LMU basketball will always be linked to transfers. Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble, the two most celebrated players in school history, came from USC. Few remember they played one season for the Trojans before winding their way to Westchester in the wake of a coaching change.

More than three decades later, as Coach Stan Johnson scans the roster of a team trying to recapture the glory days their forebears enjoyed when Kimble — fortified by the memory of his recently deceased teammate — carried the Lions on a romantic run to the 1990 NCAA tournament’s Elite Eight, the coach sees one transfer after another.

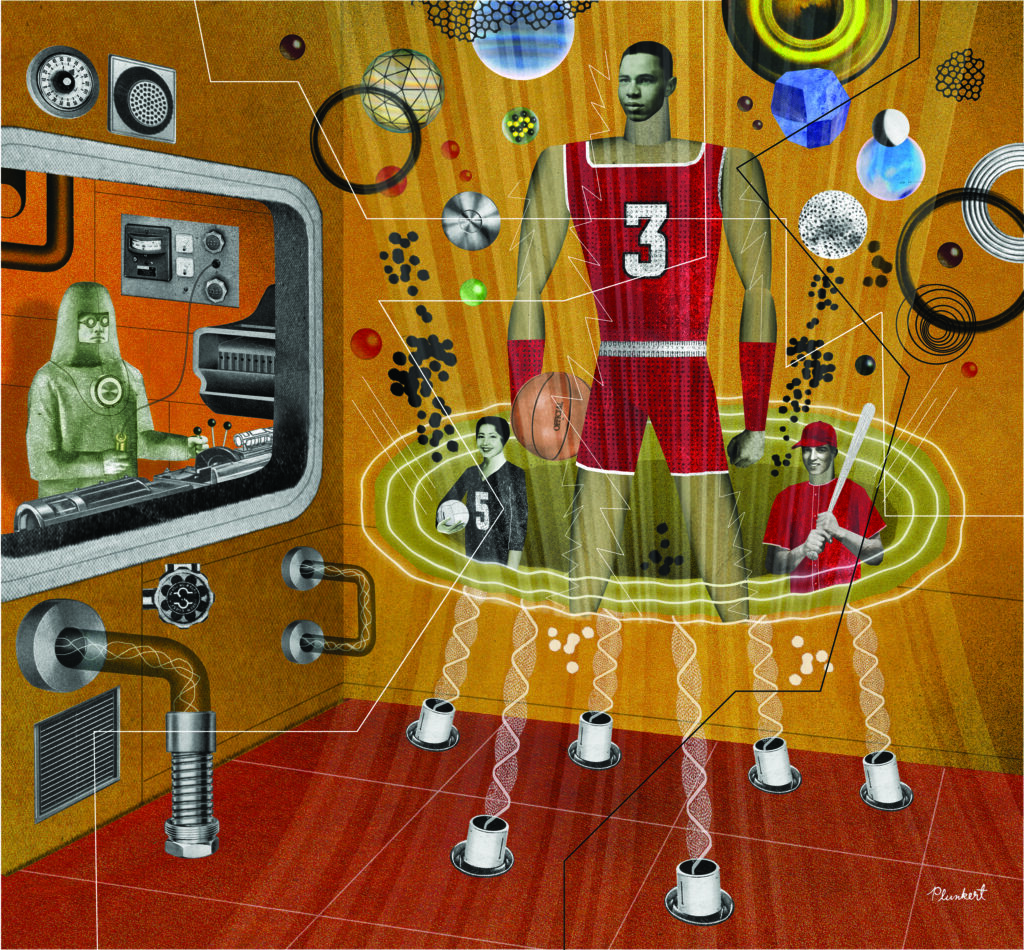

Dominick Harris came from Gonzaga. Noah Taitz came from Stanford. Lars Thiemann came from Cal. Rick Issanza came from Oklahoma. Alex Merkviladze came from Cal State Northridge. Justin Wright came from North Carolina Central. Michael Graham came from Elon. Two others have transferred multiple times. Will Johnston came from the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, after having previously played for South Georgia Tech. Justice Hill is starting his fourth school after stints at Louisiana State, Murray State, and Salt Lake Community College.

That’s a lot of movement. Nine of LMU’s 13 scholarship players — a whopping 69.2% — started their college careers elsewhere.

“They’re from all different spaces and levels,” Johnson says. “It doesn’t mean that a guy who comes from a higher level is a better player, either.”

One only needs to go back to last season to find an example. Former LMU guard Cam Shelton, who came from Northern Arizona and the Big Sky Conference, led the West Coast Conference by averaging 21.4 points during his final college season, including 27 during an epic road upset of Gonzaga that ended the Bulldogs’ 75-game home winning streak.

NCAA data shows that Lions basketball might be an outlier in terms of its heavy reliance on the transfer portal that opened in the fall of 2018, though additional exceptions exist in other sports on the LMU campus and throughout Southern California. Seven starters on the LMU women’s beach volleyball team that finished No. 3 in the country in 2021 were transfers.

“At the root of it for every school, it’s a great opportunity to address needs,” LMU Athletic Director Craig Pintens says. “If done right, it can really provide another opportunity for somebody.”

Or, in many cases, a good chunk of the roster.

USC’s football team went from a 4-8 laughingstock in 2021 to the doorstep of the College Football Playoff in 2022 after reloading with quarterback Caleb Williams, receiver Jordan Addison and a host of other talented transfers. UCLA football has relied so heavily on the portal as part of a recent upward trajectory that one of its own social media staffers referred to the program on Twitter as “Transfer U,” never mind that the designation made coach Chip Kelly cringe and call it a mistake.

“Where can I get better and win and give myself a chance?”

While some numbers might paint a different picture — men’s basketball transfers actually declined from 1,198 in 2021 to 1,123 in 2022 — Johnson contends that the portal will forever change the way his program operates, equating it to the constant movement seen in NBA free agency and the G League.

“The days in college basketball where you said, ‘Hey, look at our team — in two years we could be really good’ or ‘This is our core group that we can grow,’ that’s over,” Johnson says. “It is absolutely a one-year, build-your-team-for-that-year’ [operation] and then figure it out.”

This might be an opportune moment to point out that some NCAA officials commence a heavy eye roll whenever they hear anything related to transfers pinned on the transfer portal, noting that it’s essentially a compliance office construct that did not suddenly make it possible to move from one school to another. Transferring has long been permissible under NCAA rules, it’s just that now schools can no longer block communication between prospective coaches and athletes.

Athletes who wish to explore the possibility of transferring — while also retaining the option to remain at their own school, should their coach hold their scholarship — ask the compliance office on their campus to enter them into the portal. Coaches use that database to search for athletes who might fulfill their roster needs.

It’s impossible to know if the advent of the portal accelerated athlete movement because there was no data surrounding transfers prior to its inception. However, there was a 17.5% increase in Division I athletes transferring to another NCAA school at any level between the 10,129 who entered in 2021 (classified as from Aug. 1, 2020 to July 31, 2021) and the 11,902 who entered in 2022 (classified as from Aug. 1, 2021 to July 31, 2022).

Factors that contributed to that jump include the extra year of eligibility granted in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the April 2021 elimination of a rule that required some transfers to sit out a year at their new school. According to the NCAA, in many sports nearly a third of those who transferred to other member institutions in 2021 and 2022 were graduate transfers capitalizing on COVID-19 eligibility extensions.

“At that time, our student-athletes were granted an extra season of competition,” says Susan Peal, the director of governance at the NCAA who oversees the national letter of intent program and the transfer portal. “So those student-athletes who may have been moving on because they have their degree — they don’t have any eligibility remaining, typically they would have moved on — now they’re staying or they’re saying, ‘Hey, I have one season, I have two seasons remaining, I’m going to go somewhere else’ or ‘I already graduated and now I have this bonus season, I’m going to go to grad school somewhere else.’ So it’s really difficult, until we get through this COVID-19 [eligibility], which will all play out in another year or so, to make any comparisons.”

What about the widespread coaches’ lament that many athletes who enter the portal never find a new home on the other side? While it’s true that 43% of the athletes who entered the portal in 2021 and 2022 have not landed at another NCAA school, Peal noted that many of those athletes are either still exploring transfer options, enrolled at a non-NCAA school or left their sport to pursue other options. (The NCAA did not count those who withdrew from the portal and remained at their current school in its figures.)

“We can only track them if they’re going to another NCAA institution,” Peal says, “but a lot of those student-athletes end up going to a two-year college and they have great success stories. A lot of them go to non-NCAA institutions or they decide ‘I’m no longer going to be a student-athlete, I’m going to stay at my school but I’m not going to be a student-athlete’ or ‘I’m going to go to another school and be a student and maybe have a great academic career.’ So when people say they go into the transfer portal and they just live there and don’t emerge anywhere, that’s actually not true.”

During the early days of the portal, some longtime college sports observers such as basketball analyst Dick Vitale voiced concerns about mid-major schools such as LMU turning into a feeder system for bluebloods such as Kentucky and Duke. The thinking was that a player would blossom at the smaller school for a couple of years before being swooped up by a more high-profile program.

In reality, the movement has often gone the other way. Among the Division I men’s basketball transfers over the last two years, 23% have moved on to Division II schools and 1% have dropped all the way to Division III. Many have gone from Power Five programs to mid-majors. After languishing on the bench for one season at Illinois, guard Brandin Podziemski averaged 19.9 points last season at Santa Clara and was named WCC Co-Player of the Year.

LMU snagged Dominick Harris from Gonzaga, the preeminent program in the WCC. After logging just 57 minutes last season with the Bulldogs, Harris was seeking what Johnson described as a “clean slate and a refresh” while playing closer to his Murrieta home. Coaches have found that players’ priorities tend to change as they mature.

“Some of these guys that you talked to as high school kids, what was important then is not important now,” Johnson says. “It’s not about what’s the biggest arena, who’s got the biggest locker rooms. I think they’re seeing, hey, my career is dwindling and I haven’t played, I want to play. Where can I play? Where can I get better and win and give myself a chance?”

One factor that Johnson has found increasing in importance as he pursues transfers is name, image, and likeness opportunities (NIL). LMU’s recent success in creating a more robust program for its athletes in the NIL space has enabled it to land more attractive transfers.

“I don’t use NIL to win a guy over; I use it to close,” Johnson says. “If a kid wants to come to LMU just because it’s going to be where he’s going to get the most money, I don’t want that kid. That being said, though, in a recruiting war as we’ve gone down the line and identified if it’s a fit for us and a fit for the kid, it’s been a huge reason we’ve been able to put together the kind of roster we have this year. We were able to beat some people out where in the past we wouldn’t have been able to if we didn’t have those resources.”

LMU women’s beach volleyball coach John Mayer, who estimates his roster is sprinkled with five or six transfers a year, said one major selling point of the portal for coaches is the reliability of players who have already shown what they’re capable of doing in college.

“When you’re recruiting high school players, it’s a game of predictions that you’re trying to guess how good they’ll be in two years, especially at a time when they’re still developing, so you’re playing a guessing game,” Mayer says. “With a transfer, you have evidence of their success at the college level, so you’re able to get more data and make better decisions.”

Not always. Johnson noted how many players seeking a new home in basketball do so because they barely played at their previous stop. That leaves his staff to project based on potential.

“Some of these guys in the portal don’t have numbers or they didn’t play; it doesn’t mean they’re not good, but how do you evaluate that?” Johnson says. “So you have to have a system in place to not just go off numbers; there’s guys with great numbers and it doesn’t mean when they transfer they’re going to produce, so there’s a lot of things you have to have in place to limit the amount of mistakes you make.”

It’s a risk Johnson is more than willing to take as he continues to build his program. His plan is to bring in one or two high school players per year and fill the balance of open roster spots through the portal.

“As we move forward that’s what it’s going to look like for us,” says Johnson, who is entering his fourth season on campus. “It’s going to be transfers, hopefully transfers that have multiple years.”

After so much waiting for another special March memory, it might make the difference in bringing some welcome madness back to Gersten Pavilion.

Ben Bolch has been a sportswriter for the Los Angeles Times since 1999. He covers the UCLA basketball beat and is the author of “100 Things UCLA Fans Should Know & Do Before they Die.” His “Moneyball” appeared in the fall 2022 (Vol. 11, No. 1) edition of LMU Magazine. Bolch also appeared on LMU Magazine’s Off Press podcast. Follow him @latbbolch.