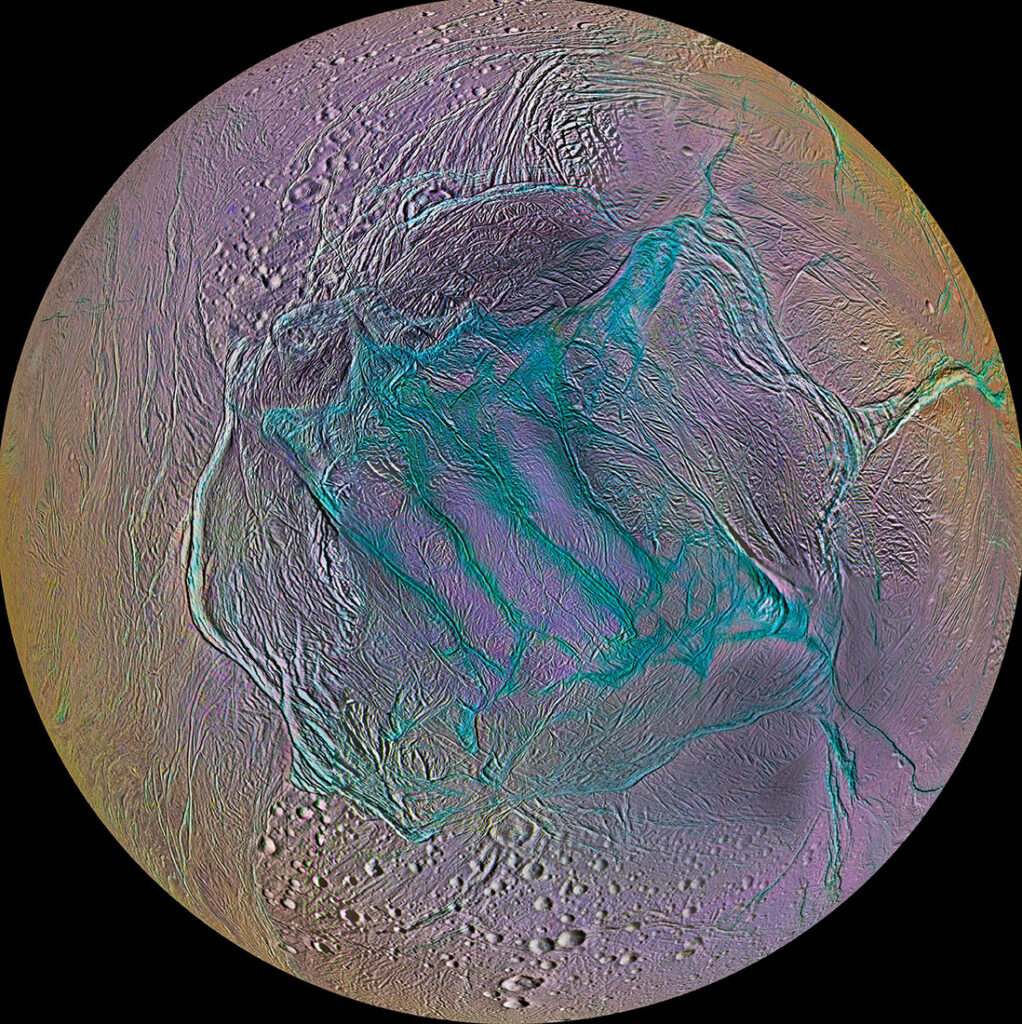

More than 790 million miles from Earth, Saturn’s moon Enceladus resembles a white pearl marble, its bright, icy glaze making it the most reflective object in the solar system.

It is one of the more curious celestial bodies, enough to keep Emily Hawkins awake at night pondering its mysteries. Hawkins, who teaches physics in the LMU Frank R. Seaver College of Science and Engineering, is particularly interested in the watery moon’s implications for life beyond Earth. Unlike most water-bearing interplanetary bodies, Enceladus blasts water vapor 800 mph on average into the atmosphere, giving scientists precious data, and, moreover, evidence that life might exist beyond earthly confines.

“It’s just so enthralling to me,” Hawkins says. “Anywhere there’s water in the solar system, there could be life. Without water, you cannot generate the mechanisms needed to start a chain of chemical reactions that will generate something like a microorganism. It has huge implications for helping us to better understand our place in the solar system, the history of the solar system, and how planets formed. We have some understanding, but not fully.”

“Anywhere there’s water in the solar system, there could be life.”

— Emily Hawkins

While some planetary physicists study impact cratering processes or planetary system formation, Hawkins has focused on “the beauty of fluids.” Besides Enceladus, she’s also focusing on Europa, a moon of Jupiter which, like Enceladus, has a water-ice crust.

Growing up in Petaluma, California, Hawkins excelled in English and writing. She was less strong in math and science. Or so her teachers told her. “I carried that with me through the eighth grade,” Hawkins says. But she knew that she possessed a buried love for science. It was in high school that teachers “ignited” her scientific yen and encouraged her explorations into the mysteries of the universe. Friends were similarly encouraging.

“I was looking for a way to feel really engaged,” she says, “and physics brought a new level of feeling for me.”

“I might be a late bloomer, more than other scientists, who have these narratives of being interested in the stars and what’s beyond Earth since they were really little,” Hawkins adds. “In college, I was very tentative, hesitant even, to start as a physics major. I didn’t know any girls who were going to try to do physics in college.”

As a result, she declared psychology as her major as an undergraduate. The cosmos, however, exerted its incontrovertible pull. She switched her major to physics, despite her nervousness.

“I felt like I didn’t belong in the room to learn these things,” Hawkins says.

She’d go on to earn her master’s and doctoral degrees in geophysics and space physics before arriving at LMU. Now she’s building a device to study the ocean dynamics of Enceladus and Europa. She’s collaborating with members of NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, which is scheduled to launch in October 2024. That mission will help analyze the potential for life beyond Earth.

By extension, her work attempts to divine the conditions under which life can generate on its own. It’s not fully understood how humans came to be, “so the more we can study other analogous systems, the better we can understand that,” Hawkins says.

As an astrophysicist, she invariably is asked the same weighty query: Is there life beyond Earth? Hawkins is both a pragmatist and scientist in her response.

“I really don’t know,” she says. “Based on the size of the universe and probability, it seems impossible that Earth is the only body in the universe that would contain microorganisms or greater-level life.”

They are the questions to lose sleep by.

Andrew Faught is a freelance writer based in Fresno, Calif. He has covered politics, education, and human interest stories for newspapers in California and Arizona. He has also written for Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, Smith College magazine, and Occidental magazine. Faught previously wrote an article about the research of Demian Willette, professor of biology, for LMU Magazine.