According to the immortals of Spain’s Real Academia Española, we are angelinos. The royal academy’s emblem, appropriately, is a refining crucible, wreathed in fire, with the motto Limpia, fija y da esplendor. The RAE has been purging, pinning down and burnishing Spanish since 1713. Its language fixes became royal decrees in 1844. The numeraries of the academy continue more democratically today to wrangle into order the grammar, spelling and vocabulary of Spanish speakers. We became angelinos because of basketball. When the Lakers signed the Catalán forward Pau Gasol in 2008, Spain’s sports writers needed a ruling on what to call Los Angeles fans. It was unclear if they should be angelinos, angeleños, angelopolitanos or another gentilicio (which in Spanish denotes a people). The rapid response unit of the royal academy — the Fundación del Español Urgente (Foundation for Emerging Spanish) — picked angelino, a gentilicio in dictionaries and already used by Spanish-speaking residents of Los Angeles.

American English doesn’t have an academy for fixing the language, but it did have H. L. Mencken — journalist, curmudgeon and scholar of American speech. Mencken was passionately committed to American English in all its ways and varieties (called descriptivism by linguists, in contrast to the prescriptivism of the RAE and other language conservatives). In 1936, he mused in The New Yorker on the words commonly used to name an American people:

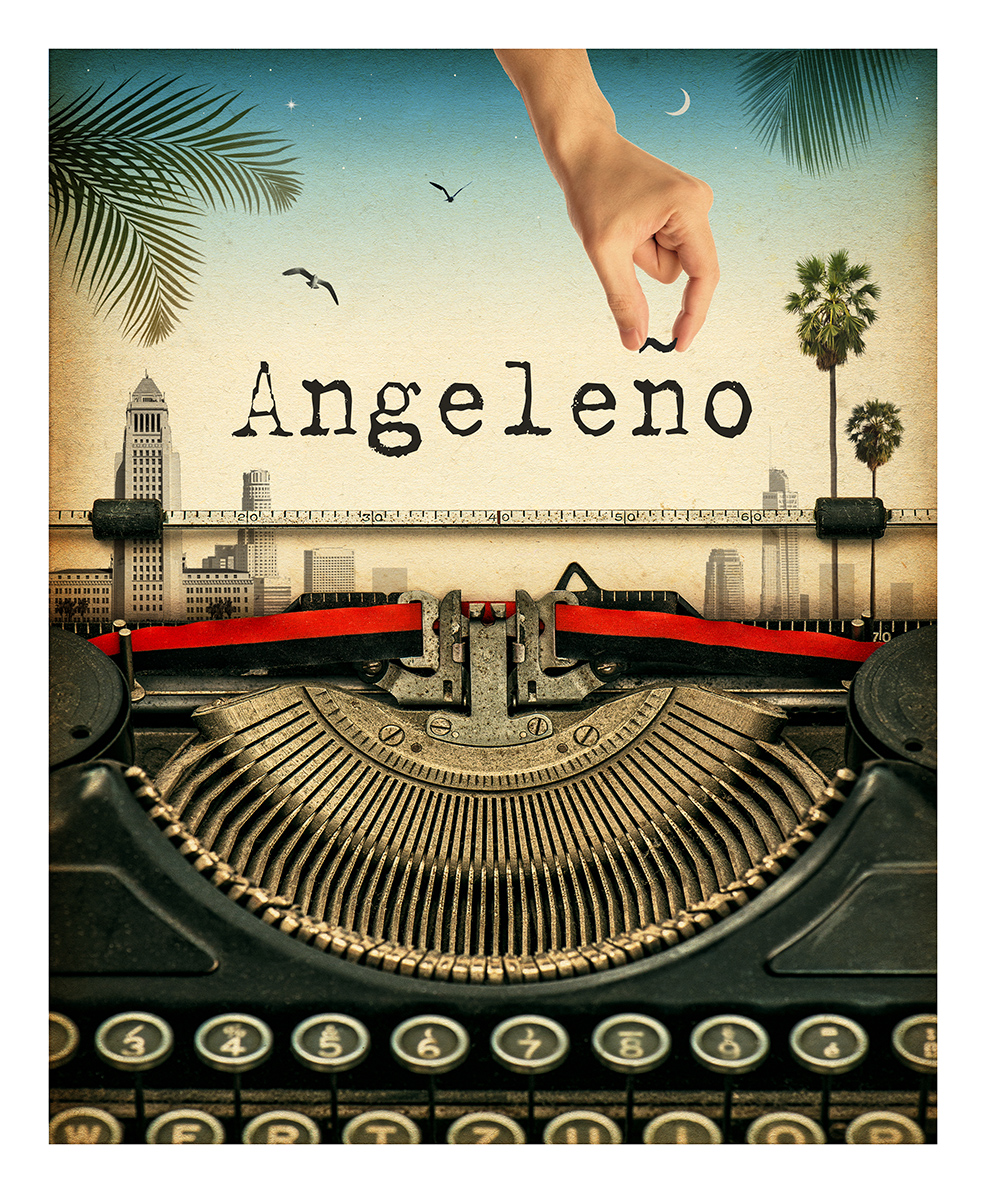

“The citizen of New York calls himself a New Yorker, the citizen of Chicago calls himself a Chicagoan, the citizen of Buffalo calls himself a Buffalonian, the citizen of Seattle calls himself a Seattleite, and the citizen of Los Angeles calls himself an Angeleño. … In Los Angeles, of course, Angeleño is seldom used by the great masses of Bible students and hopeful Utopians, most of whom think and speak of themselves not as citizens of the place at all but as Iowans, Nebraskans, North and South Dakotans, and so on. But the local newspapers like to show off Angeleño, though they always forget the tilde.”

Mencken hated Los Angeles for its provincialism, which may explain in part why he favored Angeleño, the least common, least Iowan and most musical word to bind a heedless people to their place. He presumed that the tilde in Angeleño was an accent mark that careless Anglo typesetters forgot. It isn’t. The unfamiliar ñ — eñe (pronounced enyé) — has been a separate letter in the Spanish alphabet since the 18th century. (Think of the “nyon” sound in cañon, although that’s not quite it either.) Angeleño to Mencken may have sounded something like ăn′-hǝ-lǝnyō or perhaps ăn′-hǝ-lānyō, with stress on the first syllable, which sounded more like awn and less like ann.

He presumed that the tilde in angeleño was an accent mark that careless Anglo typesetters forgot. It isn’t.

Angeleño wasn’t the word residents of Los Angeles would have seen in the Los Angeles Times in 1936. Mencken was right that the most used Los Angeles demonym (the technical term for a place-based name) was Angeleno, without the eñe. The Times spelled it that way in more than 700 articles in 1936 alone (and at least 10,000 times between 1930 and 1950). Angeleno — usually pronounced ăn′-jǝ-lē′-nō — stresses the first and third syllables and sounds like nothing in Spanish.

In picking Angeleño, Mencken, perhaps unthinking, had fallen into the prescriptivist trap. When an expert makes a definitive choice — and Mencken was a language expert — it’s understood to be the “right way” to say something. But the people of Los Angeles didn’t have the perfect word for themselves, even before the diaspora of flat-voweled Midwesterners arrived in the 1920s. We still don’t have one word that holds us all.

Disappearing Ñ

A 2015 report to the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission, in a filing to give historical status to a Victorian-era house, described its location as Angelino Heights, Angeleno Heights and Angeleño Heights almost interchangeably. Naming the heights — the city’s first suburb in 1886 — overlays a sequence of demonyms on the landscape of Los Angeles and threads them through the city’s history.

The maps that parceled out lots on a ridge overlooking downtown were headed with the title Angeleño Heights. That brand name became Angeleno Heights in the advertising copy of the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Herald, probably because the decorative typefaces used by compositors for real estate ads lacked the eñe character. The Herald did use Angeleño Heights in other contexts after 1886, but not exclusively. The Times used Angeleno Heights in classified ads and news stories, but a very few listings and location references used Angeleño Heights instead.

The Birdseye View Publishing Co. rendered virtually every building in Los Angeles on a 1909 aerial perspective map. A single block of houses on a ridge along Kensington Road, isolated among empty fields, is labeled Angeleño Heights.

Angeleño Heights completely disappeared sometime before World War I. Angelino Heights rarely appeared, except in a few house-for-sale ads, probably typeset that way when the seller called in the ad. It’s an easy error for an English speaker to make when spelling by ear. For English-only speakers, both Angelino and Angeleno can sound the same. Anecdotal accounts suggest that spelling by ear led city planners in the 1950s to anglicize the neighborhood’s name as Angelino Heights, as if they were modern-day Noah Websters reforming an alien word to conform to the speech of the city’s Anglo ascendency.

Highway directional signs continued to point to Angelino Heights until 2008, when Los Angeles City Councilman Ed Reyes had them replaced, correcting the signs back to the first, eñe-less error. Eventually a truce was called. At Bellevue Avenue and East Edgeware Road are two signs that spell out the neighborhood differently: Angeleno Heights is on the highway sign; the historic marker uses Angelino Heights.

Angeleño, Angeleno, Angelino

The 130-year drift from Angeleño to Angeleno to Angelino back to Angeleno parallels the uncertainty that lingers in our name for ourselves. In 1850, when the Mexican ciudad de los Ángeles abruptly became the American city of Los Angeles, its tiny Anglophone population was necessarily bilingual in borderlands Spanish. Court proceedings, city ordinances and city council meetings were in both English and Spanish (and sometimes only in Spanish). What the city’s new Americans called themselves isn’t clear. It may even have been angeleño. The eñe was still in the type fonts of printers. The Star/La Estrella — the city’s bilingual newspaper — accurately characterized travelers from Sonora as Sonoreños in 1853. But the paper apparently had no collective name for Los Angeles residents, identifying them as Americans, Californians and Mexicans in the English language columns and as americanos, californios and mejicanos/mexicanos on its Spanish pages. El Clamor Publico — the city’s Spanish language newspaper in the 1850s — did the same.

Angeleño is already in the reality of Los Angeles.

It wasn’t until January 1878 that the Los Angeles Herald listed the names of residents who had recently traveled to San Francisco as Los Angeleños. By 1880, the Herald had clipped this to Angeleños, a spelling the paper continued to use intermittently with Angelenos through early 1895. The Herald then carried on without an eñe until the paper merged with the Los Angeles Evening Express in 1921. The Los Angeles Times was equally inconsistent. In 1882, less than a year after its first edition, the paper was regularly referring to Angeleños collectively. Angeleños (sometimes with “Los”) appeared in news and society columns through mid-1910, a linguistic puzzle for the growing number of residents who had never heard their demonym correctly spoken in Spanish. But Los Angeles writers had heard something.

In 1888, Walter Lindley and J. P. Widney made reference to Angeleños in their popular guidebook to Southern California, as did California booster Charles Lummis in Out West magazine in the late 1890s. T. Corry Conner’s city guide in 1902 and J. M. Guinn’s history of California in 1907 both used Angeleño to name Los Angeles residents. Harris Newmark — who had arrived in Los Angeles in 1853 and who had learned Spanish before he learned English — calls fellow residents Angeleños throughout his 1916 memoir of the early days of American Los Angeles. There were other instances in travel books and real estate promotions written by anonymous boosters. At the turn of the 20th century, the eñe in Angeleños lingered at the margins of the city’s self-image, a fading music. But had it ever played?

Orthographic Salsa

In 1948, the Los Angeles Times style guide directed the paper’s copyeditors to reference Angeleno/Angelenos exclusively. Angelino/Angelinos made it into other papers, spelled in imitation of the sound that Midwest transplants gave to the last syllable of loss an´-je-leeze (when they didn’t pronounce Los Angeles as loss-sang-liss). From the Times’ style guide, Angeleno/Angelenos made it into dictionaries: in the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (which gave Angeleño as an alternative), in the third unabridged Merriam-Webster Dictionary (which offered Angelino as an alternative), and in the current American Heritage Dictionary (without any alternate spelling).

Dictionaries that provide word origins point to angeleño and the Spanish eño morpheme as the source from which American English Angeleno was derived. It makes a neat evolutionary tree. Angeleño (hard for English-only speakers to guess a pronunciation) begets Angeleno (easier, but unclear about the value of the second e), which becomes the mid-century’s Angelino (finally pinning down that value). Except the Angeleño root may be conjectural. The Oxford English Dictionary dates its first appearance to 1888 in the Lindley and Widney guidebook. The appearance of Angeleño in the Los Angeles Herald in 1878 pushes back the word’s first use in print by a decade (and perhaps a bit further in speech). But 1878 is at least a decade after the city ceased to be casually bilingual. For Robert D. Angus, writing in California Linguistic Notes, the Angeleño origin story is unlikely. The word “appears to be a self-conscious and intentional (but erroneous) emulation of a Spanish looking and sounding form, a kind of fashionable hypercorrection, garnishing an article in a trendy publication like a dab of orthographic salsa.” Despite the appearance of Angeleño/Angeleños in contemporary publications in Latin America (and even in the English language newspaper published in the Filipino city of Angeles), each fresh occurrence might be another instance of spreading the orthographic salsa very thin. The pull of American English, Angus thought, would naturally correct the problem, and we would properly be Los Angeleans one day.

Who Do You Say We Are?

Sieve books in English published since 1950 for the names that the people of Los Angeles have been given and Angelenos tops the alternatives: angelinos, angeleños and Angeleans. That doesn’t make Angeleno the right (prescriptionist) way to identify each of us but only the provisional and typical (descriptionist) way. No more right is angelino (with an aspirated g that breathes into the following e), despite the royal academy’s decision to fix our gentilicio. Nor is an anglicized Angeleño more correct, despite my own attempts (and of some in the Latinx community) to foster it back into use. Angeleño might be a linguistic myth, a reminder of Anglo nostalgia for the fantasy romance of Spanish colonial Los Angeles, but that it may be a myth is inconsequential. Angeleño is already in the reality of Los Angeles. As María del Mar Azcona Montoliú wrote, if you “remove the myth in the service of a myth of objectivity,” then “reality is made less real.”

Although we are no longer Mencken’s tribes of “Iowans, Nebraskans, North and South Dakotans, and so on,” a worse alternative for the future would be two permanently divergent language streams, their Spanish and English histories separated although they share the same place. A Latinx resident of Boyle Heights could choose to be exclusively an angelino, the Anglo Westsider would always be an Angeleno, and neither angelinos nor Angelenos would know the full music of the other’s voice, depriving both of the hybridizing mestizaje of Los Angeles speech. They would never experience some of the strangeness that Jesuit philosopher Michel de Certeau thought was necessary to make the everyday a bit more difficult in order to make it more truly felt. They would not know the many stories of their place and end by not knowing their place at all. “Through stories about places,” de Certeau wrote, “they become habitable. … One must awaken the stories that sleep in the streets and that sometimes lie within a simple name.”

Los Angeles existed first in the mouth. It was spoken before it was. It was inhabited by words before it was lived in by us. In the process, Los Angeles has gathered many names. All of them have entered into language and the imagination and thus into history. Angelino, Angeleno, and Angeleño (even Angelean) are part of who we are, part of our sense of self and place. We are all those names.

D.J. Waldie is a cultural historian, memoirist and essayist. His most recent publications are “Ruscha, LA, and a Sense of Place in the West” and “A River Still Runs Through It,” a social history of the Los Angeles River. He is a recipient of the California Book Award, the Whiting Writers Award, and the Dale Prize for Urban and Regional Planning. Follow him @DJWaldie.