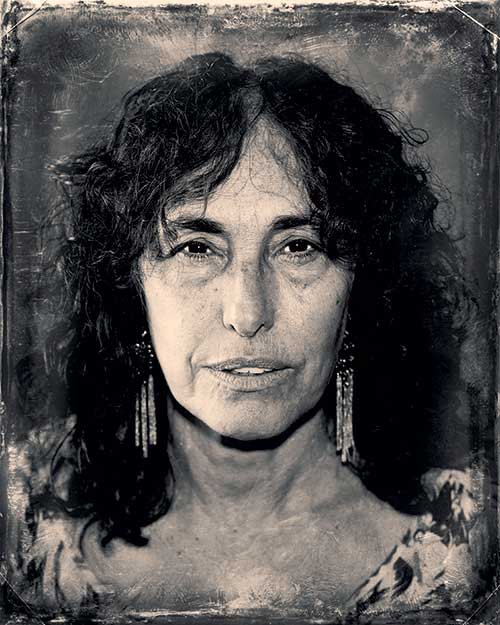

In March 1976, the Argentine military seized control of the country’s government, ruling for seven years. Some 30,000 people were “disappeared” — secretly arrested, tortured in unknown locations and eventually killed — by the regime. Alicia Partnoy, professor of modern languages, was among the few survivors. She spent almost three years in prison before being released. This fall, LMU launched Casa Argentina, a study abroad program in Córdoba that Partnoy helped plan. Editor Joseph Wakelee-Lynch spoke with Partnoy about the coup and its aftermath, her detention and LMU’s Casa project.

Were you politically active when the coup took place?

I was at university where I was a student body representative. I was voted in as a representative because I was a very good student but not very politicized. When the coup took place, I decided to get more involved. That’s a little paradoxical, because you would think this is a moment when you should hide.

There were 10 months between the coup and your arrest. Were you aware of the danger you were in during that time?

I was very aware of the danger. I was disseminating information about the people who had been arrested before me and my husband. The moment they came to get me, we were printing leaflets about a woman who had been kidnapped, tortured, and thrown into a ditch and left for dead. She survived, and we told her story in our leaflet.

Do you have any idea why you remained free for 10 months and weren’t arrested sooner?

Our work was clandestine, and we had a network that was not open. I didn’t go to school, because they checked every student who walked into buildings and checked all of our belongings. People in our group sometimes would go away, and it was hard to keep track of whether they were arrested or not. Apparently, somebody was arrested, and that person gave information about where I was. That’s how they got me.

Did you ever consider fleeing Argentina?

No. We had the means: I came from an upper middle class family. But my husband and I refused to flee. My daughter was little, and I thought I don’t want her to grow up in a society under a dictatorship. She was 18 months old when we were arrested. She was left behind when the soldiers took us, and my family rescued her and raised her for the three years we were in prison. My daughter is now 38 years old. Now she will testify via Skype in trials in my hometown for crimes committed then.

Many people who were disappeared were killed in detention, while others were not. Why were some people allowed to live or even be released and reappear?

We were hostages. Disappearing people is a way of taking hostages, and it was useful to the military to have hostages. Sometimes it was useful to them to have us reappear, because it indicated that the military wasn’t killing indiscriminately. Also, the effect on relatives of people disappearing was strong in terms of paralyzing the population. First, they didn’t want people to mourn the deaths because that would generate public funerals, public outcry and international attention. Disappearing people also caused guilt in loved ones. After I was released, I went to see the mother of my friend, Mary, who was arrested and killed. She asked me, “What did your mother do that I didn’t? How is it you reappeared and Mary didn’t?” The effect is that guilt for the deaths is reversed from the military to the relatives, who think they are responsible. Disappearing people also paralyzed the relatives. For example, my parents were very active searching for me and my husband and denouncing the crime. But they didn’t present a writ of habeas corpus because they thought it could be counterproductive. Relatives didn’t know what would help.

In Argentina, do some people live with a stigma for having collaborated with the military?

Society is still divided. The military had a lot of time to persuade the population that what they did was right.

Trials have been taking place in Argentina since 1985 and continue even now. Is it possible to achieve justice, or is knowing the truth more important than trying to bring about justice?

I think justice is the most important thing. We who are victims, we who are survivors, we know the truth. We know what they did. They can come and apologize to us if they want, but I don’t think societies are safe only with the truth. We don’t want somebody who killed somebody just to tell the truth. We want a measure of justice so people can walk the streets safely.

While I testified on the witness stand, the 17 alleged killers were sitting behind me in the second row of the auditorium where I went to university. But behind them were the relatives of my friends who died and their children and other human rights activists.

In December 2011, you returned to Argentina to testify against your captors. Did any of them admit what they did?

While I testified on the witness stand, the 17 alleged killers were sitting behind me in the second row of the auditorium where I went to university. But behind them were the relatives of my friends who died and their children and other human rights activists. The defendants refused to speak at the beginning. When they made final statements, many said they were innocent. Some blamed others in their forces. Some were in intelligence work, and they said they were involved in Argentina’s conflict with Chile. Some said, “We were clipping newspaper articles about the war and subversive actions.”

Have you wondered what makes people capable of torture?

There is some fascination with this question: “Why do people torture? Could I be a torturer?” I don’t want to go there. I don’t think it’s relevant. I didn’t know their names. I’m not interested in knowing what was going on in their heads. Personally, I don’t want to create more space in my brain than I need to for those people. In my book, “The Little School,” I can see that the biggest flaw is that those people are like caricatures. But I can’t get into their brains. I don’t know how to do it, and I don’t want to do it.

Some crimes have fallen outside the statute of limitations. But crimes of kidnapping and illegal adoption of children of the disappeared continue to be prosecuted. Why?

With the cases involving the children, there is no statute of limitations because the crime keeps being committed: The children continue to be deprived of their identities. The acknowledgement of that fact was the victory of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, who have been working since 1977 to locate the children who were illegally adopted.

This fall, LMU established a Study Abroad program called Casa Argentina in the City of Córdoba. How are you involved?

President David W. Burcham appointed me to the planning committee, and we visited Córdoba. For me, service is part of teaching, and it was an honor to be involved because the purpose of Casa Argentina is to be of service, walking with the marginalized. We visited the praxis sites where the students would later be learning with the local community. Jennifer Abe, professor of psychology, and Douglas Christie, professor of theological studies, run the program now. They are excellent choices in terms of their commitment and understanding of the project. I’m planning to take one of my own classes one summer to help translate the exhibits and record tours in English at La Perla in Córdoba, which was one of the major concentration camps in Argentina and is now a museum of memory.

Are there a lot of concentration camps that have become museums?

Most of those that were not demolished are being turned into places of memory. The place where I was held, the Little School, in my hometown of Bahía Blanca, was leveled. This past year, a monument to disappeared mothers was placed there.

What do you think about when you imagine taking your students to Argentina in the future?

My struggle for all these years is against alienation: How do I keep my past and my present together inside me? How do I keep myself whole? Many survivors who came to the United States to work as professors hide their personal experience, fearing that it will somewhat render them unobjective in doing their research. I chose not to do that. So going with the delegation to Argentina while planning LMU’s program was a major event for me. I put together my life here in the United States with my life in Argentina. I’m very excited to take my students there, because of the contributions they can make and the ways they can learn. I realize that I can be a text for students in more than one way.