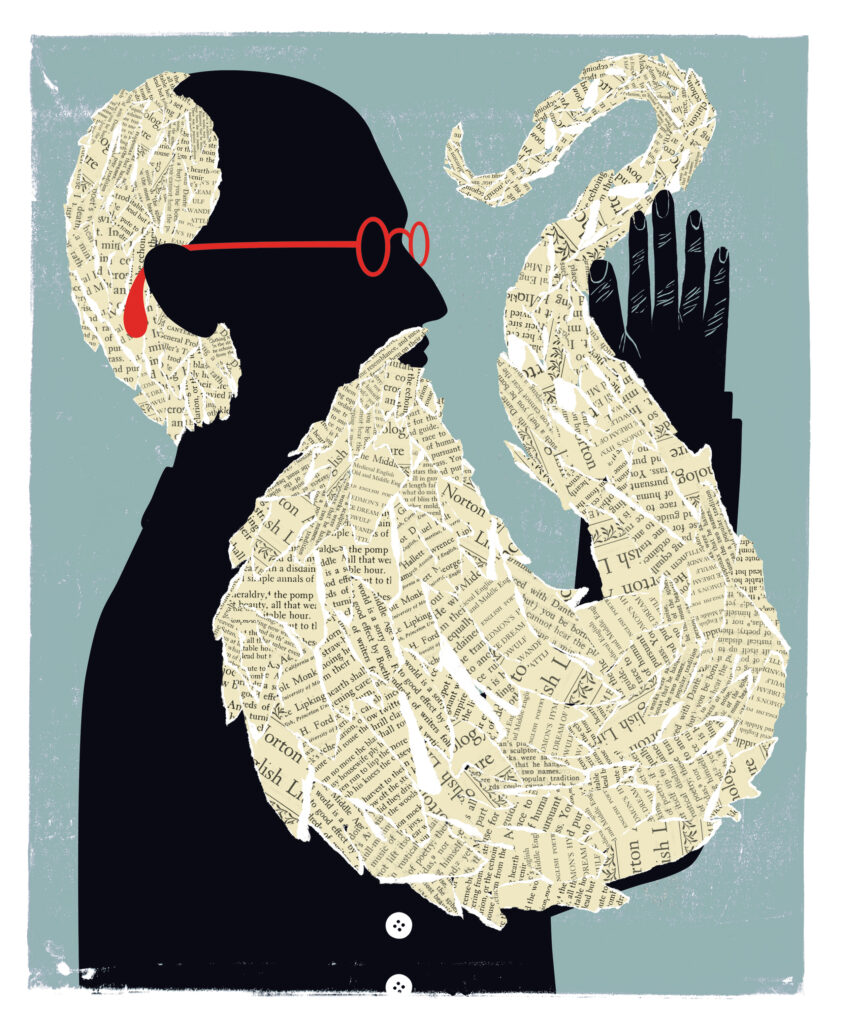

Reflecting on that time — and that weighty Norton — I can’t not think about my survey professor, Ted Erlandson — his white column of beard that trailed, whimsically, (and Merlin-like) down to his chest, and the ringing joy in his voice as we read aloud in class and untangled our thoughts about what we’d just absorbed. In his class, we were, of course, expected to memorize and recite in Middle English the first 18 lines of the general prologue of “The Canterbury Tales.” The proposition was met with moans and required many visits to the library audio lab to listen to tapes, because not only would we need to nail the lines, but they also had to be pronounced correctly, with the precise stresses, twists and trills. I clearly remember him trying to coax the reluctant with the promise that one day, deep into our future, we would be able to impress someone at a cocktail party. At least draw them into a conversation: “Mark my words!” (Indeed, it happened; he was prescient! Another story for another day.)

I didn’t fight it, actually. Not because of some impulse to please, but because I genuinely enjoyed listening and following along to those strange beats and pauses, it took me down a path into something vast. I loved the music.

Some afternoons, I’d pass by Dr. Erlandson on the quad, where he would greet me with expansive enthusiasm, “How is My English Scholar, today?”

I had been knighted, reborn.

In those same years, I’d landed a part-time job working evenings and weekends as a bookstore clerk, and when the semester was through and I wasn’t reading for assignments, I would construct my own summer syllabus. Shelving books meant interacting with them in a different way, looking at covers, spines and jacket copy. In this way, in this intimacy, I learned about new authors and genres. Often the adjacencies — that beauty of browsing — led to serendipitous discoveries: The first Jack Kerouac I would (finally) read cover to cover (“The Subterraneans”); the urgent and splintery short stories of Leonard Michaels (“Going Places” and “I Would Have Saved Them If I Could”); the elegant architecture of Gina Berriault’s novellas and stories (“The Lights of Earth,” “The Infinite Passion of Expectation”); the heart-rending clarity of Lucille Clifton’s poetry (“An Ordinary Woman”); the stylish story sequences of Andrea Lee’s fictional post-Civil Rights era Black family matters (“Sarah Phillips”). These became books I lived not just with, but in. They came home to take up residence on my rapidly filling shelves.

Visiting a friend in San Francisco the summer before I moved there for graduate school, I’d packed along a copy of James Baldwin’s “Giovanni’s Room,” which I’d purchased from our bookstore and had been, for some reason, saving. I devoured most of it in one sitting, finishing it in a bathtub, letting the water go from steaming to tepid. This reading was the one that shifted something in me, the one that sent me back to his nonfiction. I raided my mother’s shelves of her first-edition copies of “The Fire Next Time” and “Notes of a Native Son.” I was finding not just a voice, but an intention: a way to write concretely about conundrums and abstractions. Incidents and life-collisions that left my stomach in knots, and me, I thought, without words. Baldwin’s curiosity and rhetorical strategies lit a path: I began to engage the subjects that mattered to me — or that confused or delighted me — in a voice that was finally becoming not just “recognizable” but mine.

Much of this — the specific influences and imprints; these ways with words and ways of being on the page — I’d yet to put together, until the pandemic’s forced pause, when I happened upon a fascinating biography of Louise Fitzhugh, who wrote and illustrated one of the most important books of my childhood, “Harriet the Spy.” In the biography “Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Renegade Author of Harriet the Spy,” the author Leslie Brody makes note of how Fitzhugh’s 11-year-old protagonist, Harriet M. Welsch, launched many a child toward pathways — even careers — that involved looking, absorbing, and questioning, and recording it all onto the pages of a notebook. Harriet’s “snoopiness” was, on the face of it, “curiosity.” But it was also about power: about sussing out what is hidden, for better and often for worse. There was a price for being bold, for naming what you saw.

Some afternoons, I’d pass by Dr. Erlandson on the quad, where he would greet me with expansive enthusiasm, “How is My English Scholar, today?” I had been knighted, reborn.

Finishing Brody’s book, I went back to those old shelves of old selves, looking first for Harriet, then trying to retrace a trail. As crazy as it sounds, I had tried to keep every formative book I had read. As a full-time journalist, I hadn’t really taken the time to look back, I’d just kept accumulating, moving forward. I touched the spines of those books that meant so very much to me as a young person trying to find her voice and her way. It was like a reconvening of old friends: I marveled at my own shelves’ adjacencies: Fitzhugh and Fitzgerald. Baldwin and Berriault, Morrison and Michaels, Joan Didion and the other Donne, and more. I started to make short stacks, put myself on a journey: Here were the books I had read to understand structure, others I read to understand more about risk-taking, the others that taught me how to train my ear for music, the others that taught me rigor, and the ones that still demanded my focus and patience. When I page through my tattered “Giovanni’s Room,” I feel the chill of the cold water, the baptism. With Michaels, it was a breaking through, blowing up the page, then playing with the shards. With Morrison, it was the elevation of our voices, Black voices, and sacred back-porch spaces and the specific intricate ways we wound through stories. Wading back to these books reminded me what I was reaching for: They helped me not just find my voice, but to raise it. They told me a lot about the road I’d been on and pointed to others — books I’d saved for the right moment — I still had yet to travel, the shades of the person whom I might still become.

Now I know: I have lived to understand that, indeed, the journey is as open as your questions, as the risks and chances you are willing to take. Literature teaches you just this, all along the way.

Why I had held on to that book, I knew, had something to do with time travel, being able to periodically wander back and trace old pathways. Those journeys weren’t simply about re-reading the printed text; I also relished in revisiting my old notations, seeing my early thoughts emerge on the page, in the volume where I had very first encountered the work, first entered into conversation with it: I sometimes wanted to sit with that person again.

My best guess is that my Norton didn’t survive my last move. Or perhaps, was the victim of a particularly stringent act of pandemic culling, to make room for the new. The mystery may not be a tragedy, just a necessary act of moving forward. But in this year of revisiting, of reconsidering the ride and feel of comforting touchstones, I’m now realizing that I didn’t need the very specimen. I could still access those old selves, those old sensations.

I’d absorbed plenty — the sonnets, the soliloquies, the tragedies, the odes, polemics and manifestos. While those books on the shelves are powerful, still, the ones that have gotten away, have moved on to other homes or into other hands are now part of someone else’s story, providing either foundation or filigree. I didn’t need to physically carry them any longer; in truth, I already was: They were there, every day — committed to memory.

Lynell George ’84 is a journalist and essayist based in Los Angeles. She is the author of “A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia E. Butler.” Her essay titled “Sweet Hope” (LMU Magazine, Summer 2018) was named among the Notable Essays and Literary Nonfiction of 2018 in “The Best American Essays 2019.” Lynell George earned her bachelor’s degree in English in the LMU Bellarmine College of Liberal Arts. Follow her @LynellGeorge.