Technological change is reshaping how music is heard — CD players and iPods are no longer necessary, never mind cassette players or turntables — and how it is made, engineered and distributed. We asked a rock guitarist, a KCRW deejay, a journalist at Billboard magazine, a sound engineer and a professor who composes film music to describe the change they see, and adapt to, every day.—The Editor

Maybe it’s nothing new. Every generation has looked back and lamented things that have disappeared or changed in ways that seem discouraging. But the pace of change in the 21st century, especially in the world of popular music, has been so rapid that it’s easy to overlook how different things were not so long ago.

At the century’s turn, cities were still filled with record stores, fans were primarily buying recordings as physical objects, record labels were well staffed, newspapers and weeklies employed music critics, radio stations and clubs were mostly independently owned, and despite decades of ups and downs, music industry revenues had hit a new peak. There’s never been a perfectly stable landscape or music-industry utopia — and labels sometimes exploited musicians. But there was a structure that savvy musicians, deejays, journalists, producers and record-store clerks could navigate. Revenues for recorded music in the United States — from cassettes, CDs, videos and other sources — peaked in 1999 at $71 billion and have fallen nearly every year since.

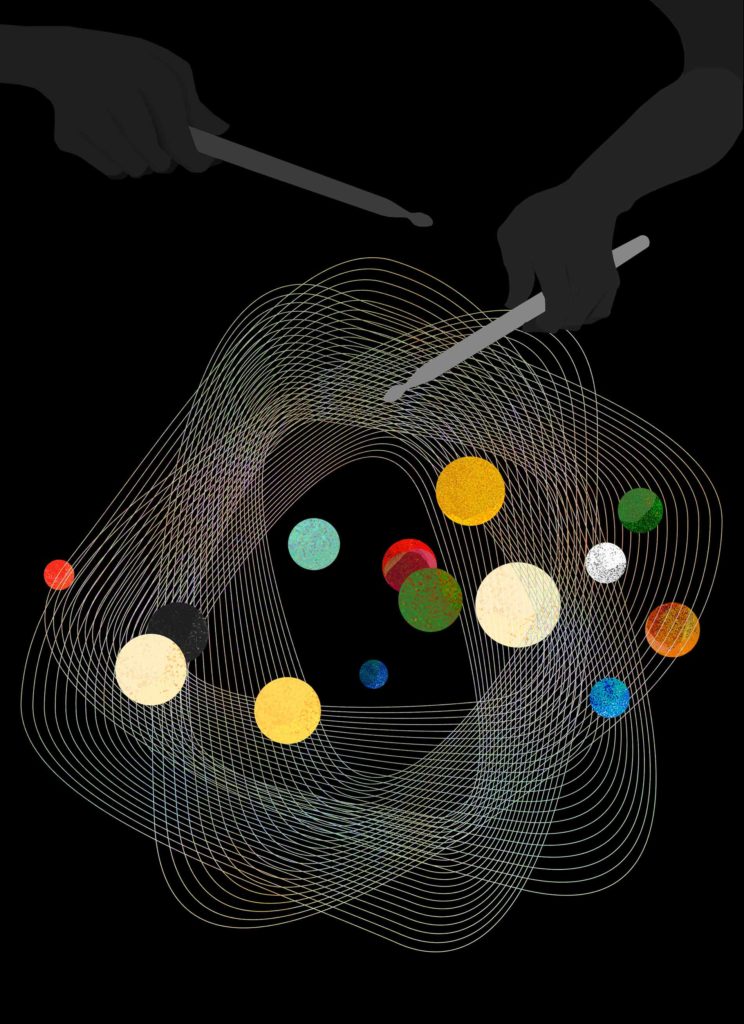

The speed and depth of change has been so intense that it can be difficult even for people enjoying the ride to figure out what’s going on. One thing most observers can agree on is that the making and selling of music has been radically redrawn by digital technology, changing habits and a new economy bent on disintermediation — cutting out the people and steps between creators and consumers.

“Basically what happened is that music got democratized, both in terms of its production and its distribution,” says Mladen Milicevic, an experimental-music composer who chairs the Recording Arts Program in the School of Film and Television. No longer does a musician need a supporting cast — engineer, producer, publicist, label rep and so on. Even musical training has become optional. “Before, you needed skills to play music — you needed to know an instrument. Now, you can build electronic loops or something.” In some ways, he says, this is progress. “And everybody’s doing it — you have millions of people making music and putting it out there.” It’s not only easier to make and disseminate music, it’s far easier for consumers — anyone with an Internet hookup — to find it.

Jason Bentley ’92, music director at KCRW and a onetime general manager at KXLU, has been working as a deejay since the late ’80s. “I am old enough to remember trucking around crates of records to clubs all over the world,” he says. Bentley still deejays at clubs and festivals, but these days he uses a tiny flash drive. “So I can have a world of music in my pocket.”

For some people, then, things have certainly gotten easier. But whatever the bright spots, the recent damage is hard to shrug off. Despite new “revenue streams” like digital downloads and services like Spotify, and high ticket prices for blockbuster never-say-die bands like the Rolling Stones and U2, the music industry’s revenues are way down. Pharrell Williams’ song “Happy” was hard to escape for about a year. But the 43 million Pandora plays it got internationally earned Williams about $25,000. The vast majority of rock, pop and R&B musicians are netting far less. Specialized musical forms such as jazz, acoustic blues and classical music, have fared even worse.

Despite new “revenue streams” like digital downloads and services like Spotify, and high ticket prices for blockbuster never-say-die bands like the Rolling Stones and U2, the music industry’s revenues are way down.

Another tangible decline is in record stores. Greater Los Angeles alone has lost, in recent years, Rhino Records, the Licorice Pizza chain, Aron’s, Virgin Records, Tower Sunset and Tower Classical, and others. Gail Mitchell ’75, senior editor at Billboard magazine, recalls a now-defunct chain that served black L.A. “I hate the record stores going away,” she says. “When I heard about new acts, it was because I had a favorite record store [VIP in the Crenshaw District] and a guy there who knew what I liked.”

Dusk Bennett ’98, a sound engineer, producer and SFTV lecturer, enjoys a lot of things about digital technology. But soon after establishing his own recording studio after graduating from LMU, he saw a “perfect storm of technology” redraw not only his field but the very way musicians approached their craft. “More and more I found that musicians were relying on the engineers to get their performances,” he says. “I especially saw it on vocals: ‘Auto-tune will fix it for us.’ Musicians stopped taking pride in their performances. So you find yourself becoming a musical janitor, cleaning up their [messes]. Or they say, ‘I can record it all at home.’ In both situations, the product suffers.”

Some bands and solo musicians have been genuinely liberated by the decline of record labels and the larger infrastructure. It certainly means a musician has fewer people to pay. But Mitchell says many of the soul and R&B musicians she most admires — Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Prince — would have a much tougher ride today. Some of them had to stand up to their labels in order to pursue their artistry, but all benefited from A&R people who recruited them and supported their careers at vulnerable early stages. “If they started doing in today’s world what they did in the ’60s and ’70s,” she says, “I don’t know if they’d be able to break through. … Today, labels have no patience for evolution.”

It may be, though, that the trouble in the music world is part of a larger cultural or even psychological crisis.

Don’t blame the Internet, says Eric Erlandson ’86, guitarist and co-founder of the band Hole. He sees a larger loss of bearings that goes back to a culture of narcissism in the 1970s and celebrity-and-money worship in the ’80s. Technology has pushed us beyond all that, and it’s become harder not only to make a living but to find the peace of mind to create in music. It’s not just technology, but the whole velocity of contemporary life. Erlandson calls today’s sensory overload the age of “overwhelm.”

The majority of music consumers are young people, and, says Milicevic, they have more distractions — social networks, video games, endless television channels that feed to cellphones. “My students today have access to more music than they could ever listen to,” he says. “So they listen to only 30 seconds of a song, and it needs to be instantly catchy or they move on to something else. There’s software that jumps to the chorus of the song.”

And who decides which songs move into the hit parade? Increasingly, this will not involve human beings. One of Milicevic’s former students is working with Rihanna, who has received rough recordings of about 80 songs and will record about a dozen of them for her next album. Guess who gets to choose those songs? Well, “who” is not really the right term. Software now reads the patterns in songs and compares their melodies, rhythms, timbres and so on to previous hit songs. “Somebody has to go through those 80 songs,” says Milicevic, “and I guarantee you it is not going to be a person.”

Given predictions that sound dystopian, and certain trends that are likely to get worse, some see ways to ride these new waves.

Bentley points to the way new music — some of it genuinely adventurous — shows up in movies and television shows, through licensing, much more than it did a decade or two ago.

“I hate the record stores going away,” Gail Mitchell says. “When I heard about new acts, it was because I had a favorite record store [VIP in the Crenshaw District] and a guy there who knew what I liked.”

A practicing Buddhist, Erlandson says one of his solutions — to preserve his own personal and musical integrity — is to “stop everything” and take time to reflect and assess. It won’t save the music business, but it may preserve his soul, he says.

For his part, Bennett realized he’d had enough. “I decided I didn’t want to be part of the problem. So I stopped working with bands that didn’t care.” He also hardened his own sense of professional integrity. “At the end of the day, the engineers have an obligation to create great work beyond what society demands.” He currently helps run LMU’s music studios, which allows him to both make a living and educate students on the importance of listening deeply. The interest in predigital analog equipment and the revival of vinyl records feels like a brewing counterculture movement, he says.

Mitchell misses much about the old world, including television shows like “American Bandstand” and “Soul Train” that offered a racially complex mix of artists. But she doesn’t despair completely. “The bright spot is that you’ve got so many folks out there wanting to make music,” she says. “I like the diversity of that. Music is still important.”

Scott Timberg is a writer and editor in Los Angeles. His book “Culture Crash: The Killing of the Creative Class” was published in January 2015. Timberg worked as a Los Angeles Times staff writer for six years, and his work has appeared in The New York Times, Salon and elsewhere. Timberg also has taught writing and journalism courses at LMU as an adjunct professor. His blog is called CultureCrash. Follow him on Twitter @TheMisreadCity.

Sidebar: Streams of Music

By Aaron Smith

Did you purchase a single album (digital or physical) last year? Did you download four songs? If you did, you bought more than the average American. All told, album sales fell 11 percent to 250 million and digital songs decreased 12 percent to 1.26 billion in 2014. If it sounds like a slow fade for the music business, it can also be heard as a change of tune. Music isn’t dying, it’s streaming.

The music consumer is turning to streaming and web radio services like Spotify and Pandora, where they can access unlimited music for a monthly fee of about $10 (or free with ads). Last year, 164 billion songs were streamed — that’s up 54 percent over 2013, amounting to half a billion per day or more than 500 songs per person, according to Nielsen SoundScan. And the trend is only growing.

Spotify now claims more than 60 million users worldwide, including 15 million paying subscribers. Apple, music’s biggest retailer, will launch a similar service this year while maintaining its iTunes Radio service. Pandora has more than 81 million U.S. users — up 7 percent from 2013 — who rely on the company’s algorithms to choose music for them. And YouTube is beta-testing its own subscription service alongside its enormous library of videos, which effectively function as the world’s largest free-music option. In all, there are now close to 100 streaming providers.

Not surprisingly, music labels and many artists, high-profile and otherwise, are not happy with the new terms of engagement. How can they survive with all this music available for less than the price of a single album per month — or, worse, for free?

Well, it turns out the average American never spent $10 a month on music during the industry’s glory days, long before streaming. And Apple has reported that its best iTunes buyers spend about $60 a year on downloads — $5 a month.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek defended the streaming model in a recent blog post: Piracy doesn’t pay artists a penny… Spotify has paid more than two billion dollars to labels, publishers and … songwriters and recording artists. And that’s two billion dollars’ worth of listening that would have happened with zero or little compensation to artists and songwriters through piracy or practically equivalent services.”

While the big labels, never known as an artist’s best friend, are struggling to make a compelling counterargument to the consumer, many artists maintain the current pay model is unsustainable. But the fact is, our listening habits have changed. And music streaming, for better or worse, is now mainstream.

Aaron Smith is a Los Angeles-based writer covering education, entertainment and technology. He is a frequent contributor to LMU Magazine.

This article appeared in the summer 2015 (Vol. 5, No. 2) issue of LMU Magazine.